The OASIS EMTC (the

Organization for the Advancement of Structured Information System’s Emergency

Management Technical Committee), has developed a list of “event” terms for use

in alert messaging systems. The creation of the list is an attempt to put some

consistency into an important piece of information found in alert messages –

the subject event.

A subject event justifies why

the message was created in the first place, and it helps the alerting authority

anchor the information contained in the message to a specific time and place

for the message audience. The subject event is central to alert messages that

use the OASIS CAP standard.

The EMTC generated the

“event” terms list in response to concerns expressed by the Global Disaster

Preparedness Center (GDPC), a resource center hosted by the American Red Cross.

The GDPC raised concerns that the varied and free form usage of event terms is

inconsistent in CAP services making it difficult to compare messages from

different originating sources. As consumers of alert messages, they found there

is no quick and definitive way to compare the language and meaning of the event

terms found in various CAP messages.

Understanding this, the EMTC

approach to the “event terms list” (referred to as the “list” going forward in

this document) has been to focus on “how” the list can help when comparing

event terms. The design and management of the list is such that consumers of

CAP messages, looking to compare event terms from different originating

sources, will have a means to do so.

The EMTC also recognizes that

many alerting authorities have their own terms; and that these terms, some long

established, already work well in the communities they serve. Therefore, with

the advent of the list, it is not suggested that alerting authorities change to

using the OASIS event terms as listed, it is only suggested that the

originating CAP systems for those authorities make a reference to the terms.

Essentially, the EMTC defers

to each and every alerting authority their choice of terms as those authorities

have had many years to create a relationship with their audiences. The goal of

this EMTC list is only to facilitate a more interoperable exchange of

information to consuming parties. Interoperability means that consumers, even

those not associated with alerting authority in any way, should also be able to

easily process the information. With the methodology outlined in this

document, it is hoped this objective can be accomplished. The OASIS EMTC is

asking CAP originators and CAP consumers to play a part in making this happen.

Ultimately, OASIS hopes users, like the GDPC, will see the benefits.

CAP is designed as a means to

convey information associated to an event of interest. It does this for the

purposes of alerting audiences to the impacts of that same event.

Identifying an event of

interest starts the process of creating an alert with the event becoming the

subject of the alert message. Subsequently, CAP is then used to house the

pieces of information associated to that alert. Consumers of CAP messages,

those considered partners to the alerting authorities generating alerts, help

disseminate and present that information to the intended final audience.

Before a discussion on

conveying information can be made however, additional background on a variety

of concepts pertaining to alerting information, including the meaning of the

term “event” as it used in CAP, is required.

An event is something that

happens in a given place during an interval of time. It is the recognition of

some activity that is a deviation from the normal state of things. An event

only becomes significant when affected parties observe, or are anticipated to

observe, some known measure of impact. On a very basic level, simply existing

is enough for an event to generate interest. On a more practical level,

authorities, with expertise on the nature of certain hazardous or concerning

events, may classify an event as significant based on the real or anticipated

impacts of the event.

In the case of “Public

Alerting”, alerting authorities determine whether the impacts of an “event of

interest” is concerning enough to issue a formal alert. This is their

responsibility; and they can do this consistently because they have built up a

pre-defined and deterministic cause for alarm based on a known set of

conditions of similar events. In this situation, the alerting authority has

assumed the role of defining the impacts of significance on behalf of the

public audience they serve. An event, based on those measures, becomes the

subject of an alert.

CAP consumers are aware that

some of the pieces of information within a CAP message are optional while some

of the information is required. The <event> element within a CAP message

is a required element. It is the only required element in a CAP message that by

definition is directly associated with the subject event. Unfortunately, this

has resulted in many CAP consumers attempting to rely on the element as a means

of comparing the subject events across messages.

However, the <event>

element is a free form text element meant to communicate with the final

audience and not meant for the automated systems to process and make decisions

on. The only constraint on <event> is that it be in the same language as

indicated by the <language> element of the <info> block - but even

that constraint is not easily confirmed. Therefore, for consumers such as the

GDPC, the ability to rely on this element as currently defined, for uses other

than display purposes, is not always possible.

Consequently, it is

understandable that some believe that the varied use of the <event>

element contradicts the concept of interoperability. One possible solution

might be to have originators standardize use of the <event> element to

some standard list of values to overcome this interoperability problem.

However, it is the opinion of the EMTC, that the <event> element in CAP

should not be re-purposed for this task. The <event> element has been

established as an audience element and should remain as such. The EMTC believes

other existing CAP elements should be employed to facilitate interoperability.

To “type” something is to

declare something (formally, or informally) as sharing similar characteristics

to things that went before it. Three key points to be made when “typing”

something are…

1)

Who is making the

declaration?

2)

How is it

formalized?

3)

What pre-existing

characteristics are actually being “typed”?

CAP makes heavy use of the

concept of “type”, but for things like subject events, thwe EMTC doesn’t

actually define the characteristics. CAP leaves the typing of events up to the

communities that use CAP. Type will figure prominently in the discussions in this

document.

When an event is identified

as a subject event, it is helpful if the alerting authority and audience have

some pre-existing knowledge of the expected impacts of the event. That prior

knowledge comes from associating the subject event to a type of event. When an

alerting authority classifies an event based on a set of conditions of other

similar events, they are effectively categorizing a type of event. All events

that meet that set of conditions are categorized to that type. Knowing what the

impacts for a certain type of event are, assists in communicating the impacts

of any single subject event.

The <event> element, as

defined in CAP, is described as… “the text denoting the type of the subject

event of the alert message”. This means that the authority is not actually

citing the specific subject event in the <event> element, only its type. The

most common way to classify a type of event is by a term given to describing

the environmental conditions associated to the event. For example, a subject

event like “hurricane Katrina”, would have an event type classification of

“hurricane” as hurricane is the term given to events with weather conditions

characteristic of a hurricane.

However, other typing schemes

may work off of other aspects of an event. For example, alerting authorities

may “type” an event based on its duration (short / medium / long), or its

severity (extreme / severe / moderate / etc.), or its scale (EF0 through EF5 as

with tornado events) or use proxy terms such as in color based systems (red /

orange / yellow), etc. The EMTC list is primarily based on the most common

typing classification – an event’s “physical” characteristics – but other

typing terms are present.

An alert is a transmitted “signal”

to heighten attention and/or initiate preparation for action. For

this attention and preparation to be meaningful, a real or anticipated subject event

is necessary. As stated, it is by reference to this subject event that the

alert ties the message found in the alert to a time and place.

For many alerting

authorities, an event, simply by its event type definition, is an alert-able

event. For example, a “dangerous animal” is an alert-able event simply because

of what its event type definition is. For other authorities, the event is only

significant and alert-able when a marked set of environmental conditions define

its type. For example, an authority may declare a “wind” event an alert-able

event based on a certain wind speed level marker. Regardless of how the need

for an alert was determined, the authority went through a subjective analysis

identifying event types. All this so that the subject event for any given alert

message has a type classification that aids in constructing alert messages for

an audience.

Identifying events and event

types is often not enough. Organizing an alert message and using meaningful

terms for communicating hazardous or concerning impacts to an audience is just

as important. This is the social aspect of alerting and this is where the

concept of an alert type arises.

An alert type is usually just

the type of event transposed to also being the type of alert. For example, a

“blizzard event”, of event type “blizzard”, would often lead to a “blizzard

alert” of alert type “blizzard”. Since an alert message requires a subject

event to center the message on, it is natural to make this simple transposition

of event types to alert types. This transposition activity holds true for other

event type schemes as well (i.e. a “Red event” becoming a “Red alert”, etc.).

However, the practice of

setting an alert type for alerting authorities is just as inconsistent around

the world as is setting event types. For example, a “hot dry weather” event,

conducive to the possibility of bush fires, may result in alerts such as

“bushfire emergency” or “red flag warning”. The alert types here are “bushfire”

and “red flag”, two terms not necessarily or immediately understood to mean

similar things – especially across different communities. Secondly, is the

event type considered to be “bushfire” or “dry weather”?

Regardless of the what the

event terms used actually signify, the overall social aspect of alerting has

been established within existing communities that uses those terms.

Furthermore, for this exampled case, it should be pointed out that the alert

terms “emergency” and “warning” are not uncommon variations for the choice of

term for an alert. Nevertheless, the conclusion is that the practice of using

terms for naming events and alerts can vary considerably making comparisons

difficult.

Ultimately, public alerting

is not meaningful if the message is not understood. Regardless of the term

assigned to the event or alert, the social responsibility of an alerting authority

is to effectively communicate the hazards and concerns associated to a subject

event. In each case, representatives of the alerting authorities that chose

these terms felt the chosen term was the correct one for that situation. OASIS

is not claiming any jurisdiction over the choice of terms in public alerting or

in CAP.

Since defining what event

types are alert-able is a “community of users” decision; and since properly

referencing subject events to an event type is an aspect of effective

communication, picking the best term (display label) for known event types

can’t possibly be done centrally by one group. To be successful in such an

exercise, there are a number of additional considerations regarding an event

that all parties need to understand. The list below is not a complete list but

the list does demonstrate various aspects of the larger event term problem.

1)

The same event

can affect different communities differently. For example, a smoke event can

affect one community concerned with Air Quality and Health while at the same

time it can affect another community concerned with Transportation.

2)

The same event

can affect a national community in one way and a local community in other ways.

For example, a forest fire can affect logistical firefighting exercises on a

large scale but cause evacuation activities on a smaller scale.

3)

The same event

may be easy to describe in one language but not another. For example, the term

“AMBER alert” is well known in the English language but its direct translation

may not easily survive into another language.

4)

An event may be

composed of many smaller events and the communication of many smaller events

simultaneously may require the use of a broader term to get the message across.

For example, storm surge, heavy rain, strong winds, coastal flooding,

tornadoes, etc… may all be part of a hurricane event but a message full of

references to the many smaller events may not be effective as they could

overwhelm the audience. However, any of these smaller events occurring on their

own could easily make up the subject event of a separate alert.

5)

An event often

comes with descriptors that authorities have used for many years for alerts

based on a how the subject event was viewed in the past. The use of these

descriptors can create confusion. For example, a “Thunderstorm” event and a

“Severe Thunderstorm” event. “Severe” is one of several allowable CAP values

used by agents to filter CAP alert messages but if the value is set to

“Extreme” and the event is still termed as a “Severe Thunderstorm” confusion

can arise.

6)

An event may be

described differently in cause and effect situations. For example, an

earthquake event that spawns a possible tsunami event may result in different

originators referencing either event type in a CAP message. The alert is

“Tsunami Warning” for an anticipated tsunami event but the cause event was the

“Earthquake” event. Alerting Authorities could focus on one, or the other, or

the combination of the two, as the subject event of the CAP alert message

7)

An event may be

considered a trigger event by an alerting authority causing the authority to issue

an alert focusing on a secondary event that they themselves want to initiate.

For example an “Evacuation Order” that contains a message that talks about the act

of evacuating, and may involve very little discussion to the trigger event that

spawned the order in the first place.

8)

An event may be

described by using a proxy term. For example, “red flag” is a term that can be

used to describe an event where a triggering weather event is underway that is

conducive to a secondary fire event occurring. Much like a tsunami event

prompted by an earthquake event, the possible fire event is prompted by an

existing weather event. However, in this case, the term “red flag” is a proxy

term generalizing the possibility of several fire events.

9)

Two event terms

may have the same core term but use different adjectives to qualify the event,

thus creating two different and independent event types solely based on the

choice of adjective. For example, a “bush fire” and a “chemical fire”. While

related due to the core term “fire”, they are actually quite different event

terms only connected through the broader term “fire”.

10)

An event term may

not even be an event at all. For example, an “air quality” event is an

incomplete definition as air quality is actually a continuous state. It is only

implied that the true event is a “poor air quality” event. The repeated usage

of the term “air quality”, for the purpose of issuing alerts for “poor air

quality”, has led to a subtle training of the audience over time to interpret

“air quality” as “poor air quality” when associated with a public alert.

11)

An event term

choice may be subject to the behaviors and constraints of the presentation

systems in play. For example, the idea of keeping messages short for a

particular presentation medium, or only including a short attention grabbing

<headline>. For example, “highway alert”.

Consequently, for an event

terms list to successfully accommodate all interested parties, users of the

list have to recognize that the EMTC list of terms will be large to accommodate

a variety of interpretations. Any community that contributes new event terms

will likely be adding to an ever-growing list. Luckily, there are ways to

engineer solutions to such problems.

One strategy to help

automated systems that auto-process the delivery of the alert message to the

final audience is to codify values for certain pieces of information in the

message. Coded values, if formatted properly, can alleviate the dimension of

language as an issue to resolve when processing an alert. Applying a code to

each item in a list is desirable for automated systems and systems that deal

across languages.

Codifying event types is also

helpful for applying advanced processing in alerting systems. For example, a

coded value for a pre-defined event type allows consumers to have a pre-defined

response to any alert message identifying to that event type. That response

could be for simple tasks such as routing or filtering or it could be for more

advanced tasks such as creating a unique presentation for a certain type of

event. In CAP, codifying event types is facilitated by originators populating

the <eventCode> element.

A group is a collection of

participants that share a common trait. In the case of XML, a language based

messaging protocol, there are two basic user groups. One group is the final

intended audience (the end clients of the information contained within the XML

message), and the other is the partner group (the agents along the path of

distribution that source the XML for decision making information). Both these

groups are served by the same CAP-XML alert message.

There are elements in the CAP

schema that are intended for one group or the other. For example, many of the

free form elements in the CAP-XML schema are intended for the final audience,

while many of the enumerated elements are intended for agents along the path of

distribution. As stated, the <event> element is free form and conveys an

event type to the final audience. Conversely, the <eventCode> element is

a pre-determined element with managed values, and conveys an event type to

agents along the path, allowing them to set up something specific in advance

such as filtering or routing.

There is one additional

event-based decision-making element in CAP. Unfortunately, like <event>,

it does not come with much guidance on how to use it properly and existing

practices with this element are as varied as the <event> element itself.

Besides, it is a very general element and is not specific enough for consumers

to use for most event comparison purposes. This element is the <category>

element.

Like the <event>

element, the CAP standard defines a <category> element to broadly

categorize subject events referenced in CAP messages. The <category>

element is a required element with a set of pre-defined values for this

element. Automated processing on the consumer side could potentially use

<category> to filter to some sort of subset list of events of interest.

Unfortunately, consumers have to rely on the originators upstream to set the

values appropriately and consistently if interoperability is the goal.

Usually, originators just

include one <category> for the hazardous or concerning event of interest

in a CAP message, and that assignment usually just aligns with the jurisdiction

of the alerting authority. This defeats the purpose of <category>. For

example, an alert issued for a “volcanic ash” event may have a <category>

assignment of only “Health” if a health agency issued the alert, whereas it may

have a <category> assignment of only “Met” if a meteorological agency

issued the alert. The recommended use of <category> is to have multiple

instances of the <category> element present in the CAP message - one

instance for each category that applies. The CAP consumer could then reliably

use a filter to look for the categories that interest them and then just

present the <event> value as is to the intended audience. If an alerting

authority added a new event type to their list of alert-able events, a consumer

could build a system filtered to <category> and not miss any new type of

alert that the authority added.

OASIS is not intending to

promote <category> as a solution to the <event> issue stated in the

outset of this document, but understanding <category> and its traits as

compared to <event>, will help us address the event issue. The two

important traits are re-listed here.

1) <category> allows for multiple

instances of the element in a single CAP message. Therefore, CAP does not

constrain events to being in only one category. The <event> element

however is constrained to one value.

2) <category> is a broad

categorization, not enough to inform on the full nature of the event.

Therefore, consumers can use it to filter alerts only at the broad scale. The

<event> element however can be either broad or narrow as needed for the

audience of interest

These two differences figure

in the methodology to solve the event type comparison issue discussed in this

document.

As mentioned earlier, the

social aspect of alerting is a primary concern for alerting authorities. The

chosen terms used in the message exist for the purposes of communicating effectively

with an audience. However, when inspecting the terms used across various

systems, not surprisingly, a wide range of terms are used. Upon further

inspection, the terms are not just similar terms for the same thing, but terms

that span a range of terms across one or more spectra of terms. This happens

both at the event level and the alert level and even authorities themselves

sometimes have a hard time interpreting one another’s choice of terms.

The following is discussion

on terms across spectrums, which will factor into the decisions made regarding

what event terms may make it into the list.

Terms can be very specific or

very general depending on the information that needs to be conveyed. This is

especially true for public alerting. For example, usually the term used for the

event is often the same term used for the alert (i.e. a “wind” event leading to

a “wind warning”). However, some alerting authorities generalize the type of

alert by using broader terms (i.e. a “wind” event leading to a “weather

warning”).

Furthermore, if a combination

of certain events tends to occur at the same time due to the nature of the

events, broader terms are quite often used as a catch all for the individual

events (i.e. a “wind” event, plus a “rain” event, plus a “storm surge” event

all leading to a “tropical storm” alert). From any one physical location

affected by all the individual events, using “tropical storm” makes sense as a

catch all, but for a segment of the audience affected by only a subset of the

events, such as those on higher ground, should they be subjected to the “storm

surge” aspect of the catch all alert type?

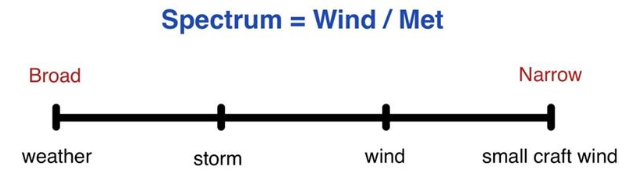

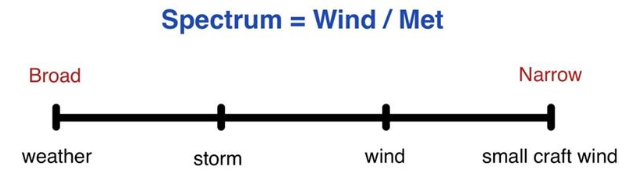

The example below shows a

simple example of “Wind”. There may be many broad to narrow spectrums that

include the term wind, but for this discussion the spectrum that includes the

CAP category “Met” is used.

An authority could elect to

use the broad event term “weather” or the narrow term “small craft wind” when

naming an event. For example, the following combination of CAP elements is

possible

<event> = “weather”

<category> = “Met”

as well as…

<event> = “wind”

<category> = “Met”

or even…

<event> = “small craft wind”

<category> = “Met”

and so on.

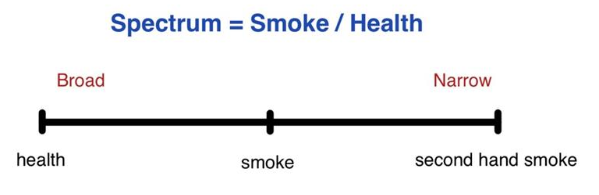

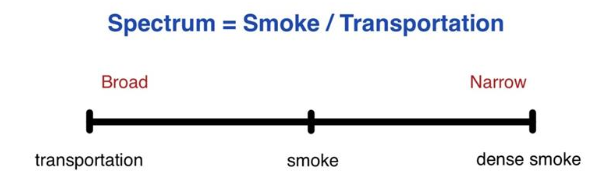

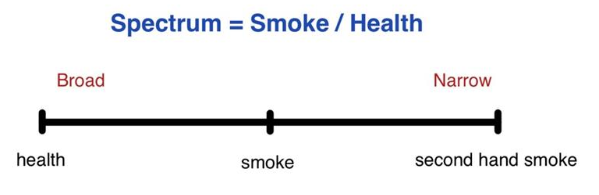

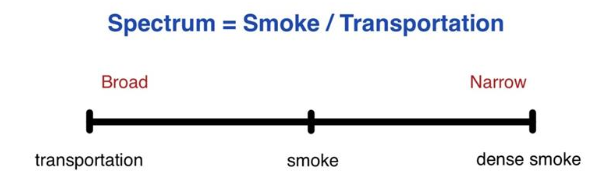

Additionally, reference terms

can appear on more than one broad to narrow spectrum. This is one area where

the <category> discussion above is relevant. For example, using the

“smoke” example from earlier, smoke is a broad term that one can narrow to

either “dense smoke”, affecting Transportation, or “second hand smoke”,

affecting Air Quality and Health.

The impacts of a smoke event

could be associated to two different CAP <category> values, “Health” and

“Transport”. In this case, the broad term would need more context if there is a

consumer that wants to filter for alert messages in just one of either

category.

Furthermore, if the “dense

smoke” is from a chemical fire, and the alerting authority is issuing an alert

for this smoke with both the Health and Transport communities in mind, do they

issue two messages or one? Do they issue a general alert message discussing

both impacts or two alert messages discussing the impacts in each category

separately knowing there is an specific audience for each category? Practices

are many and varied and often go to how the authority conveys the impacts in

the message. OASIS has no jurisdiction over such alerting practices leaving

that up to the authorities themselves, but the practices affect the terms used.

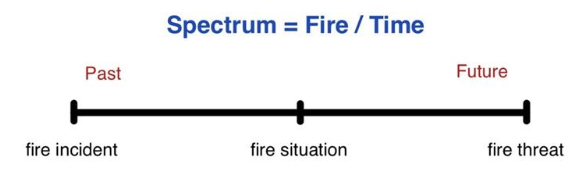

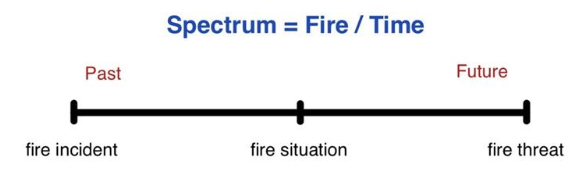

Alerts can be used to alert

audiences to events of interest that have happened, are presently happening, or

are expected to happen in the future. If an event is moving, such as a “storm”,

it can be considered happening now to some and happening in the future to

others. Furthermore, if an event is only anticipated to happen, it may end up

not happening if the conditions leading up to the event change before the event

happens. All this can affect the chosen terms used to describe an event across

the time spectrum.

Consider for a moment a term

like “forest fire”. Since a forest fire is an event by its nature, something

that deviates from the normal condition of no fire, the term “forest fire” is

an acceptable event type term. However, if an authority wants to define forest

fires types for existing forest fires and future forest fires, how is that

accomplished? Terms such as “forest fire situation” or “forest fire threat”

come to mind, along with many others similar terms. When inspecting these

choice of terms however, a sense of timing can be inferred by the additional

qualifying term. The term “situation” suggests a current event and the term

“threat” suggests a future event. For completeness, an example of an additional

qualifying term representing the past could be “incident”.

Another observation about

terms like…threat, situation and incident, is that they themselves can also be

considered a thing of interest. They are abstract things as opposed to real

things, but they can be a subject event of a message (i.e. a message that says

“we have a threat”). They can be “typed” (i.e. a threat of type “forest fire”),

and they do convey a sense that something is happening that is a deviation from

the normal state, so they can also be classified as events. NOTE: As a language

construct, the term “forest fire threat” is made up of the noun “threat” and a

noun adjunct “forest fire”. A noun adjunct is also a noun, but has been related

to adjunct status by its usage as a qualifier. A noun adjunct is not the

subject or object of a sentence.

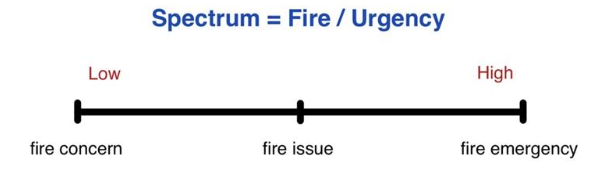

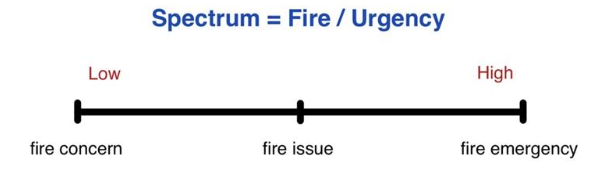

Alerts can be used to alert

audiences to events of interest that are minor, major, or anywhere in between.

If an additional qualifying term is used for an event term that infers an

urgency, such as “concern”, “problem”, “issue”, “warning”, “emergency”, etc…

there is an urgency based qualifying term present.

Another

observation about urgency based qualifying terms is that they themselves can

also be considered a thing of interest and can be typed. Just like past,

present and future qualifying terms, they are nouns and the same interpretation

applies.

Another

observation about urgency based qualifying terms is that they themselves can

also be considered a thing of interest and can be typed. Just like past,

present and future qualifying terms, they are nouns and the same interpretation

applies.

NOTE: the CAP-XML standard

already has an element that handles urgency. The <urgency> element is to

help consuming systems process the alert message when there is a need to

present the message differently based on the <urgency> setting. The

<urgency> value is meant for automated systems and is not initially meant

for the final audience. Any sense of urgency for the final audience should be

handled in the <headline> or <discussion> elements, but since the

<event> element is also meant for the final audience, many alerting

authorities have chosen to add urgency based qualifying terms there.

The intersection of spectrums

becomes important only when trying to compare terms from across spectrums. For

example, if one alert message uses an event term that includes a time

qualifying term at the narrow end of the broad to narrow spectrum, and another

alert message includes an urgency qualifying term at the broad end of the broad

to narrow spectrum, how difficult is it for automated systems to relate the two

terms when they should be related (i.e. an event term like “weather threat” as

compared to “hurricane emergency”).

Furthermore, there are cases

where individual event terms incorporate two spectrum terms (i.e. “fire threat

emergency”), or incorporate an abstract term on its own (i.e. “emergency”).

When this occurs, the terms used are very difficult to compare with other

terms. Again, OASIS has no jurisdiction over such alerting practices leaving that

up to the authorities themselves, but the varied practices do result in a wide

range of terms used making comparisons difficult.

Keeping all of the

discussions in mind, a sub-committee of the EMTC has attempted to compile a reference

list of subject event type terms that alerting authorities and originators can

use or reference in CAP alert messages. The concept of terms being part of a

spectra of terms was established as it factors into the ongoing task of

processing and managing new terms over time. Users of the list will not

necessarily have to be familiar with this spectrum concept, but it will help.

Contributors to the list however will have a better understanding of how their

submission is being treated if they understand the spectrum concept.

A spectrum, in the context

used here, where a grouping of terms is brought together under one defined

range, provides a means of comparing terms. With that, a number of spectrum

concepts arise and are introduced here and discussed below.

For every event term, there

are other related event terms that others may feel are better terms to use.

This is of course a matter of opinion but in a spectrum approach, the EMTC can

show a given term as relatable to other terms, even across the different

spectrums the term is a part of. If a reference term falls onto one or more

broad to narrow spectrums, all terms on those spectra are considered related

terms.

How narrow (or specific) do

event terms need to be? For example, a term for every intensity rating on the

Enhanced Fujita Scale (EF0 tornado to EF5 tornado), each based on the likely

damage expected with a tornado event, could arguably help consumers better

deliver alert messages to their audiences. If an <eventCode> existed for

each narrow term, the audience experience could be enhanced as the narrower

term increases the precision of the message.

In the example given, the

term is actually the code itself (i.e. “EF0”). However, for other scales, such

as a marine scale for wind speeds where a qualifying term is used (i.e. small

craft wind = 15-19 knots, strong wind = 20-33 knots, gales = 34-47 knots,

etc…), the discussion remains relevant.

In such cases however, it is

usually only smaller subset audiences that have a need for such specificity.

The EMTC purposely does not venture into the very narrow edge of the spectrum

feeling that the general public would be better served, as with the first

example, by the event term “tornado”, or in the second example, by the event term

“wind”. For those looking for more specificity of scale, the “Other Lists”

section below offers up a complimentary solution that CAP easily accommodates.

Preferred terms, within a

spectrum of terms, is a matter of opinion. The EMTC will not concern itself

with choosing a preferred term. Alerting authorities are free to choose their

preferred term when considering their audiences. The list however makes it

possible to compare the terms used with other terms preferred by other authorities.

Other language terms are

considered to be in the same spectrum. Spectrums are language independent. If a

term is used in one identified language, and it has an equivalent term in

another identified language, it is a related term. Filters by language can be

used to when working in one language (viewing the list), or when using the list

to translate from one language to another (processing CAP with the help of the

list).

CAP has the facility to house

term references from more than one list in any single CAP message. The

<eventCode> element is a multi-instanced element in CAP, specifically

defined to allow for codes from many different lists to be simultaneously

incorporated into a message. For that reason, the EMTC has decided not to

include terms and codes based on preferences or specificity of scale, leaving

that exercise up to sub-communities of users to define their own list.

Any such community is welcome

to define and publish additional event term codes. Those additional codes, if

necessary, can easily cover the narrow edge of the broad to narrow spectrum.

For an alert message that goes out to a multitude of consumers, serving both

specific and general audiences, an additional event code could convey the

preferred or specific details to subset

audiences and the EMTC code could convey general details to general audiences.

As mentioned in the outset,

the EMTC has developed a list of “event” terms for use in alert messaging

systems. There was no shortage of challenges with this initiative. Determining

how to build and structure the list first meant understanding the bulk of the

problems the list was intended to solve. Also, stewards of the list, as well as

users of the list, would each have their own objectives when working with the

list. Furthermore, how to apply and present the list afterwards to all users

was also difficult since many existing alerting practices are already underway

and had to be accommodated for in the methods chosen.

For users, the EMTC list was

developed to be open-ended. An open-ended approach is considered evergreen –

the resulting material retains its relevance by growing continuously to meet

the needs of a community. For the sub-committee, managing an open-ended

reference list, where new terms can be submitted over time, is possible, but

only when a solid process for upkeep is established. This is possible with the

concept of spectrums.

Secondly, strategies such as

a thesaurus approach emerge. With a thesaurus approach, each term is related to

other similar terms and by selecting one term, other similar or related terms

can be found using the various spectra the term can be found in. The thesaurus

then leads the user down a path where the user can choose for themselves the

best term as they deem appropriate for the situation. Through the spectrum

approach, the EMTC will be able to list related terms for any given reference

term when using a thesaurus.

For consumers of CAP, the <event> element is free form, and

consumer systems should already be accepting free form values for this element.

The terms in the EMTC list should not require any refactoring in those

consuming systems if those terms appear in CAP messages. This of course assumes

consumers use the <event> element for what it was intended – as a display

element only.

Secondly, for consumers that

want more – that want the ability to auto-process and compare event types

across systems and platforms – the EMTC is suggesting an alternative procedure

requiring the cooperation of CAP originators and consumers alike. The EMTC is

asking originators to populate one instance of the <eventCode> element

with a code value from the list – the value that most closely represents the

event type used by the alerting authority. For example, if the alerting

authority has an established event term that closely mirrors an EMTC term, the

following should be placed into any associated CAP message file.

<eventCode>

<valueName>OET:v1.0</valueName>”

<value>OET-537</value> --a coded value for the closest

EMTC event term

</eventCode>

If a term does not closely

resemble any EMTC term, then following is requested.

<eventCode>

<valueName>OET:v1.0</valueName>”

<value>OET-000</value> --a coded value for the EMTC

event term “other event”

</eventCode>

For alerting authorities, if one does not already have their own list, one may

freely use the terms from the EMTC list. If one already has their own event

terms list, the EMTC requests a mapping of those terms to equivalent terms in

the EMTC list by the CAP originator when generating an alert message (as

exampled above). The sub-committee will periodically expand the list and

release updated versions.

Secondly, the EMTC is also

asking authorities to submit terms for inclusion into the list. As mentioned,

the sub-committee will periodically expand the list but will only do so acting

as a custodian for the list rather than the subject matter experts for the

terms on the list. If there is a situation where the “other issue” coded value

is used in a CAP alert message, then the event type used in that message is a

candidate for inclusion on the EMTC list going forward.

The following is the general

procedure used when considering a new term for inclusion into the list.

-

An event term to

be supplied by an interested party

-

The event term to

be associated to one or more CAP categories by the interested party (to set the

broad edge of the spectra of interest)

-

An assessment of

whether it truly is an event term or not

-

A confirmation of

whether it truly fits the Spectrum or not

-

Once accepted the

term will be added to the list

o It will be roughly ordered within the

indicated broad to narrow spectra

o It will be assigned a new EMTC event

terms code if it has no sibling term

o It will be assigned an existing EMTC

event terms code if it has a sibling term

-

All other terms

in the associated spectra will be considered related terms

-

Suggestions for

other language terms will be accepted and added

o Equivalent other language terms will

be considered sibling terms

The sub-committee will only

review the terms as indicated above. For that, we need the help of the

submitting agency - either the alerting authority itself or an agency on behalf

of an alerting authority.

The list below demonstrates

what OASIS will accept…

1)

event terms that

convey a sense of time and space.

2)

event terms that

fall within a broad to narrow spectra of terms.

3)

multiple event

terms in different languages for a single event type.

4)

event terms that

are used to service multiple user communities, regardless of the number of

authorities it affects.

5)

event terms that

are regional event terms (i.e. “monsoon”).

6)

event terms that

are proxy terms (i.e. “AMBER Alert”), if the proxy term is well associated to

an event type.

7)

event terms that

are multi-word terms (i.e. “falling rock”) where the multi-words are needed to

convey the concept of an event.

8)

event terms

that collectively subsume a number of smaller events (i.e. “tropical storm”

which may subsume “wind”, “rain”, “high seas”, “flood”, etc…).

9)

event terms that

are secondary event terms when the secondary event is truly the subject event (e.g.,

“boil water advisory”, “evacuation order” or “AMBER alert”). The secondary

event is what the alerting authority is truly directing the attention of the

audience (for AMBER Alert, that secondary event is the search for the missing

child, as opposed to the original abduction event that triggered the AMBER

Alert).

10)

new mappings to

related terms (i.e., adding terms to other spectrums).

The list below is not a

complete list of ideas applicable to the process of not accepting event terms,

as new ideas may emerge, but the list does demonstrate what OASIS will not

accept…

1)

terms not

associated to an event (i.e., “terrorism).

The term

“terrorism” is not associated to an event, it is an ideology. It could however

be associated to an event with an additional qualifying term that convey a

sense of time and space, such as “active terrorism”. Regardless of whether

such terms are good terms to use or not, the additional word in the examples

creates the notion of possible event type. NOTE: “terrorist incident” is in the

event terms list as an event type, not the ideological concept. NOTE: This explanation

is not necessarily directly applicable in all languages however the intent

still applies.

2)

terms that are

actually alert terms (i.e. “thunderstorm warning”).

The term

“thunderstorm warning” is actually a secondary event term. It is a term that

refers to the act of issuing a warning, not the real or anticipated presence of

a thunderstorm event. Such secondary events are not what the CAP elements,

<severity>, <onset>, etc. were all created address. In this case,

the term “thunderstorm” will suffice. EXCEPTION: Some alert terms are actually

adopted as a way to describe secondary events where the secondary event is

truly the subject event (i.e. AMBER Alert). The term AMBER Alert was chosen to

represent the secondary event of a “coordinated child search”. The term AMBER

Alert was adopted to use the term alert to heighten the awareness of the

secondary event. Over time, it has become a well-known term associated to that

secondary event. It has effectively taken on a meaning of more than just what

the term on its own suggests and therefore is an acceptable event type term.

3)

terms that are

multi-word terms that use a subjective qualifier that only try to classify an

event by scale rather than distinguish the event from another event by its

nature (i.e., “gale force winds” and “hurricane force winds” are derived terms

based on a level marker). However, terms like “chemical fire” and “forest fire”

would each be accepted separately as the nature of the two events are quite

different. Therefore, the terms “gale force wind” and “hurricane force wind”

are considered too narrow for the OASIS event terms list, but the term “wind”

is acceptable. NOTE: Communities, such as marine based communities, are welcome

to establish a set of terms and codes for scale based terms with the

recommendation that the terms be mapped to the closest OASIS term (and

associated event code), and include a reference to the OASIS event code in one

instance of the multi-instanced CAP <eventCode> element.

4)

terms that are

multi-word terms where the subjective qualifier is scale based but not

necessarily tied to a known level marker from the perspective of the intended

audience. For example, “severe thunderstorm”, which has an implied level marker

based on the word “severe” but by its use only implies an event more hazardous

than normal”. Therefore, the term “severe thunderstorm” is considered too

narrow for the OASIS event terms list, but the term “thunderstorm” is

acceptable. NOTE: Communities, such as meteorological based communities, are

welcome to establish a set of terms and codes for scale based terms with the

recommendation that the terms be mapped to the closest OASIS term (and

associated event code), and include a reference to the OASIS event code in one

instance of the multi-instanced CAP <eventCode> element.

5)

accept proxy

terms that are otherwise not event terms (i.e., “Red”).

Red is not an

event on its own, it is a quality. “Red” may be used by the authority in the

<headline>, <description>, <parameter> or other elements as

an alerting authority based preferred term but as an event these terms do not

convey the idea of an event. Multi-word terms that try to make an event out of

a proxy event (i.e., “red event”) are also not accepted. Turning the proxy

event into an event in this manner provides no context to the term event.

The following individuals have participated in the creation

of this specification and are gratefully acknowledged:

Participants:

Alagna, Michael IJIS

Institute

Beavin, Mr. William The

Boeing Company

Bredenberg, Mr. Patrick Oracle

Bui, Dr. Thomas The

Boeing Company

Calabrese, Stefano Presidenza

del Consiglio dei Ministri - Dipartimento della Protezione Civile

Casanave, Cory Object

Management Group

Chiesa, Mr. Chris Pacific

Disaster Center

Chown, Bill Siemens

AG

Clark, James Bryce OASIS

Considine, Toby University

of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Cox, William Individual

Denning, Paul Mitre

Corporation

Devanesan, Ms. Ruha Google

Inc.

Dominguez, Mr. Alain Ministere

de L'Interieur-France

Embley, Mr. Paul National

Center for State Courts

Ensign, Mr. Chet OASIS

Ferguson, James Kaiser

Permanente

Ferrentino, Thomas Individual

Gerber, Mike NOAA/NWS

Gustafson, Mr. Robert Mitre

Corporation

Hakusa, Mr. Steve Google

Inc.

Hardy, Dr. Andrea NOAA/NWS

Kenyon, Alfred DHS

Office of Cybersecurity and Communications (CS&C)

Laughren, Ms. Emily Mitre

Corporation

Leinenweber, Lewis Open

Geospatial Consortium, Inc. (OGC)

Lucero, Mr. Mark DHS

Office of Cybersecurity and Communications (CS&C)

McKeeman, Mr. Neil University

of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Merkle, Mr. Thomas DHS

Office of Cybersecurity and Communications (CS&C)

Myhre, Mr. Joel Pacific

Disaster Center

Paulsen, Norm Environment

Canada

Percivall, Mr. George Open

Geospatial Consortium, Inc. (OGC)

Riga, Mr. Thomas Google

Inc.

Rosini, Mr. Umberto Presidenza

del Consiglio dei Ministri - Dipartimento della Protezione Civile

Roy, Donna DHS

Office of Cybersecurity and Communications (CS&C)

Schaffhauser, Andreas EUMETNET

Schur, Mrs. Dee OASIS

Streetman, Mr. Steve DHS

Office of Cybersecurity and Communications (CS&C)

Waters, Jeff US

Department of Defense (DoD)

Webber, Mr. David Huawei

Technologies Co., Ltd.

Westfall, Jacob Individual

White, Mr. Herbert NOAA/NWS

Wilkins, Mr. Brian Mitre

Corporation

Brooks, Rex Individual

Ham, Mr. Gary Individual

Jones, Mrs. Elysa Individual

Paulsen, Norm EnvironmentCanada

Robertson, Dr. Scott Kaiser

Permanente

Weber, Ms. Sabrina IEM

The OASIS event

code value is for use in the cap.alertInfo.eventCode.value element

Note: “OET”

represents “OASIS Event Term”

The version of

the OASIS Event Terms list that the OASIS event code is taken from is indicated

in the cap.alertInfo.eventCode.valueName element.

Note: It is of

the form "OET:m.n", where "m.n" is the

major.minor version of this document.

The OASIS event

term is for use in the cap.alertInfo.event element

Note: The OASIS

Event Term is supporting material for comparison purposes and for systems that

have no Event term list.

The

"Grouping" column is used to indicate other CAP Event terms which are

related.

Note:

Most often, the grouping term is a broad grouping term on the broad to narrow

spectrum, where the term on the row is a more specific term on the same

spectrum. The Grouping term can lead to other related terms if the given Event

term "doesn't quite fit" the situation.

The CAP

Category Code(s) value is for use in the cap.alertInfo.category element

Note: The

"CAP Category Code(s)" column, lists the known CAP Categories the

OASIS Event term is associated, and OASIS recommends all values listed should

be included in the multi-instanced cap.alertInfo.category element in a CAP

message.

|

OASIS Event Code

|

OASIS CAP Event Term

|

Grouping

|

CAP Category Code(s)

|

|

OET-000

|

other

event

|

other

|

Other

|

|

OET-001

|

active

shooter situation

|

criminal

activity

|

Safety;

Security

|

|

OET-002

|

administrative

activity

|

testing

& system activity

|

Other

|

|

OET-003

|

air hazard

|

aviation

hazard

|

Meteorological;

Transport

|

|

OET-004

|

air

quality

|

health

hazard

|

Environmental;

Health

|

|

OET-005

|

air search

|

safety hazard

|

Meteorological

|

|

OET-006

|

air

stagnation

|

air

hazard

|

Meteorological

|

|

OET-007

|

aircraft

crash

|

aviation

hazard

|

Transport

|

|

OET-008

|

aircraft

incident

|

aviation

hazard

|

Transport

|

|

OET-009

|

airport

closure

|

aviation

hazard

|

Transport

|

|

OET-010

|

airspace

closure

|

aviation

hazard

|

Transport

|

|

OET-011

|

airspace

restriction

|

aviation

hazard

|

Transport

|

|

OET-012

|

ambulance

|

health

issue

|

Health

|

|

OET-013

|

animal

disease

|

health issue

|

Health

|

|

OET-014

|

animal

feed

|

health

issue

|

Health

|

|

OET-015

|

animal health

|

health issue

|

Health

|

|

OET-016

|

arctic

outflow

|

temperature

hazard

|

Meteorological

|

|

OET-017

|

ashfall

|

air hazard;

marine; aviation

|

Geological;

Health; Meteorological; Safety; Transport

|

|

OET-018

|

avalanche

|

|

Geological

|

|

OET-019

|

aviation

hazard

|

aviation

hazard

|

Transport

|

|

OET-020

|

aviation

security

|

aviation

hazard

|

Transport;

Security

|

|

OET-021

|

beach hazard

|

marine

|

Safety

|

|

OET-022

|

biological

|

biological

hazard

|

CBRNE

|

|

OET-023

|

blizzard

|

winter

weather

|

Meteorological

|

|

OET-024

|

blood

supply

|

health

issue

|

Health

|

|

OET-025

|

blowing dust

|

air hazard

|

Meteorological

|

|

OET-026

|

blowing

snow

|

winter

weather

|

Meteorological

|

|

OET-027

|

blue-green

algae

|

water hazard

|

Environmental

|

|

OET-028

|

bomb

threat

|

criminal

activity

|

CBRNE

|

|

OET-029

|

bridge

closure

|

road hazard

|

Transport

|

|

OET-030

|

bridge

collapse

|

road

hazard

|

Transport

|

|

OET-031

|

building

collapse

|

infrastructure

issue

|

Infrastructure

|

|

OET-032

|

building

structure hazard

|

earthquake

|

Geological

|

|

OET-033

|

bush fire

|

fire

|

Fire

|

|

OET-034

|

cable

service issue

|

utility

issue

|

Infrastructure

|

|

OET-035

|

canal

|

utility issue

|

Infrastructure

|

|

OET-036

|

chemical

fire

|

fire

|

CBRNE;

Fire

|

|

OET-037

|

chemical

hazard

|

|

CBRNE

|

|

OET-038

|

child

abduction

|

criminal

activity

|

Safety;

Security

|

|

OET-039

|

civil

|

civil issue

|

Security

|

|

OET-040

|

civil

protest

|

civil

issue

|

Safety

|

|

OET-041

|

coal gas

|

utility issue

|

Infrastructure

|

|

OET-042

|

coastal

flood

|

flood

|

Meteorological

|

|

OET-043

|

cold

|

temperature

hazard

|

Meteorological

|

|

OET-044

|

cold

weather

|

winter

weather

|

Meteorological

|

|

OET-045

|

communications

service disruption

|

utility issue

|

Infrastructure

|

|

OET-046

|

contagious

disease

|

health

hazard

|

Health

|

|

OET-047

|

contaminated

water

|

health hazard

|

Health

|

|

OET-048

|

contamination

|

|

CBRNE;

Health

|

|

OET-049

|

criminal

activity

|

criminal

activity

|

Safety

|

|

OET-050

|

cybercrime

threat

|

criminal

activity

|

Safety;

Security

|

|

OET-051

|

cyclone

|

tropical

storm

|

Meteorological

|

|

OET-052

|

dam

break

|

flood

|

Geological;

Meteorological

|

|

OET-053

|

dam issue

|

infrastructure

issue

|

Infrastructure

|

|

OET-054

|

dangerous

animal

|

civil

issue

|

Safety

|

|

OET-055

|

dangerous

person threat

|

criminal

activity

|

Safety

|

|

OET-056

|

debris

flow

|

geophysical

|

Geological

|

|

OET-057

|

demonstration

|

testing &

system activity

|

Other

|

|

OET-058

|

dense

fog

|

air

hazard

|

Meteorological

|

|

OET-059

|

dense smoke

|

air hazard

|

Meteorological

|

|

OET-060

|

diesel

fuel issue

|

utility

issue

|

Infrastructure

|

|

OET-061

|

disease

|

health issue

|

Health

|

|

OET-062

|

disease

outbreak

|

health

issue

|

Health

|

|

OET-063

|

drought

|

weather

|

Meteorological

|

|

OET-064

|

drug

safety

|

public

health

|

Health

|

|

OET-065

|

drug supply

|

public health

|

Health

|

|

OET-066

|

dust

storm

|

air

hazard

|

Meteorological

|

|

OET-067

|

dyke break

|

flood

|

Meteorological

|

|

OET-068

|

earthquake

|

earthquake

|

Geological

|

|

OET-069

|

electronic

infrastructure

|

infrastructure

issue

|

Infrastructure

|

|

OET-070

|

emergency

responder incident

|

criminal

activity

|

Safety

|

|

OET-071

|

emergency

responder threat

|

criminal activity

|

Safety

|

|

OET-072

|

emergency

support facilities incident

|

infrastructure

issue

|

Infrastructure

|

|

OET-073

|

emergency

support services incident

|

infrastructure

issue

|

Infrastructure

|

|

OET-074

|

emergency

telephone outage

|

infrastructure

issue

|

Infrastructure

|

|

OET-075

|

environmental

issue

|

environment

|

Environmental

|

|

OET-076

|

explosion

threat

|

civil

issue

|

CBRNE

|

|

OET-077

|

falling

object

|

safety hazard

|

Safety

|

|

OET-078

|

fire

|

fire

|

Fire

|

|

OET-079

|

flash flood

|

flood

|

Meteorological

|

|

OET-080

|

flash

freeze

|

winter

weather

|

Meteorological

|

|

OET-081

|

flood

|

flood

|

Meteorological

|

|

OET-082

|

fog

|

air

hazard; winter weather

|

Meteorological

|

|

OET-083

|

food

contamination

|

biological

hazard

|

Health

|

|

OET-084

|

food

safety

|

public

health

|

Health

|

|

OET-085

|

food supply

|

public health

|

Health

|

|

OET-086

|

forest

fire

|

fire

|

Fire

|

|

OET-087

|

freeze

|

winter

weather

|

Meteorological

|

|

OET-088

|

freezing

drizzle

|

winter

weather

|

Meteorological

|

|

OET-089

|

freezing rain

|

winter

weather

|

Meteorological

|

|

OET-090

|

freezing

spray

|

winter

weather; marine

|

Meteorological

|

|

OET-091

|

frost

|

winter

weather

|

Meteorological

|

|

OET-092

|

fuel

issue

|

utility

issue

|

Infrastructure

|

|

OET-093

|

geophysical

issue

|

geological

|

Geological

|

|

OET-094

|

grass

fire

|

fire

|

Fire

|

|

OET-095

|

hail

|

severe

weather

|

Meteorological

|

|

OET-096

|

hazardous

seas

|

marine

|

Transport

|

|

OET-097

|

health issue

|

health issue

|

Health

|

|

OET-098

|

heat

|

temperature

hazard

|

Meteorological

|

|

OET-099

|

heating oil

issue

|

utility issue

|

Infrastructure

|

|

OET-100

|

high

seas

|

marine

|

Meteorological

|

|

OET-101

|

high surf

|

marine

|

Meteorological

|

|

OET-102

|

high

tide

|

marine

|

Transport

|

|

OET-103

|

high water

|

utility

issue; marine

|

Infrastructure;

Transport

|

|

OET-104

|

home

crime

|

criminal

activity

|

Safety

|

|

OET-105

|

humidity

issue

|

temperature

hazard

|

Meteorological

|

|

OET-106

|

hurricane

|

tropical

storm; tropical cyclone

|

Meteorological

|

|

OET-107

|

ice

|

winter

weather

|

Meteorological

|

|

OET-108

|

ice

pressure issue

|

ice

issue

|

Meteorological

|

|

OET-109

|

ice storm

|

winter

weather

|

Meteorological

|

|

OET-110

|

iceberg

|

ice

issue

|

Meteorological

|

|

OET-111

|

industrial

crime

|

criminal

activity

|

Safety

|

|

OET-112

|

industrial

facility

|

safety

hazard

|

Safety

|

|

OET-113

|

industrial

fire

|

fire

|

Fire

|

|

OET-114

|

infrastructure

|

infrastructure

|

Infrastructure

|

|

OET-115

|

internet

service

|

utility issue

|

Infrastructure

|

|

OET-116

|

lake

effect snow

|

winter

weather

|

Meteorological

|

|

OET-117

|

lake wind

|

air hazard

|

Meteorological

|

|

OET-118

|

landline

service

|

utility

issue

|

Infrastructure

|

|

OET-119

|

landslide

|

geophysical

|

Geological

|

|

OET-120

|

law

enforcement

|

civil

issue

|

Security

|

|

OET-121

|

levee break

|

flood

|

Meteorological

|

|

OET-122

|

lightning

|

thunderstorm;

severe weather

|

Meteorological

|

|

OET-123

|

limited

visibility

|

air hazard

|

Transport

|

|

OET-124

|

low

tide

|

marine

|

Transport

|

|

OET-125

|

low water

|

utility

issue; marine

|

Infrastructure;

Transport

|

|

OET-126

|

low

water pressure

|

utility

issue

|

Infrastructure

|

|

OET-127

|

meteoroid

|

space

|

Transport

|

|

OET-128

|

meteorological

issue

|

meteorological

|

Meteorological

|

|

OET-129

|

missile

threat

|

national

hazard

|

CBRNE

|

|

OET-130

|

missing

person(s)

|

safety

hazard

|

Safety

|

|

OET-131

|

mobile communication

|

utility issue

|

Infrastructure

|

|

OET-132

|

monsoon

|

weather

|

Meteorological

|

|

OET-133

|

mudslide

|

geophysical

|

Geological

|

|

OET-134

|

natural

gas

|

utility

issue

|

Infrastructure

|

|

OET-135

|

network

message notification

|

testing &

system activity

|

Other

|

|

OET-136

|

nuclear

power plant

|

infrastructure

issue

|

Infrastructure;

CBRNE

|

|

OET-137

|

oil leak

|

beach hazard,

environmental

|

Environmental

|

|

OET-138

|

oil

spill

|

beach

hazard, environmental

|

Environmental

|

|

OET-139

|

over water

search

|

search

|

Rescue

|

|

OET-140

|

overland

flood

|

flood

|

Meteorological

|

|

OET-141

|

overland

search

|

search

|

Rescue

|

|

OET-142

|

pipeline

rupture

|

utility

issue

|

Infrastructure

|

|

OET-143

|

plant health

issue

|

health issue

|

Health

|

|

OET-144

|

potable

water

|

utility

issue; water hazard

|

Infrastructure

|

|

OET-145

|

power outage

|

infrastructure

issue

|

Infrastructure

|

|

OET-146

|

power

utility

|

utility

issue

|

Infrastructure

|

|

OET-147

|

practice

|

testing &

system activity

|

Other

|

|

OET-148

|

product

safety

|

safety

hazard

|

Safety

|

|

OET-149

|

public

facility

|

infrastructure

issue

|

Infrastructure

|

|

OET-150

|

public

health

|

health

issue

|

Health

|

|

OET-151

|

public

service issue

|

infrastructure

issue

|

Infrastructure

|

|

OET-152

|

public

transit issue

|

infrastructure

issue

|

Transport

|

|

OET-153

|

pyroclastic

flow

|

volcano

hazard

|

Geological

|

|

OET-154

|

radiation

|

radiological

hazard

|

CBRNE

|

|

OET-155

|

radio

transmitter

|

safety hazard

|

Infrastructure

|

|

OET-156

|

radioactive

material release

|

radiological

hazard

|

CBRNE

|

|

OET-157

|

radiological

fire

|

fire

|

CBRNE; Fire

|

|

OET-158

|

railway

issue

|

infrastructure

issue

|

Transport

|

|

OET-159

|

rain

|

weather

|

Meteorological

|

|

OET-160

|

rapid

ice closing of water passage

|

ice

issue

|

Transport

|

|

OET-161

|

red tide

|

health issue;

marine issue

|

Health

|

|

OET-162

|

rescue

|

rescue

|

Rescue

|

|

OET-163

|

retail crime issue

|

criminal

activity

|

Safety

|

|

OET-164

|

rip

current issue

|

beach

hazard

|

Safety

|

|

OET-165

|

road closure

|

road hazard

|

Transport

|

|

OET-166

|

road

issue

|

road

hazard

|

Transport

|

|

OET-167

|

road vehicle

accident

|

road hazard

|

Transport

|

|

OET-168

|

rogue

waves

|

marine

|

Geological

|

|

OET-169

|

safety

|

safety hazard

|

Safety

|

|

OET-170

|

sandstorm

|

air

hazard; weather

|

Meteorological

|

|

OET-171

|

satellite

debris

|

space

|

Other

|

|

OET-172

|

satellite

service

|

utility

issue

|

Infrastructure

|

|

OET-173

|

school bus

issue

|

infrastructure

issue

|

Transport

|

|

OET-174

|

school

closing

|

infrastructure

issue

|

Infrastructure

|

|

OET-175

|

school

lockdown

|

infrastructure

issue

|

Infrastructure

|

|

OET-176

|

search

event

|

search

|

Rescue

|

|

OET-177

|

security

|

security

|

Security

|

|

OET-178

|

sewer

|

utility

issue

|

Infrastructure

|

|

OET-179

|

shoreline

threat

|

beach hazard

|

Safety

|

|

OET-180

|

sinkhole

|

safety

hazard

|

Safety

|

|

OET-181

|

sleet

|

winter

weather

|

Meteorological

|

|

OET-182

|

snow

|

winter

weather

|

Meteorological

|

|

OET-183

|

snowstorm

|

weather

|

Meteorological

|

|

OET-184

|

space

debris

|

space

|

Other

|

|

OET-185

|

space weather

|

space

|

Other

|

|

OET-186

|

squall

|

weather;

marine

|

Meteorological

|

|

OET-187

|

storm

|

weather;

marine

|

Meteorological

|

|

OET-188

|

storm

drain

|

utility

issue

|

Infrastructure

|

|

OET-189

|

storm surge

|

weather;

flood

|

Meteorological

|

|

OET-190

|

structure

fire

|

fire

|

Fire

|

|

OET-191

|

swells

|

marine

|

Safety;

Transport

|

|

OET-192

|

telephone

|

utility

issue

|

Infrastructure

|

|

OET-193

|

terrorist

incident

|

criminal

activity

|

Safety

|

|

OET-194

|

thunderstorm

|

weather

|

Meteorological

|

|

OET-195

|

tornadic

waterspout

|

severe

weather

|

Meteorological

|

|

OET-196

|

tornado

|

severe

weather; tornado

|

Meteorological

|

|

OET-197

|

toxic plume

|

contamination

hazard

|

CBRNE

|

|

OET-198

|

toxic

spill

|

contamination

hazard

|

CBRNE

|

|

OET-199

|

traffic

|

road hazard

|

Transport

|

|

OET-200

|

transportation

|

transport

|

Transport

|

|

OET-201

|

tropical

depression

|

tropical

storm; tropical cyclone

|

Meteorological

|

|

OET-202

|

tropical

storm

|

weather;

tropical cyclone

|

Meteorological

|

|

OET-203

|

tsunami

|

marine

|

Geological

|

|

OET-204

|

typhoon

|

tropical

cyclone

|

Meteorological

|

|

OET-205

|

ultraviolet

|

safety

|

Safety

|

|

OET-206

|

utility

|

utility

issue

|

Infrastructure

|

|

OET-207

|