The

Emergency Management Technical Committee (EMTC) of OASIS Open,

has developed this OASIS Open Event Terms List - User’s Guide

to support the objective of interoperability in the business-of-alerting.

Interoperability is the term given to systems working together for a common

cause, and this guide addresses an important aspect of that cause – the handling

of information associated with an event deemed worthy of being

alerted for. Event information is a key piece of the overall information in the

situation.

This

User’s Guide discusses the concept of an event across the alerting process –

throughout the originating phase to the consuming phase.

The aim is to help originating agents provide standardized (and interoperable)

alert-worthy event information in alert messages for consuming agents

in the process .

This guide has been constructed to address both the observation and analysis of

an event, and the larger alerting situation the event creates for

an alerting audience.

Interoperability

is a primary objective of the EMTC and many of the Common Alerting

Protocol (CAP) based alerting systems that operate world-wide. Many of

these systems are digitally connected – originating and/or consuming CAP-based messages

on a routine basis. CAP messages are XML-based document files

where interoperability is a key objective in its design. CAP is a means for alerting

practitioners (a term used to combine originators and consumers

into one reference), to exchange alerting information in a standardized way.

In

this guide, the premise is that an event is identified and an alerting process

is set to begin. Once the event’s significance is confirmed, it is designated as

an event-of-interest, and the analysis broadens to encompass the

entire alerting situation (inclusive of the event and the alerting process).

Addressing the situation, from the event inception to the audience notification,

is what OASIS Open considers to be an alerting service. The OASIS Open

Event Terms List - User’s Guide makes frequent reference to CAP in discussing

this service .

Prior

to this User’s Guide, OASIS Open had already published version 1.0 of an

OASIS Open Event Terms List resource. The resource was a

work product published for the purposes of promoting interoperability between

alerting practitioners. Subsequent to publishing, many practitioners requested

guidance on how the content of the list is best integrated within CAP. With OASIS

Open Event Terms List - User’s Guide v1.0, and with a backwards

compatible OASIS Open Event Terms List - Lookup Table v2.0, practitioners

now have guidance on how to incorporate the OASIS Open managed list of

universal event terms and codes into their service.

The

OASIS Open Event Terms List - User’s Guide is less for the casual

reader, and more for the expert practitioner (e.g. service architect,

system designer, processing agent, etc.). The aim is to help practitioners build

and operate a better system - one that connects seamlessly (i.e.

is interoperable) with agencies and audiences

on a business/client level, and with originating and consuming

agents on a technical/functional level.

The

CAP standard is a proven data standard for obtaining this goal.

It is a standard for conveying all-event, all-alert

information in an end-to-end alerting system devoted to the alerting objective.

The CAP standard allows for a “many-originator” to “many-consumer”

transfer of information on the technical and functional level, including

the use of customized alerting information (if needed), in any originator/consumer

relationship.

The

focus of this User’s Guide - the alert-worthy event

and its larger alerting situation

- is just one key component of alerting information to be conveyed to consuming

agents and audiences. To that end, the User’s Guide discusses how

to organize, structure, format, and subsequently originate and consume, the

following event-based information within a CAP alert message:

a)

the nature

of an event;

b)

the impacts

of an event;

c)

the location

and timing of an event;

d)

the event

and its relationship to any associated secondary events; and

e)

the calls-to-action

the event may warrant.

The

guide also discusses the tasks of the various processing agents involved in the

alerting service. This includes:

a)

the business

front-line alert originators (observers, analysts, social scientists);

b)

the

technical and functional back-line CAP originators (builders, publishers, data

operators);

c)

the technical

and functional back-line CAP consumers (aggregators, re-distributers,

presenters).

It

is the back-line consuming agents that are employed to service the target

alerting audience. It is the front-line originating agents that start the

process.

This

User’s Guide is also part of a series of event-focussed alerting resources

prepared by the OASIS Open EMTC to cover the full spectrum of

event-based information in a business-of-alerting.

The

OASIS Open Event Terms List (ETL) is a collection of 4 resources.

-

Event

Terms List - Lookup Table

-

Event

Terms List - User’s Guide

-

Event

Terms List - Concept Guide

-

Event

Terms List - Spectrum Analysis

The

OASIS Open Event Terms List - User’s Guide, as part of this collection,

will make reference to the other resources as needed. For more on a compiled

list of OASIS Open event terms and codes, see the OASIS Open Event

Terms List – Lookup Table. For more on understanding the basic

characteristics of an event, including ways to classify the nature, impacts,

location, timing, and behaviors of an event, see the OASIS Open Event

Terms List – Event Concepts. And finally, for more on understanding the

naming of events, and social science that accompanies those naming decisions,

see the OASIS Open Event Terms List – Spectrum Analysis.

The

OASIS Open Event Terms List - User’s Guide resource

was compiled to provide guidance for originating agencies and

their agents on how to select the best terms and codes from the OASIS

Open Event Terms List - Lookup Table, and how consuming

agencies and their agents can subsequently process the chosen terms

and codes. If alerting practitioners (originators and consumers)

are only looking to obtain a basic level of functionality with this material (i.e.

its standardized use and its basic benefit of interoperability), the

subsections marked as “Basic” in section 4 will suffice. With the

guidance of this User’s Guide, the OASIS Open EMTC is asking all CAP practitioners

to minimally incorporate the “Basic” function of the OASIS Open Event

Terms List into their business-of-alerting service to further the

objective of interoperability.

However,

if the practitioner is looking to take full advantage of the OASIS Open

Event Terms List, and gain a deeper understanding of events and the alerting

situation in the process, the subsections marked “More advanced” and “Fully

advanced” in section 4 are recommended. The advanced material presented

makes it possible to handle any conceivable type of event that may be considered

an event-of-interest worth alerting for.

This

Users’ Guide breaks down the process of creating a subject event –

the topic of discussion in an alert message. It does this by utilizing a series

of event-based sub-processes appropriate for various entities involved in the

exercise. It begins with an observing sub-process, followed by an analyzing

sub-process, leading to a CAP originating process, and ending with a CAP

consuming process .

An

OASIS Open Alerting Practices and Strategies - Glossary

(forthcoming) is a resource being assembled to house terms from across the many

OASIS Open alerting based resources. Terms that are both bold and underlined,

in this and other resources, are terms that can be found in the glossary. The

first time a term is used in a section of a resource, that is also found in the

glossary, it will be bolded and underlined to let the reader know there is a

provided definition in the glossary. Being familiar with the defined terms will

help with using this guide and will make navigating the resource quicker and

easier.

This

guide is also intended to help alerting agencies build a better system.

Most existing alerting system documentation, whether that documentation

is based on business analysis, business requirements,

system specifications, service, or training;

have been observed to use a mixture of terms from different views into the

process. Mixing views can lead to confusion for agents building,

operating, and promoting alerting systems. This guide does not go into actual

system design, but learning the language of the various processes used here

will help avoid some of the problems system builders often encounter .

This presentation of the OASIS Open

Event Terms List – User’s Guide is a Public Review presentation.

In this particular presentation all feedback will be collected and reviewed.

Suggestions, comments, and questions can be on any content, including the terms

and codes found in the OASIS Open Event Terms List – Lookup Table.

Each feedback item may be used to adjust the final release copies of the OASIS

Open Event Terms List family of resources (as applicable).

OASIS Open

plans to publish a set of resources in roughly the

following order as a best effort exercise (with no set timeline due to the

inability to predict the availability of volunteer resources):

1)

OASIS Open Event Terms List –

Lookup Table v2.0

2)

OASIS Open Event Terms List –

User’s Guide v1.0

3)

OASIS Open Alerting Practices and

Strategies – Glossary v1.0 (forthcoming)

4)

OASIS Open Event Terms List – Concept

Guide v1.0 (forthcoming)

5)

OASIS Open Event Terms List –

Spectrum Analysis v2.0 (forthcoming)

6)

OASIS Open Event Terms List –

Lookup Table v2.1 (planned)

7)

OASIS Open Alerting Practices and

Strategies – Glossary v1.1 (planned)

8)

OASIS Open Event Terms List –

User’s Guide v2.0 (planned)

9)

OASIS Open Event Terms List – Concept

Guide v2.0 (planned)

At the end of this publish cycle all resources,

in the family of OASIS Open Event Terms List

resources, will be at v2.0, with the Lookup Table having advanced to

v2.1 or greater. All version 2.X resources will be jointly compatible as a

package, all anchored to version 2.0.

The

following is a suggested list of tasks as recommended by the OASIS Open EMTC

when conducting an event-based alerting process. Each ordered

task aligns with the objectives and processes discussed in this User’s Guide

and with the material covered in the OASIS Open Event Terms List

family of resources. Many of the descriptive terms used in this list are

discussed in detail in the OASIS Open Event Terms List – Concept Guide.

Originating agents:

a)

Observe

and

identify an event situation (single or complex );

b)

Analyse

the events

in the situation and devise and form the events-of-interest (an event-of-interest

could cover the entirety of the event situation, or any subset part of the

situation, with each dependent upon the nature of it’s conditions

and impacts);

c)

Devise and form the alert-worthy

events for the target client (an alert-worthy event could also cover the

entirety of the situation, or any subset part of the situation, with each

dependent upon the nature of it’s conditions, impacts,

location and timing);

d)

Associate

the alert-worthy

events with other associated secondary events-of-interest to devise and form a subject

event for the alerting process (there is wide leeway to what

constitutes a subject-event). Subject events may be composed of a single event,

a complex event, or an even larger complex event once all the secondary events

are taken into consideration);

e)

Assemble

the

larger alerting-situation information (this includes information on the

subject-event; any and all supporting information; and any lead time,

intersection time, and follow time information the target audience needs for

coping with the subject event). This also includes using terms and codes as

given in the OASIS Open Event Terms List;

f)

Originate an alert (the

process of publishing one or more alert messages, ideally in CAP form, to

address the larger alerting situation).

Consuming agents:

a)

Initiate or confirm a connection

(for consuming CAP messages);

b)

Consume messages for processing;

c)

Interrogate each alert message and

subject event (for filtering, routing and presenting purposes);

d)

Establish, and if necessary

maintain, an alert notification signal for either:

a.

the

next agent along the path of distribution, or

b.

the last-mile

target audience at the end of the path of distribution.

In

this User’s Guide, a variety of larger alerting situations are

exampled. The

terms used in the examples are associated to one or more of the event-based processes

as discussed in the OASIS Open Event Terms List – Concept Guide. With the Concept

Guide and this User’s Guide, there are four main processes

(sub-processes to the overall process), that attributed to the four main identifiable

parties involved in the alerting process.

1)

“Observing”

process: a process that pertains to agencies and agents responsible for observing

and identifying events.

2)

“Analyzing”

process:

a process that pertains to agencies and agents responsible for analysing events,

events-of-interest, alert-worthy events, and subject

events, all for the purpose of potentially alerting for them .

3)

“CAP

Originating” process: a process that pertains to agents responsible for originating

a CAP-based alert message.

4)

“CAP

Consuming” process: a process that pertains to agents and audiences found at

the end of the path-of-distribution of a CAP-based alert message.

In

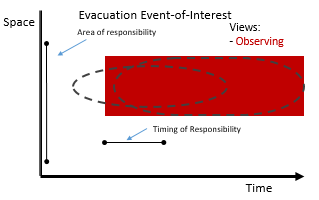

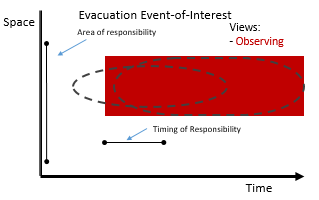

the “Observing” process, the objective is to identify any events, and

any secondary related events, as potential events-of-interest, specifically

for the purposes of advancing the alerting process. Events-of-interest can be

singular events (one identifiable event) or complex events (two or more

identifiable events that together as a group are considered one larger event).

They are identified by their nature (i.e. by their observed condition

and impact) .

In

the “Analyzing” process, the objective is to reconcile the details of

the events-of-interest from the perspective of impacted parties. The process

takes the event situation and establishes a communication framework for

the forthcoming alerting situation (i.e. the agency/audience interaction

and all which that encompasses). It is here where alert-worthy events,

the subject event, and any noteworthy secondary events, are

clarified. It also where new events, such as solicited action events the

alerting agency is asking of impacted parties (i.e. any actions to take during

the lead time (ahead of the event), the intersection time (during the event) and

the follow time (after the event) all due to instance and occasion of the

subject event).

In

the CAP Originating process, the objective is to clarify the pieces of

information that support originators building a proper alert message using the

CAP standard. Elements of information in the CAP model are designed to make the

exchange of information meaningful to all parties. The aim of CAP originating

parties is to create a set of standardized elements of technical and functional

alerting information for agents of their consuming client’s needs.

One

objective of the User’s Guide is to make the originating process easier

while simultaneously meeting the needs of all the various consuming parties. The

OASIS Open EMTC perspective for CAP originators is to not necessarily have

them create separately structured CAP product for each and every CAP consuming

party, but to have one CAP message that can service them all . The CAP

standard is designed to make this possible .

In

the CAP Consuming process, the objective is to clarify the pieces of

information that support consumers processing a proper alert message based on

the CAP standard. Elements of information in the CAP model are designed to make

the exchange of information meaningful to all parties with the aim of having consuming

parties able to properly use the elements for their needs.

One

objective the User’s Guide is to make the consuming process

easier while simultaneously allowing originating parties the ability to service

all their consuming partners simultaneously with the same set of CAP alert

messages. The OASIS Open EMTC perspective for CAP consumers is to not

have them make improper assumptions on the information received, nor have to

create additional information to make their service successful. The CAP

standard was designed to make this possible .

This section

outlines the foundational alerting workflow that underpins the four business-of-alerting

processes defined in the OASIS Open Event Terms List family of resources.

It reinforces terminology introduced in the Concept Guide and

introduces additional terms as required.

Following the

process discussion, a representative event situation is presented. This

scenario serves as a baseline case for establishing a set of baseline steps

that can be adapted to a variety of real-world situations. These steps form the

backbone of consistent alerting practices across event types.

The Example

Situations section of this guide builds upon this baseline by exploring

case-specific variations. While these examples retain the core principles

outlined here, they also highlight distinctive circumstances and considerations

unique to each scenario. The primary focus remains on the concept of "event,"

while other components of the alerting process (alerting signals, layers,

profiles, over-alerting, etc…), are covered in separate documents within the OASIS

Open set of resources

.

The

process accommodates both single-event and complex-event

scenarios. Complex-events often involve multiple events as observed and are

explored in depth in this guide. Single-events are treated as subsets of

complex-events and serve as entry points for new users. Learning to manage

single-event scenarios is encouraged before tackling complex-event cases .

The baseline case

presented here involves a complex-event that associates several individual

single-events into one event situation. It is analyzed through three

lenses:

·

Simple

alerting situation (picking one event at exclusion of the others)

·

Advanced

alerting situation (picking two events that can easily be aggregated into one

larger event)

·

Fully

advanced alerting situation (picking four events that are all associated with

each as suggested by business policy and the example event situation as given).

Each perspective

demonstrates how the Common Alerting Protocol (CAP) standard's features can be

leveraged effectively

.

This

guide presents a comprehensive, end-to-end sequence for alerting, beginning with

the observation of an event (real or imagined ), and concluding with an

alert notification of a subject event to the alerting agency’s target

audience. While the steps are described broadly, some components of the

baseline process may be unfamiliar to certain agencies.

This example

baseline case serves as the universal reference model for all subsequent

examples provided in the Example Situations section. Unless

explicitly stated, the principles outlined in this baseline case will apply

across all additional scenarios. Subsequent analyses of the additional

scenarios will focus on how each case diverges from the baseline case, shedding

light on their unique elements.

To

achieve interoperability across organizations, the OASIS Open EMTC

recommends standardizing specific steps within the CAP alerting workflow. These

universal steps span the following sub-processes: observing, analyzing, originating,

and consuming. This guide aligns these steps with the use of events, event-types,

and event terms, as discussed in the OASIS Open Event Terms List

family of resources.

The

OASIS Open EMTC strongly advises CAP originators to include at least one

event code from the Event Terms List in every CAP message. This

practice ensures consistency and facilitates system interoperability. If no

exact match is found, the event-based framework described here still applies,

and the Users’ Guide offers instructions for maintaining

interoperability in such cases.

Lastly,

it’s important to recognize that this process applies to all alerting agencies

- public, private, and restricted alike. Whether alerts are broadly

disseminated (e.g., CAP <scope> = "public") or directed to

specific recipients (e.g., CAP <scope> = "private" or

"restricted"), the core process remains consistent .

Typical process for identifying an event-of-interest for the alerting

process:

1)

An

alerting agency observes an event situation , that involves one or more events,

with each event having the potential to lead an observer to devise and form an event-of-interest.

The agency gathers data about the events (using direct observation,

sensors, and predictive models), to help with the event-of-interest

determination. The event-of-interest is an abstract concept devised and formed from

the same observable conditions of the event’s nature, impacts, location and timing. The boundaries of each event-of-interest’s

conditions, may end up being a subset part of the event it is derived from .

a.

The events

involved are determined by the alerting business and typically pertain to those

that by policy, lead to an event-of-interest (and therefore a possible larger alerting

situation). The observed events ideally would be ones to have an associated event-type

on record.

b.

The

observation is conducted with a concerned client in mind (i.e., the

target audience in the larger alerting process). Ideally, the initial

observation for each event is carried out before any impacts to the client

occur, however, the observation activity is expected to continue throughout the

life of an event - before, during, and sometimes after the impacts for the

client are realized. Sometimes, the observation process begins after the event

has already impacted the audience.

c.

The

analysis stage, the stage following the observing stage, is when the full determination

of events-of-interest is made. If the analysis confirms the nature,

impact, location and timing are indeed interesting (either for the present or for

the future), an event-of-interest marker is applied to the event and the

observation stage continues until the event is no longer interesting.

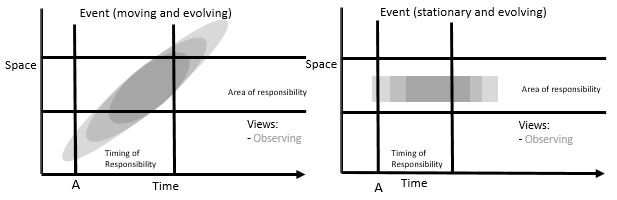

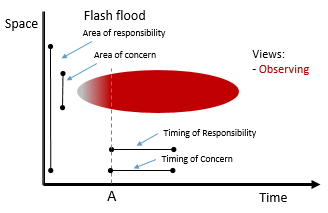

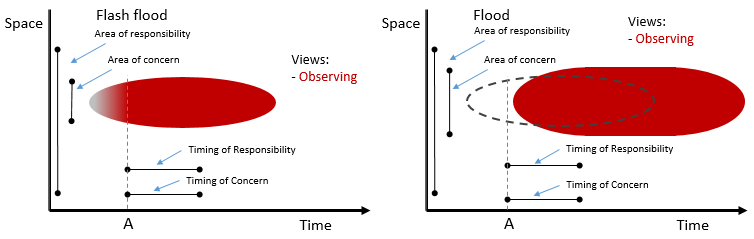

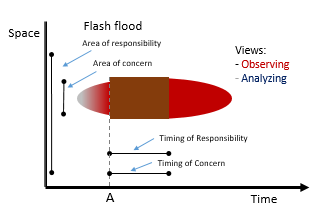

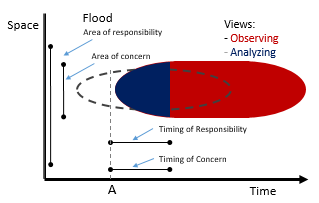

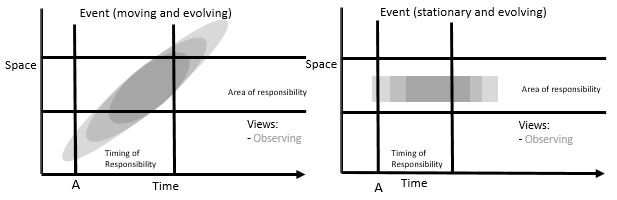

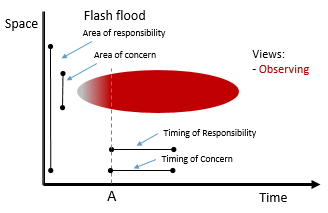

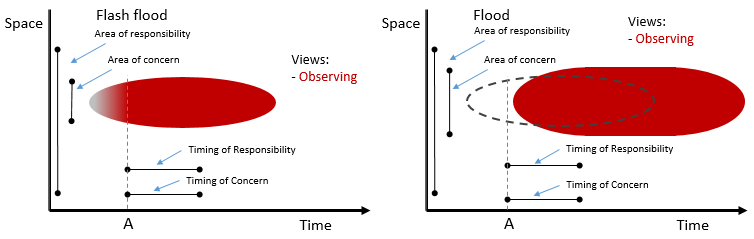

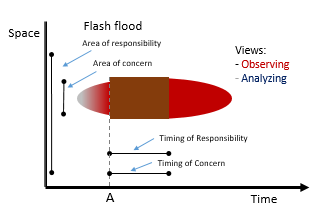

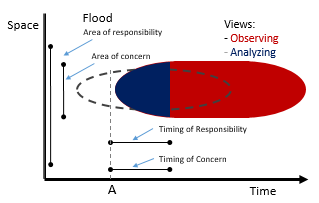

Background:

In the two diagrams below, two real events (both illustrated

in grey) are present at point-in-time A . One event is moving and

evolving, and the other is stationary and evolving . Point-in-time A serves

as the starting point for the observation exercise as in these two diagrams,

point-in-time A is when the observer became aware of the event. Note that the

events are shown as conceptual representations, without a defined scale for

space or time, and the two point-in-time A markers have no relationship to each

other in these illustrations – they represent separate cases.

In the two example cases, the nature, impacts,

location, and timing will meet or exceed the defined measures of significance (for

at least some measurable segment of time), as illustrated in the concentric

darker grey areas. The objective is simply to try and identify an observed

situation as containing a probable event-of-interest (subset or

otherwise), along with a general sense of the event-types involved.

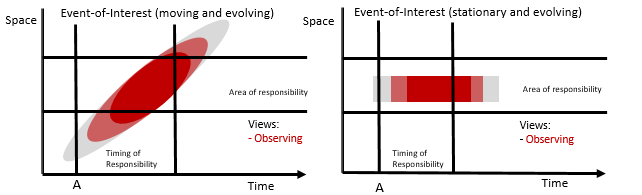

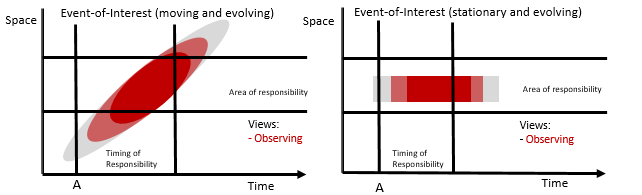

In the two illustrated example cases, the probable events-of-interest,

as per the observing process, are devised and formed as shown in red in the

diagrams below. They are probable, as the area in red is in the future (as of

point-in-time A). The leftover event areas shown in grey in the diagrams below,

are part of the observed events that do not meet the measure of nature and

impact of significant events, and therefore are not part of the probable events-of-interest.

There are now two events shown in each of the two diagrams,

the core event in grey and the event-of-interest in red. And

while they stem from the same event situation and comprise many of the same

conditions, they are treated as separate and distinct events, each with its own

devised and formed interpretation (two grey and two red).

All four interpretations are abstract constructs. Each

construct is based on a different set of bounding criteria which form each interpretation

. Additional interpretations,

the alert-worthy alerting event and the resulting alert message subject-event,

are discussed later in the analysis stage.

2)

For

any observed event within the situation, if the level of significance

for any one of the measures listed below is not close to being met (“close”

being a subjective assessment), the observed event may be excluded as a probable

event-of-interest and dismissed from further analysis .

a.

If the

nature of an event in the observed situation does not satisfy any

measure of conditional significance, the event may be dismissed (e.g., a wind event

situation being nothing more than a breeze).

b.

If the known impacts of

an event, based on its event-type, does not meet any measure of impact

significance, the event may be dismissed (e.g., a wind situation isolated to a

mountain peak. It may fall within an agency’s area and timing of responsibility,

however, it could still be outside the audience's area-of-concern due to

no actual audience present, resulting in no audience impact ).

c.

If the spatial location

of an event in the observed situation is not significant, the event may

be dismissed (e.g., an offshore storm moving away from any agency’s areas-of-responsibility).

d.

If the timing of an event

in the observed situation is not significant, the event may be dismissed (e.g.,

a distant storm that is not expected to reach the area of responsibility until much

later, well after the agency’s current timing-of-responsibility period).

i. If the event is a moving

event, and its most likely path is anticipated to bring it into the

area-of-responsibility at some far distant time, it would likely qualify as an event-of-interest,

however, not yet leading to an alert-worthy event. It remains under observation

until some future point-in-time when the situation changes .

3)

At the

current point in time, determine whether the events-of-interest are in a

real or imagined state . This is done while

acknowledging that any imagined state may not be realized, or may change to a

real state over time as new information becomes available.

4)

The monitoring range in

space for moving situations is likely much broader than

the range in space for stationary situations. For stationary situations, the

monitoring range would typically align with the alerting agency's area-of-responsibility.

5)

The monitoring range in

time for evolving situations is likely much longer than

the range in time for static situations. For static situations, the monitoring

range would typically align with the alerting agency's timing-of-responsibility.

6)

The

criteria for measuring the significance of an event-of-interest, based

solely on the nature of the events, are likely broader in scope than the

agency's criteria for an actual alert-worthy event (see next section).

The evolving and sometimes unpredictable nature of certain events could easily

transform a nearly alert-worthy event-of-interest into an actual

alert-worthy event-of-interest at a future time.

7)

The

alerting agency typically identifies a primary event within the observed

situation. This could be an individual event (e.g., a tornado) or a complex-event

event (e.g., a storm, composed of a wind event and a precipitation event) . This preliminary

assessment may change during the subsequent analysis stage.

8)

The

alerting agency should identify any secondary events within the observed

situation. If any secondary events are deemed events-of-interest, the situation

is tentatively classified as a complex-event situation. However, the

resulting larger alerting situation may still deal with the multiple

events-of-interest separately, a determination made in the analysis stage.

9)

The

alerting agency should identify risk or threat events that may

lead to one or more follow-on events-of-interest . These risk or threat events,

which are pre-existing and/or antecedent secondary events, form part of the

larger alerting situation surrounding a follow-on alert-worthy event. Pre-existing

or antecedent condition events are treated the same as other events and are also

classified as real or imagined based on their own nature .

10)

The

alerting agency may assign a label to the observed situation, such as a

name or an incident tracking identifier (e.g., a name like "Tropical Storm

Milton" or an identifier like "AAA-001," where "AAA"

represents the reporting entity's code and "001" is the incident

tracking number for that entity). This label assignment may also be applied

during the analysis stage.

11)

The

alerting agency may choose to record the observing-process event information in

a data object for post-analysis and future research. Such activities often help

identify improved methods for observing similar situations in the future.

Observing-process event information, with its wider leeway parameters, may

extend beyond the scope of the analyzing-process event information compiled

later.

Typical process for identifying alert-worthy events and subject events in

the alerting process:

1)

An alerting

agency analyzes the event data of an observed situation to determine if any

devised and formed events-of-interest are true events-of-interest – possibly

leading to the need for an alert-worthy event construct . The analysis would apply

to both the current and future states of an event-of-interest (as per the

standard practices of the alerting agency).

a.

Each potential

event-of-interest in the observed situation would be assessed against its own measures

of significance based on condition, impacts, location, and timing (as

outlined by the alerting agency’s policies based on event-type) .

i. For each potential event-of-interest

the alerting agency assesses the accuracy of the reported situation in

the observing process and validates or adjusts the reported conditions to a

final working assessment for the remainder of the analysis process.

2)

The

alerting agency analyzes the events-of-interest to determine any alert-worthy

events. Like events-of-interest, alert-worthy events are abstract

constructs - separate events devised and formed from the same observable

conditions. Each construct (event-of-interest and alert-worthy event) is based

on a different set of bounding criteria which form the event interpretations.

i. For each event-of-interest

the alerting agency compares the alerting agency area-of-responsibility

and timing-of-responsibility with the event-of-interest area and timing. An

analysis is completed to determine where and when the two areas and timings

intersect with each other. The intersection defines the interpretation of an alert-worthy

event (i.e. it creates the space and time boundaries of an alert-worthy event).

ii. If an event-of-interest is

determined to not be an alert-worthy event after analysis, it may still be

interesting, either as an associated secondary event to another alert-worthy

event, or as a possible future alert-worthy event. It may also be worth

commenting on in the larger alerting situation for the target audience of the

associated alert-worthy event.

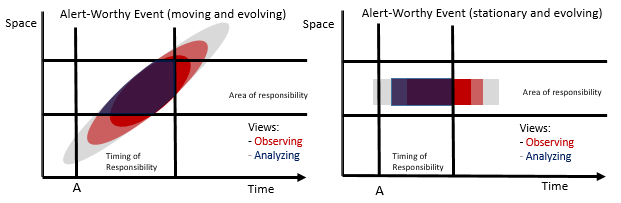

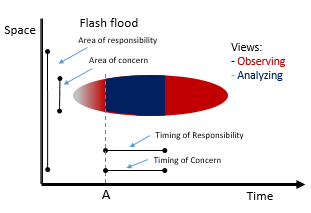

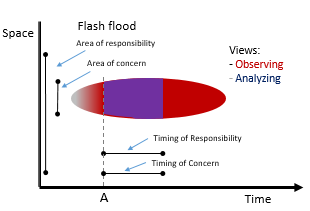

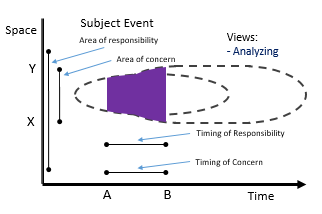

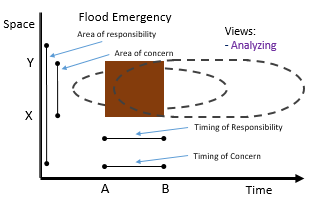

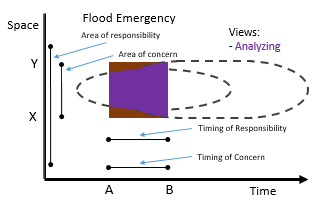

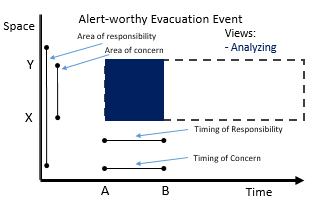

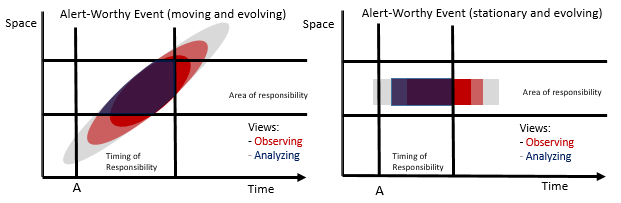

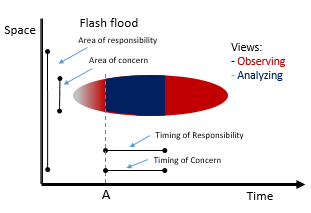

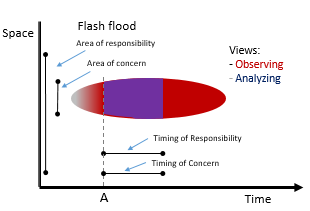

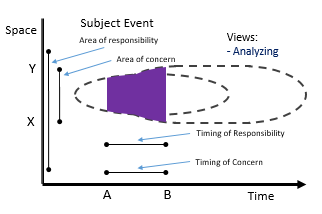

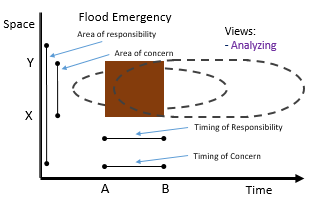

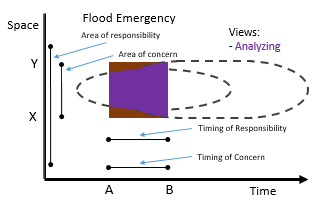

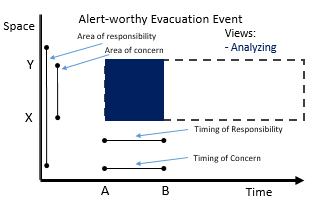

Background:

The diagrams below, using the same two real and

evolving events exampled in the observing process earlier, illustrate in blue

the alert-worthy space and time boundaries of concern for the two events.

In these examples, the alert-worthy event interpretation is a subset event of

the event-of-interest.

a.

For

each alert-worthy event the alerting agency determines the degree of significance

based on the nature of the event within the area and timing of responsibility.

b.

For

each alert-worthy event the alerting agency determines the degree of

significance based on impacts of the event within the area and timing of

responsibility[32].

3)

For

each event-of-interest, the alerting agency references the relevant history,

research, science, conventional wisdom, and policies from the event-type

for useable alert-worthy event based information (i.e. policies,

practices, procedures, etc.).

4)

If there

is more than one event-of-interest, the overall situation is a complex-event

situation. The alerting agency then is to decide how many alerting situations involving

alert-worthy events are actually contained within the overall situation .

a.

For

each alerting situation in the observed situation, the alerting agency

determines which alert-worthy events are to be part of which alerting situation.

b.

If two

or more alert-worthy events are placed into one alerting situation, then that

alerting situation is a complex-event alerting situation .

c.

Placing

one alert-worthy event into two or more alerting situations is also a

possibility and it is the purview of the alerting agency to do so, however, it

does presume that two or more co-existing alerting situations stemming from the

same alert-worthy event would not be providing contradictory information.

5)

Each

event-of-interest that becomes a primary alert-worthy event in one

alerting situation, could still be considered as a secondary event in another

alerting situation.

a.

As

part of the alerting situation, the alerting agency clarifies the primary

alert-worthy event and any associated secondary events-of-interests (e.g. a

secondary earthquake event-of-interest that a primary tsunami alert-worthy event

associates back to). The association can be made by standard alerting agency

policy (i.e. certain event types always associate with other event types, for

example, snow and cold), or can be made based on familiarity (i.e. certain

event types associate with each other based on the experiences of the agency

and its agents, for example, wind and electrical power grid outages) .

6)

Determining

an actual location in space and interval in time for the entire event (the grey

areas in the above diagram, including the red and blue area), is often

considered valuable information for parties that might have an interest in such

information. Such information is sometimes useful when telling the story as

part of the larger alerting situation to an audience. This would be at the

discretion of the alerting agency to decide whether to include it or not as

part of the story.

7)

During

the entire event-of-interest, if there is an oscillation (i.e. an ebb and flow

of an evolving event being in and out of significance), the decision on whether

to treat the observed situation as one or several event-of-interests is usually

a business policy decision. Often, such decisions derive from working backwards

from the alerting situation (e.g., knowing what the preferred outcome of the larger

alerting process is). This would be a consideration in the earlier analysis

process .

8)

Once

the compliment of alert-worthy events for each alerting situation has

been determined, the union of the alert-worthy events then becomes the subject-event

for the alerting situation. The subject event is another abstract construct – another

event-based definition devised and formed from the same set of observable

conditions.

a.

If the

entire event situation is a single event, the compliment of alert-worthy events

is only one event, thereby making the alert-worthy event and the subject-event

the same.

b.

For a complex-event

case, this may mean assigning some of the subject-event details from one

alert-worthy event and some of the details from another alert-worthy

event, or alternatively, having the details from one alert-worthy event

become proxies for the others .

9)

Alerting

agencies sometimes recognize that the space and time boundaries of an event-of-interest

are not measurable. If that is the case, the missing boundaries are not necessarily

a critical missing piece of the subject-event at this point. Location and

timing policies for alert-worthy events and subject events can be set by policy

to produce space and time boundaries for those constructs .

10)

Near

the end of the analysis stage, the alerting agency re-connects the subject-event

back to known event-types. The event types are likely the same as they were during

the observation stage, however, it could have changed based on the analysis of

the event situation and the larger alerting situation.

a.

The

analysis collectively includes the primary event-of-interest, the group

of associated secondary events-of-interest, and from experience, a general idea

of what the larger alerting situation for the target audience may end up being.

The re-connection back to event types can be formal (as part of alerting agency

policy), or informal (based on the experiences of the agency, community, and

their agents). Any secondary event-of-interests should be similarly re-connected

to their event types. Occasionally, during the analysis, a secondary event-of-interest

may take over as the primary event-of-interest.

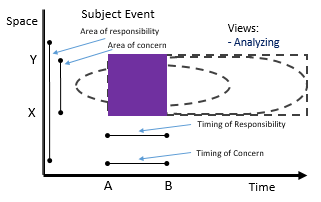

11)

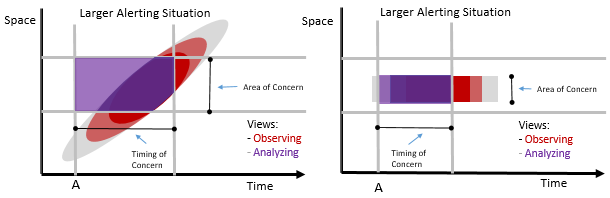

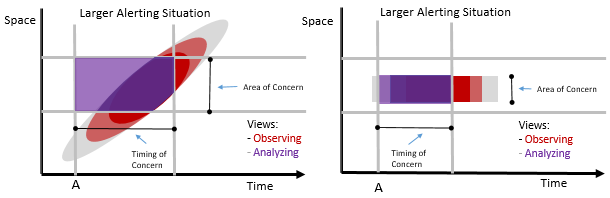

After

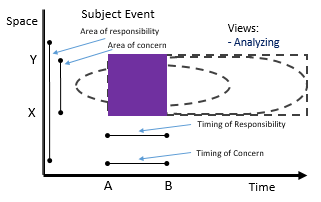

the alerting agency determines the make-up of the subject event, the

focus is on the larger alerting situation as it pertains to the

consuming audience (as shown in purple in the diagram below).

a.

If the

subject-event is an anticipated event (real or imagined), the larger alerting

situation will have a timing that includes lead timing, intersection timing,

and possible follow timing .

b.

If the

subject-event is underway within an area-of-concern, the larger alerting situation

will have no lead timing for some or part of the area, especially if the event is

a moving event. Past event information, while interesting, is outside of the

lead time period and is now just information for the larger audience story.

c.

Follow-timing

information is less often incorporated in the alerting story, however, it can

be important if follow-time impacts are expected. Follow-time situations, after

the alert-worthy event has ended, are typically used for extremely hazardous

event situations. Past information is common in follow-time alert messaging.

i. If the primary alert-worthy

event is ended (a real past event), and there are still follow time impacts

which linger, the larger alerting situation will have a timing that now includes

only follow-timing. The subject-event for the alerting situation now changes to

one of the follow time secondary events. That subject event would now have a

focus on a follow time alert-worthy event which would become the primary event

in follow time messages.

ii. The alerting situation may

still be considered the same alerting situation after the initial primary event

has ended (e.g. a “typhoon” alert-worthy event that has ended, however, a “typhoon

emergency” alert-worthy event remains - due to devastating and lasting impacts

of the recent typhoon).

1.

The alerting

agency might want to name the alerting situation a “typhoon emergency” from the

very beginning, anticipating follow-on messaging. This strategy connects

messages published before, during and after the typhoon emergency to a single

named event – supplying quick context to the follow time messaging.

12)

When the

subject-event is for a complex-event, then the larger alerting situation

is considered a complex-event alerting situation. In such cases, it is

recommended that the name of the larger alerting situation should represent the

“complex event” (i.e. a “storm” situation, when two “rain” and “wind” events

are combined to make up the complex event storm situation). Alternatively, if

two separate and distinct alerting situations are preferred by the alerting

agency (one wind, one rain), then this is a case of how the alerting process itself

can affect the overall situation analysis .

13)

The

alerting agency takes the additional details of the larger alerting situation

and reconciles these details with respect to a story they want to convey to their

alerting audience.

a.

Details

to reconcile with the larger alerting situation may be unique to the situation

and be introduced as a judgement call during the analysis (i.e. evacuation

routes that are normally used might be blocked due reasons outside of the

control of emergency responders).

b.

Details

may emerge from the larger situation involving proxies based on the

capabilities of the alerting process itself. Knowing the alerting process

capabilities, the construction of alert messages may be affected.

iii. The actual true location

of the subject event may not match with any pre-defined alerting zones used

by an agency. A true alert-worthy event location-mapping to alerting-zone

process may expand on the area, resulting in a larger alerting area than that

of the event-of-interest that triggered the alert (i.e. a case of over-alerting

the area-of-concern) .

iv. The actual true timing of

the larger

situation may

not match with the publishing timing of new alert messages. The alerting update

process typically is done based on the workload of front-line agents and often updates

or endings of an alert occur after portions of the audience are already free of

the impacts of the event-of-interest .

14)

The

alerting agency determines the name for an alert best suited to cover

the larger alerting situation. An alerting agency typically names an alert in

consideration of the alerting audience, trying for a short, accurate, descriptive

name for use in the any presentation of the alert messages (i.e. as used in

titles/headlines/etc.). Those alert names typically include a descriptor

involving the event type, however, that is not always the case .

a.

If any

associated event-of-interests and secondary events are to be covered within the

alerting situation, select a name for the alert that best covers the larger complex-event

situation.

15)

The

alerting agency constructs well suited alert message text for the larger alerting

situation. This would be based on the chosen subject-event part of the larger alerting

situation as well as any message text for each alert-worthy event that is included.

16)

The

alerting agency augments the alert message text from the previous step based on

the relevant compiled history, research, science, conventional wisdom, and

policies stored with the corresponding event types that make up the subject

event.

a.

Knowing

the primary event type for the subject event and the composition of the larger alerting

situation, the alerting agency checks the compiled history, research, science,

conventional wisdom, and business policies for helpful information on terms,

instructions, known impacts, call-to-action statements, codes, procedures, etc.

to include in the alert message.

17) If the larger alerting

situation is expected to change, or continue on past the current timing-of-responsibility

for the alerting agency, then a continuation of the alert is to be dealt with

using updated alert messages published at a later time. Knowing this, the focus

of the larger alerting situation can be weighted to the near future, leaving

the far future details for these later messages.

a.

These

later messages include ended messages (i.e. a CAP message type of “Cancel”

where the last mile presentation agency is instructed to discontinue the

alerting signal).

Typical process for originating a CAP alert message with event based

information:

The

process outlined here is typical for an agent on behalf of an alerting agency when

originating a CAP alert message. The OASIS Open EMTC recommends populating the subject-event

information and the larger alerting situation information into

CAP messages as per the following steps. The agent could either be an operator

entering alerting information into a CAP-based interface or a written program

that converts externally entered information into CAP-based alert messaging .

A CAP message revolves

around a subject event, which is a group of one or more alert-worthy

events, each with their event type. Without an event type, the alerting situation

addressed by the message would likely require a lengthier qualifying description,

demanding more time and effort than is typically ideal for an audience in the

consuming moment of concern. By introducing the event through an associated

event type (e.g., using a headline or other mechanism), an alerting agency can

convey the importance or significance of a subject event quickly and

efficiently. The full details of the actual alerting situation can then be subsequently

shared with an audience that is already engaged as a result of consuming the

headline. The event types used in this messaging process are derived from the

earlier analysis stage that has already been completed.

The alerting agency

initiates a process to originate a valid CAP file. The CAP elements outlined

below are linked to the event or event types in a CAP alert message.

1)

Element:

<event> cap.alertInfo.event.text (required).

This is a basic element that is required in CAP. A CAP

message with no <event> element is an invalid CAP message.

Definition (CAP v1.2): The text denoting the

type of subject-event of the alert message.

Objective: The objective of the <event>

element is to assist consuming agencies in clearly communicating to their audiences

the type of event associated to the subject-event in messages published by the

CAP alerting agency.

b.

With the

expectation of well-crafted text, as per the social science of the situation, the

<event> element’s value is designed to provide immediate context to

an audience the reason for the alert message. The text should generate an

association to a familiar type of event for the audience. Audiences are then prepared

to receive, with context, the remaining message information that follows.

c.

The

<event> element is a display-based, audience-facing element

composed of free-form text. It is designed in CAP to be a fully flexible

element, capable of delivering event-type information to any audience without

the limitation of pre-published values. As an audience-facing element, the

meaning of the value is only constrained to the operating language of the

alerting service, not to any functional language between agents executing the

service.

i. The <event>

element is often constrained within an alerting service to pre-set values (as

pre-set values are a sub-set of all possible values), however, the decision to

do so risks affecting the ability of alerting agencies to adjust to unexpected

situations and/or adapt to changes moving forward when constrained to a formalized

change process.

1.

New

event types are typically discovered as they are happening. Change process

delays, due to new configuration and partner coordination, may impact the

ability to provide a timely service for new event types if only pre-set values

are used. The ability to add new types quickly is highly recommended in any

alerting service.

2.

The OASIS

Open EMTC recommends, that originating agencies that employ a set of

enumerated event-types that provide pre-set values for the <event>

text element, should make it clear:

a.

that the

names associated to the event-types are for display purposes and could

change without notice; and

b.

that

consuming agents and agencies wishing to automate processing functions (based

on the <event> element), should use other CAP elements, including

the agency’s compliment of <eventCode> elements .

d.

The

originating agency expects the <event> value to be either

displayed as provided (e.g., <event>); used within a constructed

presentation that incorporates the value (e.g., "Event type:

<event>"), or omitted in favor of alternative elements such as

<headline>, or other presentation constructs derived from the <eventCode>

element (e.g., icons or symbols).

e.

The

alerting agency should construct the <event> element in a CAP

message using an attribute of the event-type that describes the

event-type by name. This name attribute should be defined as free-form text,

reflecting the alerting agency’s local terminology in accordance with the

operating language of the alerting service. The selected value should take into

account the perspective of the target audience.

i. The <event>

element is not used to describe an actual event; rather, it is populated to

indicate a type of event. For example, the <event> element would be

assigned <event>hurricane</event> (an event-type

name) rather than <event>hurricane Katrina</event> (the

name of a specific event).

f.

If no acceptable

event-type name is available locally, a term may be entered manually if the local

process allows. The entered term would be expected to be displayed by consuming

agencies as given. Alternatively, the originating agency may also check the OASIS

Open Event Terms List – Lookup Table to find an event-type term that aligns

with the local event-type’s meaning and understanding. Note that since the OASIS

Open Event Terms List is not translated into other languages, any necessary

translations should have been completed in advance and stored as part of the event-type

information.

g.

If no

exact match is found in the OASIS Open Event Terms List, a close acceptable match

may be selected. Suitable alternatives include:

i. variations of the same

term (e.g. “flood”, “floods”, “flooding”), or

ii. synonymous terms (e.g. “tropical

storm” and “tropical cyclone”), or

iii. a more general term that

serves as an acceptable proxy for a more specific term along the

general-to-specific spectrum (e.g., "wind" as a broader term for

"small craft wind") , or

iv. a best judgement call.

h.

If no

close acceptable match is found in the OASIS Open Event Terms List, then

the event term “other” should be the OASIS Open term identified for use . The use would be for the

<eventCode> element as discussed below, not for the <event>

element discussed here. The <event> element would be populated as

discussed above in the previous sub section.

i. For alerting originators,

using “other” for the <eventCode> element means the matching process

was attempted, however, nothing acceptable was found. This outcome is preferred

as compared to the outcome where the matching process gives the impression of a

step ot being attempted at all. The term “other” is an interoperability

requirement allowing consumers some recourse of action when “other” is

encountered as an <eventCode> – see the following CAP Consuming

process section below.

ii. The term “other” in the

<event> value is not prohibited; it’s typically considered meaningless

for most presentation systems and therefore is not recommended.

iii. If "other" is found

as a match, the OASIS Open EMTC recommends that the alerting agency

consider submitting a new event term for review. This term would replace

"other" in future instances of the currently unmatched event-type for

the local alerting agency. The submission process is outlined in the section on

Submitting Content in the OASIS Open Event Terms List – Lookup Table.

i.

If any

associated events-of-interest are identified, and are to be handled

collectively as one complex-event, the <event> element

value should represent the broader event situation as a whole. For example, instead

of specifying a narrower event such as <event>power grid

failure</event>, a more encompassing event term like <event>service

interruption</event> could be used instead .

i. Continuing with the complex-event

example, if the overall complex-event situation is deemed as a group the primary

event-of-interest, the complex-event becomes the event that anchors the larger

alerting situation. The individual events-of-interest that make up the

complex-event may or may not be explicitly addressed as part of this larger

situation. If the agency so chooses to address any of the individual

events-of-interest, the CAP standard allows for this to be part of the <discussion>

element (for target audiences), and as part of the <eventCode> element

(for processing agents. See <eventCode> element below). Consequently,

the alerting agency may assign the primary event-of-interest to be the

complex-event knowing that this messaging option is available for all the

individual events-of-interest in CAP .

2)

Element:

<eventCode> cap.alertInfo.eventCode.group (optional).

This is an added element that is optional in CAP. A CAP

message with no <eventCode> element is still valid CAP.

Definition (CAP v1.2): A system-specific code

identifying an event-type for the alert message.

Objective: The objective of the <eventCode>

group is to assist consuming agents when making processing decisions based on

the type of event that the originating agents designate as the subject event

for the alert messages.

a.

Sub-element:

<eventCode>.<valueName> cap.alertInfo.eventCode.valueName.text

(required).

This is a conditionally required

element in CAP. An <eventCode> element group in CAP with no

<valueName> sub-element is an invalid group.

Objective: The objective of the <eventCode>.<valueName>

element is to reference the managed set of event-type codes in use when

populating the corresponding <eventCode>.<value>

element within the group.

b.

Sub-element:

<eventCode>.<value>

cap.alertInfo.eventCode.value.code

(required).

This is a conditionally required

element in CAP. An <eventCode> element group in CAP with no

<value> sub-element is an invalid group.

Objective: The objective of the <eventCode>.<value>

element is to indicate to the consumer of the CAP message the chosen code in

use within the group. The value is from the referenced <eventCode>.<valueName>

set of event-type codes.

c.

The <eventCode>

group element is defined as a multi-instanced group element in a CAP message . The alerting agency may optionally

build none, one, or several <eventCode> element groups in a CAP

message using values from one or several sets of standardized and managed event

codes.

i. In a zero instance case,

with no <eventCode> group element, the OASIS Open EMTC

recommends that such a case be best left for closed systems where the

originator and consumer are both part of the same closed system. In open

systems, where the originator and consumer are often unknown to each other, the

zero case still allows for consuming system processing, however, it often leads

to simpler presentations without any event-based controls. Consuming systems

may interrogate less reliable elements for clues about the event-type, such as

the loosely defined <event> element, however, the OASIS Open

EMTC considers the results to be less reliable.

ii. In a single instance case,

with only one <eventCode> group element, the originating systems

would be limiting the advantage of the <eventCode> element to

consumers that use the referenced event-type set. The OASIS Open EMTC

recommends that in the single instance case, the set referenced is the OASIS

Open Event Terms List.

iii. In a multi-instanced case,

with two or more <eventCode> group elements, the elements within

each group are each considered independent groups to processed separately.

There may be single codes from two or more referenced sets of event codes, or

multiple codes from a single referenced set of event codes, or, if the

situation suggests, multiple codes from several referenced sets .

d.

If

there is a complex-event situation, the OASIS Open EMTC recommends that

for maximum flexibility of all consuming agents, all the applicable codes from

all the referenced sets in use by the agency be added to the CAP message . In such cases, the OASIS Open EMTC recommends listing the primary

event-of-interest type first.

e.

The

<eventCode>.<value> may be displayed by consuming

agencies as provided or incorporated into a presentation that includes the

value (e.g. “Event code: <eventCode>.<value>”). However,

it is considered a value primarily designed for agents along the path of

distribution to make decisions rather than for direct presentation to the final

audience.

i.

If the

target audience is emergency services personnel responding to the alert message

by providing follow-on services, the <eventCode>.<value>

itself may hold significance in that presentation.

3)

Element:

<category>: cap.alertInfo.category.code (required).

This

is a basic element that is required in CAP. A CAP message with no <category>

element is an invalid CAP message.

Definition (CAP v1.2): The code denoting the category (or categories) of

the subject event of the alert message.

Objective: The objective of the <category>

element is to assist consuming agents in making clear processing decisions

based on one or more standard CAP <category> values. These values

are selected from an enumerated set of allowable options as defined by the CAP

standard for this element.

a.

With

the expectation that categories are appropriately assigned based on the event

situation, the <category> element’s value is intended to provide

immediate filtering context for consuming agents. This helps them process or

redirect the message effectively along the path of distribution.

b.

The

<category> element is designed as a multi-instance element within

a CAP message. The alerting agency has the option to include one or more <category>

elements as needed.

i. In cases where only a

single instance of the <category> element is used, despite the

situation containing multiple applicable options, the originating systems may

be restricting the intended advantage of the <category> element as

defined.

ii. In a multi-instance

scenario where two or more <category> elements are included, each

value is treated as an independent entity to be processed separately. The OASIS

Open EMTC recommends adopting the multiple <category> approach

to maximize flexibility for consuming agents .

c.

If a

complex-event situation involves multiple event types, multiple <category>

instances should be used to list all relevant categories contributing to the

broader situation. When multiple <category> groups are necessary,

the OASIS Open EMTC recommends listing the primary

event-of-interest categories first .

d.

A

default set of one or more associated CAP <category> values should

be pre-assigned for all business event-types during the research and

science stage of event-type development. These values should be filed as

part of the event-type information. The OASIS Open EMTC advises against

selecting event-type CAP <category> values during the alerting process

(i.e. on the fly), as this approach may lead to varied interpretations among

agents and clients, potentially compromising the integrity of the agency’s

alerting service over time.

i. The <category>

element is determined locally by selecting one or more enumerated values from

the CAP standard or choosing matching event-term entries from the OASIS Open

Event Terms List .

ii. One option is to include

all categories as listed in the mapping. However, since the OASIS Open Event

Terms List – Lookup Table is also accessible to consuming agents, they can

independently use the given <eventCode> value to look up all OASIS

Open assigned CAP <category> values if they choose to do so.

iii. Consuming agencies, along

with their clients, can establish customized arrangements to incorporate a CAP

category into their partnership, ensuring clients receive services tailored to

their preferences. For example, an agency may choose to add the CAP category

"Safety" to an OASIS Open event term, even if OASIS Open

does not include "Safety" among its listed mappings .

iv. If an acceptable entry in

the OASIS Open Event Terms List is matched, but no suitable CAP category

is available (in the opinion of the alerting agency), the agency may still

select other CAP Category values from the CAP standard. Additionally, the

agency should consider submitting a new CAP category to the OASIS Open EMTC

for review to accompany the identified OASIS Open event term .

4) Element: <headline>: cap.alertInfo.headline

(optional).

This

is an added element that is optional in CAP. A CAP message with no <headline>

element is still valid CAP.

Definition

(CAP v1.2): The text headline of the alert message.

Objective: The objective of the <headline>

element is to assist consuming agents in introducing the alert message to

audiences. It provides a brief, concise summary with the most relevant details

to ensure quick comprehension.

a.

The

alerting agency should construct the CAP <headline> element, as

well as other audience-facing text-based CAP message elements (e.g., <description>

and <instruction>), using their local event term naming label (in

their operating language), to represent the broader event-type situation.

Additionally, any relevant details from the larger alerting situation that

enhance clarity may be included in a concise, attention-grabbing statement. The

<headline> should motivate the audience to explore the full alert message

for further information.

5) Element: <onset>: cap.alertInfo.onset

(optional).

This

is an added element that is optional in CAP. A CAP message with no <onset>

element is still valid CAP.

Definition (CAP v1.2): The expected time of the beginning of the subject

event of the alert message.

Objective: The objective of the <onset>

element is to assist consuming agents in communicating the expected start time

of the subject-event within the area-of-concern to audiences.

a.

If the

subject-event's beginning time is unknown, or is quite varied across the

area-of-concern, the <onset> element may be omitted from the CAP

message. In such cases, the <discussion> element can be used to

provide a descriptive explanation of the expected start time as appropriate for

the situation.

b.

If the

subject-event involves a risk or threat event that could lead to a possible

event-of-interest in the area-of-concern, the OASIS Open EMTC recommends

omitting the optional <onset> element from the CAP message.

Including the onset of the risk event could mistakenly be interpreted as the

onset of the actual event-of-interest that the risk event is attempting to

reference[58].

6)

Element:

<parameter>: cap.alertInfo.parameter.group (optional).

This

is an added element that is optional in CAP. A CAP message with no <parameter>

element is still valid CAP.

Definition (CAP v1.2): A system-specific additional parameter associated

with the alert message.

Objective: The objective of the <parameter>

group element is to assist consuming agents in processing additional,

non-standardized alert message information that originating agencies wish to

convey. This additional information may be event-based or event-type-based

and can serve either as display-based, audience-facing content or as decision-based,

agent-facing data - or both[59].

a.

Sub-element:

<parameter>.<valueName> cap.alertInfo.parameter.valueName.text

(required).

This is a conditionally required

element in CAP. An <parameter> element group in CAP with no

<valueName> sub-element is an invalid group.

Objective: The objective of the <parameter>.<valueName>

element is to provide an assigned naming reference for the information

contained in the corresponding <parameter>.<value>

element within the group.

b.

Sub-element:

<parameter><value>

cap.alertInfo.parameter.value.text

(required).

This is a conditionally required

element in CAP. A <parameter> element group in CAP with no

<value> sub-element is an invalid group.

Objective: The objective of the <parameter>.<value>

element is to indicate to the consumer of the CAP message the chosen value for

the additional, non-standardized alert message information within the group.

c.

The <parameter>

group element is defined as a multi-instanced group element in a CAP message.

The alerting agency may optionally build none, one, or several <parameter>

element groups in a CAP message providing values for as many additional,

non-standardized alert message pieces of information as desired.

7)

Element:

<effective> cap.alertInfo.effective.time (optional).

This

is an added element that is optional in CAP. A CAP message with no <effective>

element is still valid CAP.

Definition (CAP v1.2): The effective time of the information of the

alert message.

Objective:

The

objective of the <effective> element is to assist consuming agents

in determining when the presentation of the information within the alert message

should begin. The begin time is derived from the broader event situation, which

in turn in turn is composed of the subject event and, if applicable, its lead

time[60].

a.

If the

alert message is intended for presentation to an audience at a future time,

that moment marks when the originating agency seeks to initiate audience awareness

of the subject event. Such larger alerting situations are primarily used for

distant future events, where the beginning of the lead time period itself falls

to a future point in time .

b.

If the

preferred <effective> time for the alerting agency has already

passed, the <effective> element may be omitted from the CAP

message, as the effective time would then be equivalent to the message's

publish time. This is a common practice for update CAP messages when the subject-event

is already having an impact.

8)

Element:

<expires> cap.alertInfo.expires.time (optional).

This

is an added element that is optional in CAP. A CAP message with no <expires>

element is still valid CAP.

Definition (CAP v1.2): The expires time of the information of the alert

message.

Objective:

The

objective of the <expires> element is to assist consuming agents

in determining when the presentation of the information within the alert message

should conclude. The end time is typically based on the broader event

situation, which in turn is composed of the subject event and, if applicable,

its follow time .

a.

The

alerting agency fills in the optional <expires> element with

either the anticipated end time of the larger alerting situation or the end

time of the agency’s current period of responsibility (at the time of

publishing). This includes if the larger event situation extends beyond that expires

point. Typically, for short-duration events, the overall situation's end time

aligns with the conclusion of the event-of-interest.

b.

The

CAP standard permits the <expires> element to be optionally

omitted from the CAP message. However, the OASIS Open EMTC recommends

including the <expires> element and assigning a value based on an

alerting business policy - typically the current end time of the alerting

agency’s timing-of-responsibility, as determined at the time of publishing .

i. The <expires>

element is optional, but its absence can be concerning for consuming agents, as

there is no formal directive specifying when the message presentation should

end. In such cases, consuming agents must assume that the originator will

eventually provide a follow-up update or cancellation message within a

reasonable timeframe to address the expiration timing of the alerting signal.

ii. When an <expires>

time is absent, consumers must assume that no network or system issue will

disrupt the delivery of a follow-up message through the distribution path. To

avoid appearing delinquent in the alerting process (by not removing the message

presentation in a timely manner), consuming agencies and agents generally

prefer originators to include an upfront <expires> element in all

CAP messages . The OASIS Open EMTC

recommends that the <expires> element always be present and

assigned a reasonable end time for message presentation.

iii. Originators concerned

about the potential for alert messages to expire on consuming systems, before a

replacement message arrives to supersede the message, should factor in a reasonable

buffer time beyond the true expires time for the message information. This

would be a value balanced by the alerting agency recognizing the consuming

agencies desire to not have expired information be presented well after the

message, and its information, has gone stale .

9)

Element:

<incidents> cap.alert.incidents.group (optional).

This

is an added element that is optional in CAP. A CAP message with no <incidents>

element is still valid CAP.

Definition (CAP v1.2): The “group listing” naming the referent

incident(s) of the alert message.

Objective: The objective of the <incidents>

element in a CAP message is to link the current alert message to a broader

observed situation identified by a name and/or index. An alerting agency may

optionally include an <incidents> element for cross-referencing

and tracking purposes, assisting consumers in understanding the context (e.g.,

a named event like "Hurricane Katrina"). Identifiers may take the

form of incident tracking codes assigned by different reporting agencies (e.g.,

AAA-001, BBB-007), allowing multiple agencies to cross-reference their incident

records .

a.

The

incident naming or incident indexing practice is determined by the alerting

agency as part of its organizational profile. Consumers of the originating agency’s

CAP messaging can then utilize the assigned value for tracking and

cross-referencing purposes.

b.

International

naming and indexing activities for extreme events (e.g., earthquakes,

volcanoes, etc.) are among the tracking considerations an alerting agency may

take into account when utilizing the <incidents> element.

The following element(s)

(including sub-elements) outline additional OASIS Open EMTC recommendations for

improving interoperability in Common Alerting Protocol (CAP) across digitally

connected systems and are applicable to the event and event-type aspects of the

alerting process.

10) Element: <code> cap.alert.code.code

(optional).

This

is an added element that is optional in CAP. A CAP message with no <code>

element is still valid CAP.

Definition

(CAP v1.2): A code denoting special handling of the alert message.

Objective: The objective of the <code>

element is to assist consuming agencies in processing special handling

information that may be included in a CAP message.

a.

Special

handling information refers to details that go beyond the standard alerting

data in a CAP message. This may include additional information layers or

constrained elements as part of a profiled limitation (e.g., a maximum length

for a free-form text value). Some consumers may choose to ignore special

handling information so originators should treat <code> as an element

that may not be relevant to all recipients. For example, a size limitation not

relevant to a consumer, but indicated by an originator, can easily be ignored

by the consumer.

b.

The <code>

element is defined as a multi-instanced element in a CAP message.

i. The OASIS Open EMTC

recommends that alerting agencies utilizing the OASIS Open Event Terms List

populate at least one <code> element with the following value, as

defined by OASIS Open :

<code>layer:OASIS-Open:ETL-LT:v2.0</code>.

1.

The OASIS

Open EMTC classifies the Event Terms List as a layer and

specifies that the term "layer" must be included, as

demonstrated in the example.

2.

The OASIS

Open EMTC prefers the use of a hyphen to fill in blank spaces in its name

for the <code> element and specifies that “OASIS-Open” be

the form of the name, as per the example, not “OASIS Open”.

3.

The OASIS

Open EMTC defines versions for the list and specifies that the version

reference “v2.0” be included, as per the example.

c.

Omitting

or ignoring a <code> element does not negatively impact the CAP