The key words “MUST”, “MUST NOT”, “REQUIRED”, “SHALL”, “SHALL

NOT”, “SHOULD”, “SHOULD NOT”, “RECOMMENDED”, “MAY”, and “OPTIONAL” in this

document are to be interpreted as described in [RFC2119].

·

[RFC2119] Bradner, S., “Key

words for use in RFCs to Indicate Requirement Levels”, BCP 14, RFC 2119, March

1997. http://www.ietf.org/rfc/rfc2119.txt.

·

[Alexander 1964] C. Alexander, Notes

on the Synthesis of Form, Harvard University Press, 1964

·

[Alexander 1979] C. Alexander, The

Timeless Way of Building, Oxford University Press, 1979

·

[Brown 2011] P. Brown, Introducing

Pattern Languages, March 2011 http://www.peterfbrown.com/Documents/Introducing%20Pattern%20Languages.pdf

·

[BSI-SCF] Smart City Framework – Guidance for decision-makers in smart cities

and communities, [January 2014]

·

[Coplien 1996] J. O. Coplien, Software

Patterns, Bell Laboratories, The Hillside Group 1996

·

[EIF] The European

Interoperability Framework, version 2, European Commission 2010, Annex 2 of

http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2010:0744:FIN:EN:PDF

·

[OIX] Open Identity

Exchange, http://openidentityexchange.org/

·

[SFIA] The Skills Framework for

the Information Age, SFIA Foundation, http://www.sfia-online.org

·

[SOA-RAF] The SOA Reference Architecture

Framework, OASIS, http://docs.oasis-open.org/soa-rm/soa-ra/v1.0/cs01/soa-ra-v1.0-cs01.pdf

·

[SOA-RM] The Reference Model for

Service-Oriented Architecture, OASIS, http://docs.oasis-open.org/soa-rm/v1.0/

·

[PMRM] The Privacy Management

Reference Model, OASIS, http://docs.oasis-open.org/pmrm/PMRM/v1.0/csd01/PMRM-v1.0-csd01.html

Summary

The Transformational Government Framework (TGF)

is a practical “how to” standard for the design and implementation of an

effective program of technology-enabled change at national, state or local

government level. It describes a managed, customer-centred process of

ICT-enabled change within the public sector and in its relationships with the

private and voluntary sectors, which puts the needs of citizens and businesses

at the heart of that process and which achieves significant and

transformational impacts on the efficiency and effectiveness of government.

Context

All around the world, governments at national, state, and

local levels face huge pressure to do “more with less”. Whether their desire is:

to raise educational standards to meet the needs of a global knowledge economy;

to help our economies adjust to financial upheaval; to lift the world out of

poverty when more than a billion people still live on less than a dollar a day;

to facilitate the transition to a sustainable, inclusive, low-carbon society;

to reduce taxation; or to cut back on public administration; every government

faces the challenge of achieving their policy goals in a climate of increasing

public expenditure restrictions.

Responding effectively to these challenges will mean that governments

need to deliver change which is transformational rather than incremental.

During much of the last two decades, technology was heralded

as providing the key to deliver these transformations. Now that virtually every

government is an "e‑Government" - with websites, e‑services

and e‑Government strategies proliferating around the world, even in the

least economically developed countries - it is now clear that Information and

Communication Technologies (ICT) are no “silver bullet”. The reality of many

countries' experience of e‑Government has instead been duplication of ICT

expenditure, wasted resources, no critical mass of users for online services,

and limited impact on core public policy objectives.

An increasing number of governments and institutions are now

starting to address the much broader and more complex set of cultural and

organizational changes which are needed if ICT is to deliver significant

benefits in the public sector. We call this process: Transformational

Government.

Definition of Transformational

Government

The definition of Transformational Government used in the

Framework is:

Transformational Government

A managed, customer-centred, process of ICT-enabled change within

the public sector and in its relationships with the private and voluntary

sectors, which puts the needs of citizens and businesses at the heart of that

process and which achieves significant and transformational impacts on the

efficiency and effectiveness of government.

This definition deliberately avoids describing some perfect “end-state”

for government. That is not the intent of the Transformational Government

Framework. All governments are different: the historical,

cultural, political, economic, social and demographic context within which each

government operates is different, as is the legacy of business processes and

technology implementation from which it starts. So the Transformational

Government Framework is not a “one-size-fits-all” prescription for what a

government should look like in future.

Rather, the focus is on the process

of transformation: how a government can build a new way of working which

enables it rapidly and efficiently to adapt to changing citizen needs and

emerging political and market priorities. In the words of one of the earliest

governments to commit to a transformational approach: “…. the vision is not

just about transforming government through technology. It is also about making

government transformational through the use of technology”,

Target audience for the

Transformational Government Framework

The Transformational Government Framework (TGF) is intended

primarily to meet the needs of:

-

Political and administrative leaders responsible for shaping

public sector reform and e‑Government strategies and policies (at

national, state/regional and city/local levels).

-

Senior executives in industry who wish to partner with and assist

governments in the transformation of public services and to ensure that the

technologies and services which the private sector provides can have optimum

impact in terms of meeting public policy objectives.

-

Service and technology solution providers to the public sector.

Secondary audiences for the Transformational Government

Framework include:

-

Leaders of international organizations working to improve public

sector delivery, whether at a global level (e.g. World Bank, United Nations) or

a regional one (e.g. European Commission, ASEAN,

IADB).

-

Professional bodies that support industry sectors by the

development and maintenance of common practices, protocols, processes and

standards to facilitate the production and operation of services and systems

within the sector, where the sector needs to interact with government processes

and systems.

-

Academic and other researchers working in the field of public

sector reform.

-

Civil society institutions engaged in debate on how technology

can better enable service transformation.

Structure of the Transformational

Government Framework

The TGF can be seen

schematically in Figure 1. At the top-level, it is made up of the following

components:

·

guiding principles: a statement of values which leaders can use to steer

business decision-making as they seek to implement a TGF program;

·

guidance

on the

three major governance and delivery processes which need to be refocused in a

customer-centric way, and at whole-of-government level, in order to deliver

genuinely transformational impact:

-

business management,

-

service management, and

-

technology and digital assets management

based on the principles of service-oriented architecture.

·

benefit realization: guidance on how to ensure that the intended benefits of a TGF program are

clearly articulated, measured, managed, delivered and evaluated in practice;

·

critical success

factors: a checklist of issues which TGF programs should regularly monitor

to ensure that they are on track for successful delivery and that they are

managing the major strategic risks effectively.

Figure 1: The overall TGF framework

Each of these six components is described in detail in the

following sections, which set out the activities which a TGF program should

undertake in each area in order to be successful. These activities

(highlighted in pink in Figure 1) are expressed in a formal structure as a set

of “patterns languages”. This set of patterns is intended to be readable

end-to-end as a piece of prose but is structured also in a way that lends

itself to being quoted and used pattern by pattern and to being encapsulated in

more formal, tractable, and machine-processable forms including concept maps,

Topic Maps, RDF or OWL.

Pattern Languages

The idea of Pattern Languages, as a process for analyzing

recurrent problems and a mechanism for capturing those problems and archetypal

solutions, was first outlined by architect Christopher Alexander [Alexander

1964] and [Alexander 1979]: “The value of a Pattern Language is that

remains readable and engaging whilst providing basic hooks for further machine

processing… [it] is not an ‘out-of-the-box’ solution but rather some ‘familiar’

patterns with which a team can work” [Brown 2011].

The exact configuration

varies from one pattern language to another, and the pattern adopted in the TGF

is structured as follows:

·

the name of the pattern and a reference number;

·

an introduction that sets the context and,

optionally, indicates how the pattern contributes to a larger pattern;

·

a headline statement that captures the essence of the need

being addressed;

·

the body of the need being addressed;

·

the recommended solution – what needs to be done;

·

some notes on linkages, showing how each pattern links to

related and more detailed patterns that further implement or extend the current

pattern. In some cases this also includes references to external resources that

are not part of the TGF.

These patterns together make up an initial set of “Core

Patterns” of what is expected to be an evolving set of TGF patterns. These

form the core of the TGF standard, and it is against these that conformance

criteria are set out in Section 9. Where closely related patterns have been

grouped together in one section of this document – for example, on Business

Management, Service Management and Technology and Digital Asset Management –

the relevant section also includes some additional introductory text to help

readers understand linkages more easily. This text, however, does not form

part of the TGF Core Pattern Language.

There is one TGF Core Pattern on Guiding Principles. This

is set out below.

Context

Development and delivery of a

successful TGF program requires collaboration and change across a wide range of

individuals, communities and organizations over a sustained period of time. An

approach that is rooted in a set of clearly stated principles can help ensure

that business decisions across those organizations align.

In the TGF, we use the term “principle” to mean an enduring

statement of values which can used on a consistent basis to steer business

decision by multiple stakeholders making over the long term, and which are:

·

used

to inform and underpin strategy;

·

understood, agreed and owned by stakeholders.

v v

v

The Problem

A management hand on the

tiller is not enough to deliver effective transformation. Effective

transformational government strategies need to be principle-based.

“Transformational Government” is a managed process of

ICT-enabled change in the public sector, which puts the needs of citizens and

businesses at the heart of that process and which achieves significant and

transformational impacts on the efficiency and effectiveness of government. Leaders

of TGF programs face significant challenges. These include:

·

the scope of the program, which

touches on a very wide range – potentially all – social and economic activity

in a jurisdiction;

·

the scale of ambition for the

program, which is aiming to achieve change that is transformational not

incremental;

·

the wide range of stakeholders and

delivery partners involved in the program.

Taken together, these

challenges mean that top-down change management approaches cannot work. Success

cannot be delivered by planning in detail all elements of the change at the

outset. Rather, it can be delivered by setting out a clear and agreed vision,

and then underpinning this with a roadmap that does not over-plan but that

provides a framework for an organic, inclusive process of change to deliver the

vision over time across multiple stakeholders. Key elements of this are

explored in the other Patterns of the TGF. But the starting point should be

clarity about the guiding principles that stakeholders will seek to work

towards throughout this process.

A “one-size-fits-all” approach to public sector reform does not

work. Nevertheless, there are some guiding principles which 10-15 years of experience

with e‑enabled government around the world suggests are universal. They

are based on the experience of many OASIS member organizations working with

governments of all kinds, all around the world, and they form the heart of the TGF.

v v

v

The Solution

TGF leaders should

collaborate with stakeholders to develop and agree a set of guiding principles

for that specific TGF program that cover, as a minimum, the core TGF Guiding

Principles.

The TGF Guiding Principles are

set out below, and must be used by any Transformational Government program

conforming to the Framework. These principles together represent an enduring

statement of values which the Leadership for a Transformational

Government program should adopt and use consistently as a basis to steer

business decision-making throughout the conception, development, implementation

and follow-up of that program. These are explicitly declaratory

statements of principle (“We believe…”) that reflect the desired commitment of

the program Leadership as well as indicating the expectations from all Stakeholders.

We believe in establishing a

vision of the future which our TGF program will create which is clear,

compelling and jointly owned by all stakeholders

Clarity

about the social, economic and environmental outcomes we want to achieve, and

the challenges involved in doing so.

A

shared vision of how we will invest in and transform our physical, spatial,

digital and human assets to deliver those outcomes, and what doing so will look

and feel like.

All stakeholders involved in

developing and delivering the vision.

We believe in detailed and segmented understanding of our

citizen and business customers

These customers should be owned at the whole-of-government

level.

Decisions should be based upon the results of research and evidence

rather than assumptions being made about what customers think.

Real-time,

event-level understanding of citizen and business interactions with government

should be developed.

We believe in services built around customer needs, not

organizational structure

Customers should be provided with a “one-stop service”

experience in their dealings with government, built around their needs (such as

accessibility).

Government should not be continually restructured in order to

achieve this. Instead "customer franchises" should be created – small customer-focused teams that sit within

the existing structures of government and act as change agents for their

customer segments.

Services should be delivered across multiple channels using

Service-Oriented Architecture (SOA) principles to join it all up, reduce

infrastructure duplication, and encouraging customers into lower cost channels where

appropriate.

Organizational and business change must be addressed before money is

spent on technology.

A

cross-government strategy should be built for common citizen and business data

sets (e.g. name, address) and common customer applications (e.g.

authentication, payments, notifications).

We believe that transformation is done with citizens and

businesses, not to them

All stakeholders should be engaged directly in service design

and delivery.

Customers should be given the technology tools that enable them to create

public value themselves.

People

should be given ownership and control of their personal data - and all

non-personally identifiable data held by government should be freely open for

reuse and innovation by third parties.

We believe in growing the market for transformed services

Service transformation plans should be integrated with an effective

digital inclusion strategy to build access to and demand for e-services across

society.

We will use the benefits from future

universality of digital access to help fund the costs of ensuring digital

inclusion now.

Partnerships

should be built with other market players (in the private, voluntary and

community sectors) in recognition of their significant influence on customer

attitudes and behaviour and enable the market and others to work with

government to deliver jointly-owned objectives.

We believe in managing and

measuring key critical success factors:

Figure 2: The nine Critical

Success Factors

v v

v

Linkages

Delivering these

principles, in line with the [CSF1] Critical

Success Factors, requires government to re-visit – and potentially to

transform – every stage of the service delivery process. Developing, agreeing

and acting as guardians of the guiding principles is a core task for people

involved in [B2]

Program Leadership, and should be

addressed at an early stage in development of the [B1] Vision for Transformation and [B10] Roadmap for Transformation.

This section of the TGF

focuses on business management: that is, the key aspects of governance,

planning and decision making that need to be managed at a whole-of-government

level. This does not mean a top-down, centrally planned and managed

approach; it does mean taking a government-wide approach to:

•

establishing an integrated vision

and strategy;

•

underpinning this with

an operating model which balances the need for government-wide cohesion on the

one hand and local innovation on the other;

•

taking a “viral”

approach to implementation: establishing the business processes, capacity and

structures that can drive transformation and create sustained improvements over

time, even if all the steps of that transformational journey cannot be planned

in detail at the outset.

The core patterns within the

business management component of the TGF are:

·

[B1] Vision for Transformation

·

[B2] Program Leadership

·

[B3]

Transformational Operating Model

·

[B4] Franchise

Marketplace

·

[B5] Stakeholder

Collaboration

·

[B6] Policy Product Management

·

[B7] Supplier

Partnership

·

[B8] Skills

·

[B9] Common Terminology

and Reference Model

·

[B10] Roadmap for Transformation

Context

First among the [GP1] Guiding Principles is the need for [B2]

Program Leadership to

develop a clear, compelling and shared vision for the transformation program.

v v

v

The Problem

It is not the intent of the Transformational Government

Framework to describe some perfect “end-state” for government. All governments

are different: the historical, cultural, political,

economic, social and demographic context within which each government operates

is different, as is the legacy of business processes and technology

implementation from which it starts. So the Transformational Government

Framework is not a “one-size-fits-all” prescription for what a government

should look like in future.

Rather, each TGF program needs

to set its own clear vision. This will require agreement and clarity amongst

stakeholders on:

·

the social, economic and/or

environmental impacts that the TGF program seeks to achieve;

·

the challenges that a TGF program needs to overcome in order to deliver these

impacts and the vision should address – such as, for example:

−

Public sector budget pressures

−

Changing service needs

−

Infrastructure stress

−

Resource scarcity

−

Skills and market access

−

Growing population

−

Aging population

−

Mobile population

−

Economic inequality

−

Digital divide

·

how the future will “feel”

different for key stakeholders – so that the vision is articulated not in

technical terms, but also in human and emotional ones.

v v

v

The Solution

Program

Leadership must create a vision for

the TGF program that:

a)

is developed in an iterative and collaborative manner (that is, inclusive

of all stakeholder groups and informed by user research and engagement, with

social media and other technologies used to enable wide public participation in

the process);

b)

embraces the opportunities opened up by new technologies and delivery channels,

open data and effective collaboration;

c)

does so in a way which integrates these with the core socio-economic, political

and environmental vision for the future, rather than seeing them as somehow

separate from the government’s core strategic objectives;

d) can

be measured.

v v

v

Linkages

The vision should

be informed by the TGF program’s [GP1] Guiding Principles, and

developed through intensive [B5]

Stakeholder Collaboration. It is vital

to ensure that the vision can be expressed in terms of measurable outcomes and

that clear “line of sight” is established between all activities in the roadmap

and delivery of these outcomes for the program vision. Guidance on how to do

this effectively is set out at Benefit Realization.

Context

Development of a shared and

compelling [B1] Vision for Transformation requires significant

leadership and strategic clarity; delivery of the vision then requires that

leadership to be sustained over a period of years.

v v

v

The Problem

Transformational government cannot be pursued on a

project-by-project or agency-specific basis but requires a whole-of-government

view. At the same time, transformation cannot be delivered successfully through

traditional top-down program structures – so TGF programs need to find

effective ways to empower and enable leadership on a distributed, cross-government

basis.

There is no “ideal”

leadership structure for a transformation program. However, global experience suggests the

following factors are vital to address in whichever way is most appropriate for

the specific government context:

a)

A clear focus of accountability for the TGF program

as a whole.

At both the political and administrative

levels there should be an explicit functional responsibility for the TGF

program. These functions should be occupied by individuals with sufficient

authority to shape resource allocation and organizational priorities.

b)

Building a broad-based

leadership team across the government.

It is not essential that all Ministers and senior management are committed to the TGF program from the very outset.

Indeed, a key requirement of building and managing a [B10] Roadmap for

Transformation is to work in ways that nurture and grow support for

the strategy through the implementation process. However, it is important the TGF program is

not seen as a centralized or top-down. Sharing leadership roles for the design

and delivery of a program with senior colleagues across the government and with external partner organizations is therefore important.

c)

Bringing leaders together in

effective governance arrangements.

Government-wide governance systems need to be established at two levels:

·

the strategic governance level,

focused on defining required outcomes of the TGF program and ensuring effective

Benefit Realization;

·

the delivery governance level,

focused on implementation of the [B10] Roadmap for Transformation.

d)

Deployment of formal program

management disciplines.

To deliver effective government-wide transformation, it is vital to use a formalized program

management approach to develop and manage a portfolio of programs and projects

that together are intended to deliver the [B1] Vision for Transformation.

While these projects can be managed by many different stakeholders, they should

be brought together into an overall strategic program of work with:

·

an overall [BR1]

Business Case, supported by

measurement of clear success indicators;

·

prioritization of activities and

program changes, based on performance and feedback criteria linked to the programs

[GP1] Guiding Principles;

·

common frameworks for managing

strategic risks, issues and constraints, bought into by all delivery partners.

e)

Ensuring the right skills mix

in the leadership team.

Effective leadership of a transformation program requires the senior

accountable leaders to have access to a mix of key skills in the leadership

team which they build around them, including: strategy development skills,

stakeholder engagement skills, marketing skills, commercial skills and

technology management skills. Deployment of a formal competency framework, such

as Skills Framework for the Information Age [SFIA] can be helpful in

identifying and building the right skill sets.

f)

Allowing for organizations’

evolution over time.

Contributions by private and voluntary stakeholders are likely to be subject to

“engagement lifecycles”. Organizations are created, evolve and eventually merge

or decline. The continuity of assets and services needs to be actively managed

throughout this evolutionary process.

g)

Ensuring an open and

transparent governance process

Finally, transparency is important in order to build trust, strengthen

accountability for delivery of the TGF program, and to facilitate openness and

collaboration with all stakeholders. This means that the leadership of a TGF

program should aim to publish all key vision and strategy documents, make names

and contact details of program leaders publically available, and publish

regular updates of performance and delivery against the [B10] Roadmap for

Transformation.

v v

v

The Solution

A TGF program should

therefore establish leadership and governance

arrangements that ensure:

a)

a clear focus of accountability

within the government for the program;

b)

a broad-based leadership team

across the government;

c)

government leaders are brought

together into effective governance arrangements, at both the strategic

and delivery levels;

d) deployment of formal program

management disciplines and prioritization of activities and

program changes, based on performance and feedback criteria;

e)

the right skills mix in the

leadership team;

f)

an ability to manage

organizational evolution among partner organizations, and to deliver

continuity through political changes;

g)

openness and transparency in the governance process, including through digitally-enabled models of wider

civil participation.

v v

v

Linkages

Key tasks for the leadership

of a TGF program include:

•

articulating and acting as

guardians of the [GP1] Guiding Principles for the TGF

program;

•

ensuring that the program is

aligned to deliver a clear, compelling and agreed [B1] Vision for Transformation;

•

acting as champions and

ambassadors for the TGF approach as part of [B5]

Stakeholder Collaboration;

•

developing and overseeing a [B10] Roadmap

for Transformation;

•

ensuring line-of-sight

from all within that roadmap and the strategic outcomes being targeted by the program

through its Benefit Realization framework;

•

ensuring that the

program is effectively managing all of the [CSF1]

Critical Success Factors.

[B3] Transformational Operating

Model

Context

A central task of the [B2] Program Leadership and [B5]

Stakeholder Collaboration is to enable the machinery of government to

deliver customer-centric services “one stop services”. They need to cooperate

with stakeholders in developing a new operating model that delivers those

services in practice, when and where they are needed.

v v

v

The Problem

The failure to create an appropriate new operating model

has arguably been the greatest weakness of most traditional e‑Government

programs. The transition to e‑Government has involved overlaying

technology onto the existing operating model of government: an operating model

based around existing functionally-oriented government departments and

agencies. These behave like unconnected silos in which policy-making, budgets,

accountability, decision-making and service delivery are all embedded within a

vertically-integrated delivery chain based around delivery functions

rather than recipient needs.

The experience of governments around the world over the last

two decades has been that silo-based delivery of services simply does not

provide an effective and efficient approach to e-government. Many attempts have

been made by governments to introduce greater cross-government coordination,

but largely these have been "bolted on" to the underlying business

model, and hence experience only limited success. Without examination of, or

fundamental change to, the underlying business model level, the design and

delivery of services remains fragmented and driven by the structures of

government, rather than the needs of the government’s customers.

Figure 3 below illustrates

the traditional operating model which is still typical of most governments:

·

the individual citizen or business has to engage separately with

each silo: making connections for themselves, rather than receiving seamless

and connected service that meets their needs;

·

data and information has typically been

locked within these silos, limiting the potential for collaboration and

innovation across the government, and limiting the potential to drive change at

speed.

Figure 3 –

Traditional operating model: where governments have come from

Government transformation programs involve a shift in

emphasis, away from silo-based delivery and towards an integrated,

multi-channel, service delivery approach: an approach which enables a

whole-of-government view of the customer and an ability to deliver services to

citizens and businesses where and when they need it most, including through

one-stop services and through private and voluntary sector intermediaries.

Key features of this shift to

a transformational operating model include:

a)

investing in smart data, i.e. ensuring that data on the performance and use

of the government’s physical, spatial and digital assets is available in real

time and on an open and interoperable basis, in order to enable real-time

integration and optimization of resources;

b)

managing public sector data as

an asset in its own right, both

within the government and in collaboration with other significant data owners

engaged in the TGF program;

c)

enabling

externally-driven, stakeholder-led innovation by citizens, communities and the private and voluntary

sectors, by opening up government data

and services for the common good:

·

both at a technical level, through

development of open data platforms;

·

and at a business level, through

steps to enable a thriving market in reuse of public data together with release

of data from commercial entities in a commercially appropriate way;

d)

enabling internally-driven,

government-led innovation

to deliver more sustainable and

citizen-centric services, by:

·

providing citizens and businesses

with public services, which are accessible in one stop, over multiple channels,

that engage citizens, businesses and communities directly in the creation of

services, and that are built around user needs not the government’s

organizational structures;

·

establishing an integrated

business and information architecture which enables a whole-of-government view

of specific customer groups for government services (e.g. elderly people,

drivers, parents, disabled people);

e)

setting holistic

and flexible budgets,

with a focus on value for money beyond standard departmental boundaries;

f)

establishing

government-wide governance and stakeholder management processes to support and evaluate these changes.

Figure 4 summarizes these

changes to the traditional way of operating which transformational government

programs are seeking to implement.

Figure

4 – New integrated operating

model: where governments are moving to

v v

v

The Solution

TGF programs should therefore ensure

that their [B1] Vision for Transformation includes the need to establish

a Transformational Operating Model to help build services around citizen and

business needs, not just government’s organizational structure. This will

include:

- providing citizens and businesses with services which

are accessible in one stop and ideally offered over multiple channels;

- enabling those services also to be delivered by private

and voluntary sector intermediaries.

The Transformational Operating Model must go beyond

simple coordination between the existing silos and should include:

- An integrated

business and information architecture which enables a whole-of-government

view of the customer, thus making possible both the integration of

services and simple, effective cross-agency customer journeys;

- Incentives and business processes that encourage the

internal cultural change and cross-silo collaboration needed to drive the

integration and joining-up of services;

- A cross-government strategy for shared development,

management and re-use of common customer data sets, applications, and

applications interfaces (e.g. authentication, payments, and notifications);

- Opening up public data for re-use and innovation by the

private and voluntary sectors, and directly by citizens and businesses.

v v

v

Linkages

Rather than attempting to restructure Government to deliver

such a Transformational Business Model, the [B4] Franchise Marketplace SHOULD

be considered as the recommended approach to implement this model.

Multi-channel delivery of services can be provided through optimized [S6] Channel Transformation and

public data can be opened up to create new sorts of value through [S1] Stakeholder Empowerment.

Common customer data sets can be built as shared services with customer data

under customer control and managed using [T2] Technology Development and

Management. This pattern is facilitated by placing citizen, business,

and organizational data under their control as set out in [S3] Identity and Privacy Management.

[B4]

Franchise Marketplace

Context

The [B3] Transformational Operating Model underpins

the requirement of Transformational Government programs to build services

around citizen and business needs rather than government’s organizational

structure. This includes having a whole-of-government view of the customer; as

well as providing those customers with services that are accessible when and

where they are most needed and ideally offered over multiple channels. This can

be achieved using a “Franchise Marketplace”

v v v

The

Problem

There is a seeming paradox -

given the huge range of government service delivery - between keeping “global”

oversight of all aspects of a customer’s needs at the same time as delivering

well-targeted services in an agile way.

Too many government departments and agencies have

overlapping but partial information about their citizens and business

customers, but nobody takes a lead responsibility for owning and managing that

information across government, let alone using it to design better services.

One way of addressing this problem has been to

restructure government: to put responsibility for customer insight and service

delivery into a single, central organization which then acts as the “retail

arm” for government as a whole to interact with all its customers.

Under this model, one organization becomes

responsible for the service delivery function across all channels -

face-to-face, contact centre, web - with relevant staff and budgets being

transferred from other agencies.

This is one way of implementing the [B3]

Transformational Operating Model as required but with one obvious

difficulty: making structural changes to government can be extremely hard. The

sheer scale of the “government business” means that any changes need to be

implemented carefully over a long period of time and take account of the

inherent risks in organizational restructuring. The resulting large-scale

delivery organization needs extremely careful management if it is to maintain the

agility that smaller-scale, more focused delivery organizations can achieve.

An alternative

approach is called the “Franchise Marketplace”: a model that permits the

joining-up of services from all parts of government and external stakeholders

in a way that makes sense to citizens and businesses, yet without attempting to

restructure the participating parts of government. Conceptually,

this leads to a model where the existing structure of government continues to

act as a supplier of services, but intermediated by a "virtual"

business infrastructure based around customer needs. A top-level view of such a

virtual, market-based approach to transformational government is set out in the

figure below:

Figure 5:

Overview

of the Franchise Marketplace

Key features of this business model

are:

The

model puts into place a number of agile cross-government virtual

"franchise businesses" based around customer segments (such as, for

example, parents, motorists, disabled people). These franchises are responsible

for gaining full understanding of their customers' needs so that they can

deliver quickly and adapt to changing requirements over time in order to

deliver more customer centric services - which in turn, is proven to drive

higher service take-up and greater customer satisfaction.

Franchises

provide a pragmatic and low-risk operational structure that enables

functionally-organized government agencies at national, regional and local to

work together in a customer-focused "Delivery Community". They do

this by:

-

Enabling government to create a "virtual" delivery

structure focused on customer needs;

-

Operating across the existing structure of Government (because

they are led by one of the existing "silos") and resourced by

organizations that have close links with the relevant customer segment

including, possibly, some outside of government;

-

Dividing the task into manageable chunks;

-

Removing a single point of failure;

-

Working to a new and precisely-defined operating model so as to

ensure consistency;

-

Working across and beyond government to manage the key risks to

customer-centric service delivery;

-

Acting as change agents inside‑Government departments /

agencies.

The

model enables a "mixed economy" of service provision:

firstly,

by providing a clear market framework within which private and voluntary sector

service providers can repackage public sector content and services; and

secondly by

deploying ‘Web 2.0’ type approaches across government that promote re-use and

‘mash-ups’ of existing content and services, to make this simpler and cheaper

at a technical level.

The whole model is

capable of being delivered using Cloud Computing.

This Franchise model represents an important break-through

in the shift from a traditional e‑Government approach towards

transformational government. Certainly, the model as a whole or key elements of

it has been adopted successfully in governments as diverse as the UK, Hong

Kong, Croatia, Abu Dhabi and Australia (where it has been adopted by both the

South Australia and Queensland governments).

It is clearly possible that alternate models may develop in

future. But however the Transformational Government agenda develops, every

government will need to find some sort of new business model along these lines,

rather than continue simply to overlay technology onto an old silo-based

business model built for an un-networked world.

v v v

The Solution

Establish a number of agile, cross-government, virtual

"franchise businesses" that:

a) are

based around customer segments (such as, for example, parents, motorists, disabled

people) and that sit inside the existing structure of government;

b) deliver

customer-centric, trusted and interoperable content and transactions to

citizens, businesses and other organizations; and

c) act

as champions of and drivers for customer-centric public service improvement.

v v v

Linkages

The Franchise Marketplace is a specific example of a [B3] Transformational Operating

Model and is considered as the most effective and lowest risk way of

delivering the element of the [GP1]

Guiding Principles which requires Transformation Programs to “Build

services around customer needs, not organizational structure”. Further details

on the key stakeholders who need to be involved in enabling the Franchise

Marketplace model are contained at Appendix B.

[B5] Stakeholder Collaboration

[B5] Stakeholder Collaboration

Context

Effective stakeholder

collaboration is critical. Establishing a process of sustainable change

requires a critical mass of actors inside and outside of the government to be

both engaged and supportive. Delivering a [B1] Vision for Transformation cannot

be done without meaningful stakeholder collaboration.

The private, voluntary and

community sectors have considerable influence on citizen attitudes and

behavior. These influences must be transformed into partnerships which enable

the market to deliver program objectives. This requires a “map” of all

stakeholders as part of overall business management.

v v

v

The Problem

It is not enough to map and understand stakeholder

relationships and concerns. Classic models of

stakeholder engagement also need to be re-assessed.

Leaders from all parts of the government organization, as

well as other organizations involved in the program, need to be motivated for

the program to succeed and need to be engaged in clear and collaborative

governance mechanisms to manage any risks and issues. The development and

delivery of an effective Transformational Government program requires

engagement with a very wide range of stakeholders, not only across the whole of

government but also, in most cases, with one or more of the private, voluntary

and community sectors as well as with public service customers. A significant

effort is needed to include all stakeholders in the governance of the

Transformational Government program at an appropriate and effective level.

Key elements are set out below that a conformant TGF program

will need to address in developing its Collaborative Stakeholder Governance

Model, if it is to engage successfully with stakeholders and align them

effectively behind shared objectives.

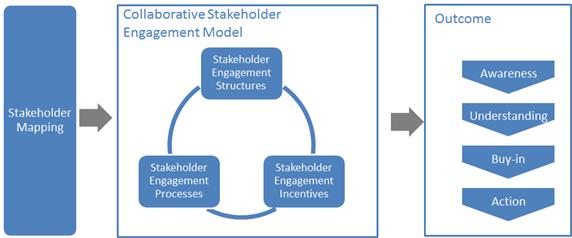

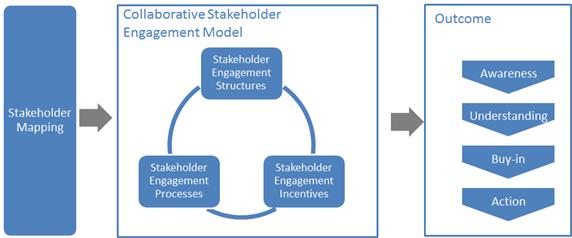

Figure 6: Overview of Collaborative Stakeholder

Governance

It is vital to describe and map the complete landscape of

relevant stakeholders. The Transformational Government Framework puts the

individual – whether acting on their own behalf as a citizen or on behalf of

another citizen or of a business– at the centre:

Figure 7:

Landscape

of some key stakeholders

This view deliberately and completely avoids

the rather generic concept of ‘User’ that is dominant in traditional IT

stakeholder engagement models, preferring rather to identify the different

interests and concerns that are at stake (the mauve labels) and the key groups

of stakeholders (the different people icons) in the development of any service.

The figure

is by no means complete nor the only ‘valid’ view. It seeks instead to

illustrate that the process of transformation requires reappraisal of the

current set-up and assessment of what needs to change.

By clearly separating out key stakeholder

groups and starting to understand and articulate their specific concerns as

stakeholders (any individual’s role may vary according to context:

in one situation, a person is a parent; in another, a policy-maker; or another,

a service provider), we can start to understand how stakeholders relate (in

different roles): to each other; to various administrations and services

involved; to policy drivers and constraints; and how these all come together in

a coherent ecosystem supported by a Transformational Government Framework. In

this view:

A service

(or ICT capability made available as a service) is understood as responding to

a set of requirements and policy goals (some of which overlap) – stakeholders

concerned at this level include, for example, case workers in a public

administration or developers who have worked with them in delivering a specific

service;

Requirements encapsulate and formalize vaguely stated

goals and needs of citizens and businesses and take on board the policy goals

of the political sponsor or champion – stakeholders at this level include, for

example, managers of public service who can articulate the needs of their

respective services, the information and systems architects who capture those

needs as formal requirements that engineers can work with to develop services;

Policy

Goals capture the high-level concerns and priorities of the political

authorities and continually assess how these goals reflect key citizen and

business concerns – stakeholders include policy makers and senior management as

well as consultants and analysts involved in helping identify technology and

administrative trends that can be used to leverage those goals; and finally;

Citizen and Business Needs that, ultimately, can only

be fully understood by the people concerned themselves – nonetheless

stakeholders at this level can also include citizen or business associations,

consumer and other interest groups who engage with policy makers to advance the

interests of certain groups with distinct needs and are able to articulate

those needs in ways that can be used by analysts and consultants.

The various ellipses in the diagram above are deliberately

not concentric circles. This is to underline that the process of establishing a

service or capability is not a linear one going from needs, goals and

requirements. In reality stages are often inter-related.

The mapping of stakeholders and their principal concerns at

a generic level is used as a key input to the TGF [B9] Reference Model

and that needs to be validated within any TGF program. It is valuable as a tool

for encouraging collaborative governance as it renders explicit many of the

relationships and concerns that are often left implicit but nonetheless impact

on an organization’s ability to reflect stakeholders’ concerns.

However, it is not

enough simply to map and understand stakeholder relationships and concerns. An

effective TGF program will also address the three other dimensions of the model

illustrated above:

Stakeholder Engagement Structures: the organizational arrangements put in place to lead

the transformation program, e.g.:

-

central unit(s)

-

governance boards

-

industry partnership board.

Stakeholder Engagement Processes: the processes and work flows

through which the TGF Leadership and the different TGF Stakeholders interact, e.g.:

-

reporting and accountability processes

-

risk management processes

-

issue escalation processes

-

consultation processes

-

collaborative product development processes.

Stakeholder Incentives: the set of levers available to drive

change through these governance structures and processes. These will vary by

government, but typical levers being deployed include:

-

central mandates

-

political leadership

-

administrative championship

-

personal performance incentives for

government officials

-

alignment between public policy objectives

and the commercial objectives of private sector partners.

There is no one right model for doing this successfully, but

any conformant TGF program needs to make sure that it has used the framework

above to define its own Collaborative Stakeholder Engagement Model which

explicitly articulates all of these elements: a comprehensive stakeholder map,

coupled with the structures, processes and incentives needed to deliver full understanding

and buy-in to the program, plus effective stakeholder action in support of it.

Collaboration between TGF Programs

The model clearly focuses attention within any

specific TGF program. However (and increasingly) collaboration is required also

between governments and, by implication, between TGF programs. In the

figure below, we see that collaboration between TGF programs is favoured at the

political, legal and organizational levels and only later, if and when

necessary, at the more ‘tightly-coupled’ semantic and technical levels.

Figure 8: Collaboration between TGF programs

through different levels of Interoperability

This approach is also consistent with the SOA paradigm for

service development – not only are requirements defined and services offered

independently of any underlying technology or infrastructure but also one TGF

program can be seen (and may need to be seen) as a ‘service provider’ to

another TGF program’s ‘service request’. For example, a business wishing to

establish itself in a second country may need to provide authenticated

information and credentials managed by government or business in the first

country.

A further advantage of this approach is that it becomes

easier to identify and manage high level government requirements for services:

whether in the choice of ICT standards that may need to be used to address a

particular technology issue or determining the criteria for awarding public

procurement contracts, this approach allows a ‘loose-coupling’ at the level of

clearly defined high-level policy needs rather than the more tightly-coupled

and often brittle approach of specifying particular technologies, software or

systems.

v v

v

The Solution

TGF programs should

establish, and give high priority and adequate resources to, a formal managed stakeholder engagement program.

This should be led by a senior executive and integrated into the roles of all

involved in delivering the TGF program, and should cover:

·

Stakeholder

modelling: identifying and mapping the relationships

between all key stakeholders in the program (users, suppliers,

delivery partners elsewhere in the public, private and voluntary sector,

politicians, the media, etc.); maintaining and updating the stakeholder model

on a regular basis;

·

A

collaborative stakeholder governance model: establishing

a clear set of structures, processes and incentives through which the [B2]

Program

Leadership

and

the different stakeholders will interact, and covering:

‒ stakeholder

participation: ensuring that all stakeholders have a

clear understanding of the TGF program and how they will benefit from it, and

have effective and inclusive routes (including through use of digital media) to

engage with and participate in the program;

‒ cross-sectoral

partnership: engaging effectively with stakeholders

from the private, public and voluntary sectors to deliver the program in a way

that benefits all sectors;

‒ engagement

with other transformation programs to

learn lessons and exchange experience.

v v

v

Linkages

Stakeholder Collaboration should be established as a formal

workstream within the [B10] Roadmap for

Transformation, with measurable performance metrics built into the Benefits Realization framework. Stakeholder

engagement underpins all other parts of the TGF, because anyone in involved in

the realization of the [B1] Vision for

Transformation (or receiving benefits as a result) is considered

a stakeholder. However, intensive multi-stakeholder engagement is particularly

important for [B1] Vision

for Transformation, [B2]

Program Leadership,

[B7] Supplier

Partnership,

[S2] Brand-led Service

Delivery, [S1] Stakeholder Empowerment and [S3] Identity

and Privacy Management. The development of successful

customer franchises within the [B4] Franchise Marketplace

will depend on the effectiveness of collaborative governance – while at the

same time helping improve stakeholder collaboration significantly.

[B6] Policy Product Management

Context

In any government, “Policy

Products” - the written policies, frameworks and standards which inform

government activity - are important drivers of change. In the context of

Transformational Government, the [B2] Program Leadership will use

a wide set of Policy Products to help deliver the program – and, in particular,

to ensure interoperability between the different organizations and systems

involved in the TGF program.

v v

v

The Problem

Traditional policy approaches for e-government have often

been too narrowly focused. An effective Transformational Government program

requires a more holistic approach to policy development.

We define a "Policy Product" as: any document that

has been formally adopted on a government-wide basis in order to help achieve

the goals of transformational government. These documents vary in nature (from

statutory documents with legal force, through mandated policies, to informal

guidance and best practice) and in length (some may be very lengthy documents;

others just a few paragraphs of text). Policy Products are important drivers of

change within government: first because the process of producing them, if managed

effectively, can help ensure strategic clarity and stakeholder buy-in; and

second because they then become vital communication and management tools. Conversely, if policy products are poorly managed and/or

out of date, then they can become significant constraints to effective change.

Over recent years, several governments have published a wide

range of Policy Products as part of their work on e-Government, including

e-Government Visions, e-Government Strategies, e-Government Interoperability

Frameworks, and Enterprise Architectures. Other governments are therefore able

to draw on these as reference models when developing their own Policy

Products. However, we believe that the set of Policy Products required to

ensure that a holistic, government -wide vision for transformation can be

delivered is much broader than is currently being addressed in most

Interoperability Frameworks and Enterprise Architectures.

The European Commission

identifies five broad interoperability domains via the European Interoperability

Framework (EIF): technical, semantic, organizational, legal, and policy

interoperability. While this framework is conceptually complete, TGF programs

will find it helpful to map the five EIF dimensions against the three

government-wide delivery and governance processes identified in the TGF:

business management, service management, and technology and data asset

management.

The resulting matrix represents the landscape within which a

government needs to map the barriers to interoperability which it faces, and

relevant constraints placed by national or international policy commitments. In

each cell of the matrix, some action is likely to be needed.

This Policy Product Matrix MUST be used to create a map of

all the Policy Products needed to deliver a particular TGF program effectively.

This matrix maps the three delivery processes of the TGF (Business Management, Service

Management and Technology and Digital Asset Management) against the five interoperability

domains identified in the [EIF].

v v

v

The Solution

TGF Programs should therefore

use the Policy Product Matrix below as a tool to:

a)

help identify key barriers to

interoperability in their TGF program;

b)

identify, for each and every cell in the matrix, the policy product(s)

that are needed to deliver the Transformational Program effectively. Nil, one,

or multiple policy product(s) may be required per cell. Consideration MUST be

given to every cell as to which policy products might be included.

c)

establish policies and actions to address these,

drawing on international, European or national standards where possible; and

d) promote

commonality of approaches and easier linkages with other TGF programs.

Delivery Processes

|

Interoperability Levels

|

|

Political

|

Legal

|

Organizational

|

Semantic

|

Technical

|

|

Business Management

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Service Management

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Technology and Digital Asset Management

|

|

|

|

|

|

v v

v

Linkages

The [B2] Program

Leadership should undertake this policy gap analysis through [B5] Stakeholder

Collaboration, and then ensure that the accountability and process for

developing any missing Policy Products is embedded within the [B10] Roadmap for Transformation.

A full analysis of

the Policy Products which we recommend are typically needed to deliver an

effective and holistic transformation program are described in a separate TGF Committee

Note “Tools and Models for the Business Management Framework”. Although the

detailed Policy Products in that note are advisory and not all of them may be

needed, any conformant transformation program MUST use the overall framework

and matrix of the Policy Product Map in order to conduct at minimum a gap

analysis aimed at identifying the key Policy Products needed for that

government, taking the Committee Note into account as guidance.

[B7] Supplier Partnership

[B7] Supplier Partnership

Context

Governments rely heavily on

suppliers to deliver large parts of their services. These suppliers are usually

external organizations but they can also be other internal parts of government.

The management of supplier relationships needs to sit above the management of

individual contracts and it is important that distinction is fully understood

by all parties. Legacy supplier relationships and procurement policies have often

raised significant barriers to transformation programs.

v v

v

The Problem

Transformational

Government programs require effective, partnership-based relationships with

suppliers but the relationships themselves can obscure or prevent the vision of

more citizen-centric and integrated service delivery.

Supplier partnerships should set

out a formalized and robust way of managing, monitoring and developing supplier

and commissioning party performance whilst at the same time minimizing risks to

the business. ‘Partnerships’ focus on the overall relationship over time rather

than the specific relationship around an individual, time-limited, contract.

Yet traditional public sector

procurement and supplier management practices can represent a significant

obstacle to transformational government. From both the public and private

sector sides of the market, there is strong evidence that such practices can

stifle innovation and inhibit the ability of governments and industry jointly

to undertake real life R&D and to pool intellectual property for mutual

benefit.

Equally, there is increasing

consensus on new, “smarter” approaches to supplier partnership, which are

already starting to develop and should be more widely adopted. Figure 9

summarizes some of the key elements of this shift.

|

|

|

Traditional public procurement and supplier

management

|

|

Transformational Supplier Partnership

|

|

Silo-based procurement, with

requirements set by individual agencies within the government…

|

|

An integrated strategic

approach to the commissioning of services, across the government and in

partnership with other public service delivery organizations

|

|

…and with little ability to

fund solutions that benefit multiple organizations

|

|

Budget alignment mechanisms

enable effective provision of common good platforms and services

|

|

The government defines the

technology and other inputs it wants to buy, and the immediate outputs it

wants these to deliver

|

|

The government defines the

outcomes and service levels it wants to achieve

|

|

Requirements are developed

internally by the government

|

|

Requirements are developed

iteratively, in partnership between customer, commissioner and supplier

|

|

The government brings its

requirements to the market in a piecemeal manner

|

|

Published pipelines of future

requirements help to stimulate the market and enable suppliers to propose new

cross-cutting solutions to deliver multiple requirements

|

|

Government agencies define

their requirements in isolation from each other

|

|

Joint procurement initiatives,

facilitated by shared pipelines, enable shared services across more than one

agency and also stimulate the market for standardized and replicable public

sector solutions (including via Cloud Computing)

|

|

Procurement and contracting is

based around purchaser–provider, client–agent relationships

|

|

A range of more innovative

delivery models are deployed, including joint ventures and partnerships

between government, industry and academia that promote collaborative

solutions while safeguarding the intellectual property of each

|

|

Procurement decisions focus

primarily on price

|

|

Procurement decisions focus

primarily on long-term value for money, including:

·

total

cost of ownership (including costs of exit);

·

the

suppliers’

ability to innovate;

·

confidence

in delivering the expected business benefits.

|

|

IT as a capital investment

|

|

IT as a service

|

|

Long-term, inflexible

contracts

|

|

Appropriate use of short-term,

on-demand purchasing

|

|

Bespoke, vertically-integrated

solutions for each line of business

|

|

Sharing and re-using

standardized components, drawing on best-of-breed building blocks and

commercial-off-the-shelf products

|

|

Government systems are unable

to interoperate, due to over-reliance on proprietary systems

|

|

Interoperability based on open

standards is designed into all procurements from the outset

|

|

Important public data-sets

cannot be opened up because they are owned by suppliers

|

|

Standard contractual

arrangements ensure that all government suppliers make public data available

via open standards and either for free or, where appropriate, on fair,

reasonable and non-discriminatory terms

|

|

No incentives on suppliers to

share, collaborate and innovate with other stakeholders

|

|

Contractual arrangements

encourage collaboration with others to create new value, and the sharing of

common assets, with benefits being shared between the government and its

suppliers

|

|

The government buys from a

limited pool of large suppliers

|

|

The government buys from a

large pool of small suppliers, plus strategic relations with a smaller number

of platform suppliers who themselves integrate with many SMEs

|

|

Government

leaders focus on managing relationships with a few large vendors

|

|

Government leaders focus on

nurturing and managing an innovation ecosystem

|

Figure 9 – Towards

transformational supplier

partnerships

v v

v

The Solution

TGF programs should

therefore:

a)

take an integrated view of the

program’s procurement requirements, establishing

governance arrangements that enable a government-wide overview of major

procurements;

b)

review procurement policies to

ensure they align with smart contracting principles:

·

focus on procuring business

outcomes: specify what the

supplier should achieve, not how it should achieve it (in general, this

includes procuring services not assets);

·

build open data into all

procurements: be clear that all

data is to be owned by the government not the supplier, or establish clear

requirements for the supplier to make data available via open standards and

fair, reasonable and non-discriminatory terms;

·

incentivize innovation and

collaboration: ensure that

contractual arrangements encourage collaboration with others to create new

value, and the sharing of common government assets;

·

avoid supplier lock-in, by integrating interoperability requirements into

all ICT procurement, using commercial-off-the-shelf products and open standards

wherever possible, and factoring in the costs of exit from the outset;

c)

work to nurture an innovation ecosystem across the government

and its suppliers, including by:

·

publishing the government’s

procurement policies, ensuring

that all changes following the review are widely known;

·

publishing and updating a

pipeline of major procurement

opportunities;

·

early and iterative

engagement with potential

suppliers, including local and other SMEs, to benefit from innovation

and stimulate the market;

·

stimulating SME-led

innovation, including through use

of competitions and placing SME-engagement requirements on large suppliers;

·

driving forward the internal cultural and behavioural

changes entailed by the above recommendations.

v v

v

Linkages

Successful supplier

partnerships require specific skills sets to effectively manage the

relationship. Attention should be given to this as part of the wider focus on

ensuring the requisite [B8] Skills

are available to the program. The need

to nurture an innovation ecosystem of suppliers should be a major theme of [B5]

Stakeholder Collaboration, and

will be facilitated by adoption of the [B4]

Franchise Marketplace. In

reviewing procurement and contracting policies, program leaders should seek to

align contracting principles with the strategy for open,

service-oriented, IT architecture set out in [T2]

Technology Development

and Management.

[B8] Skills

Context

Implementing

a Transformational Government program and establishing [S2] Brand-Led Service Delivery involves taking a holistic,

market-driven approach to service design and delivery, which in turn often

requires new skills. Part of the responsibility of [B2] Program

Leadership is to ensure that program leaders have the skills needed to

drive all aspects of the program. This focus on skills has of course to be part

of an effective HR Management discipline.

v v

v

The Problem

Governments generally lack the key skills to manage

service development. Where they do exist there is often reliability on a small

number of individuals with no continuity plans in place for when those

individuals are either absent for any reason or leave the team.

The full range of business change, product and marketing

management, program management, and technology skills needed to deliver transformational

change does not already exist in the organization.

Many of the policy products required for the

Transformational Government program will take governments into new territory

and it is unlikely that they will have all the skills necessary to develop

these in-house.

v v

v

The Solution

Ensure the right skills mix is available to the program,

particularly in the leadership team but also throughout the whole

delivery team.

Map out the required skills together with a clear

strategy for acquiring them and a continuity plan for maintaining them.

Be prepared to buy-in or borrow the necessary skills in

the short term to fill any gaps.

Ensure that the program leaders, i.e. the

senior accountable leaders, have the skills needed to drive ICT-enabled

business transformation, and have access to external support.

Ensure there is skills integration and skills transfer by

having effective mechanisms to maximize value from the skills available in all

parts of the delivery team, bringing together internal and external

skills into an integrated team.

v v

v

Linkages

The development of a Transformation Competency Framework is

a good way of producing a taxonomy of the competencies required to deliver

ICT-enabled transformation, which should then be underpinned by tools enabling

organizations to assess their competency gaps and individuals to build their

own personal development plans. Deployment of a formal competency framework

such as [SFIA] can be helpful in identifying and building the right

skill sets. As an example see the UK’s Competency and Skills Framework which is

available at http://www.civilservice.gov.uk/networks/government-it-profession/framework.

See also [B6] Policy

Product Management, [B7]

Supplier Partnership and [CSF1]

Critical Success Factors.

[B9] Common Terminology and Reference Model

Context

In any change program of the breadth and complexity that the

TGF supports, it is vital that all stakeholders have a common understanding of

the key concepts involved and how they interrelate, and have a common language

to describe these in.

v v

v

The Problem

Leadership and communication both break down when

stakeholders understand and use terms and concepts in very different ways,

leading to ambiguity, misunderstanding and, potentially, loss of stakeholder

engagement.

In everyday life, we use terms – ‘citizen’, ‘need’,

‘service’ – as common, often implicitly accepted labels for concepts.

The concept is the abstract mental idea (which should be universal and language

independent) to which the term gives a material expression in a specific

language. Particularly in an international environment such as global

standardization initiatives, the distinction is important as it is common

concepts that we wish to work with, not common terms.

This distinction also helps avoid common modeling pitfalls.

Terms that may seem similar or the same across two or more languages may

actually refer to different concepts; or a single term in one language could be

understood to refer to more than one concept which another language expresses

with discrete terms: For example, the English term ‘service’ can refer

to different concepts - an organizational unit (such as ‘Passport

Service’ or ‘Emergency Services’) or something that is performed by one for

another (such as ‘a dry cleaning service’ or ‘authentication service’), whereas

discrete terms are used for the discrete concepts in German (‘Dienst’ or

‘Dienstleistung’ respectively for the two examples above). As the TGF is

intended for use anywhere in the world, it is important to ensure that

(ideally) global concepts can be transposed and translated and thus understood

in other languages: we therefore need to associate an explicit definition with

each concept as we do in a dictionary. The TGF uses a standard structure and

methodology to create its terminology

and we recommend that such an approach should be maintained in any extension of

the terminology.

Concepts do not exist in isolation. In addition to clear

definitions and agreed terms, It is the broader understanding of the

relationships between concepts that give them fuller meaning and allow us to

model our world, our business activities, our stakeholders, etc. in a way that

increases the chance that our digital systems are an accurate reflection of our

work. Any conformant agency should be able to use a common terminology without

ambiguity and be sure that these terms are used consistently throughout all

work.

The Solution

Ensure that all stakeholders have a clear, consistent and

common understanding of the key concepts involved in Transformational Government;

how these concepts relate to each other; how they can be formally modeled; and

how such models can be leveraged and integrated into new and existing