In the increasingly common situation of

governments being expected to deliver better and more services for less cost

whilst maintaining high-level oversight and governance, the Transformational

Government Framework provides a framework for designing and delivering an

effective program of technology-enabled change at all levels of government.

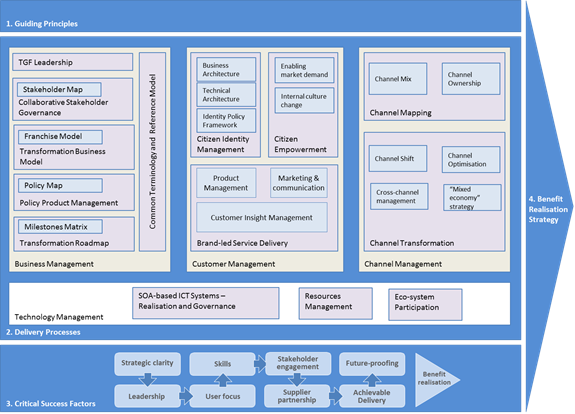

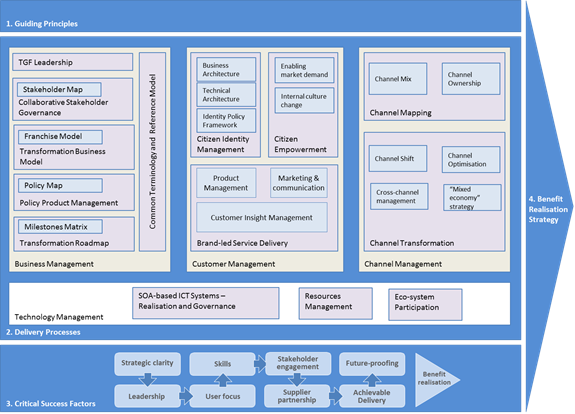

The Transformational Government Framework

can be seen schematically below, made up of four high-level components:

Figure 1: The overall framework

Each of these components is described in more

detail below.

Component 1:

Guiding Principles

The TGF Guiding Principles are set out

below, and must be used by any Transformational Government program conforming

to the TGF.

·

Own the customer at the whole-of-government

level

·

Don't assume you know what users of your

services think - research, research, research

·

Invest in developing a real-time, event-level

understanding of citizen and business interactions with government

·

Provide people with one place to access

government, built around their needs (such as accessibility)

·

Don't try to restructure‑Government to do

this - build "customer franchises" which sit within the existing

structure of government and act as change agents

·

Deliver services across multiple channels - but

use Service-Oriented Architecture (SOA) principles to join it all up, reduce

infrastructure duplication, and to encourage customers into lower cost channels where possible

·

Don't spend money on technology before

addressing organisational and business change

·

Don't reinvent wheels - build a

cross-government strategy for common citizen data sets (e.g. name, address) and

common citizen applications (e.g. authentication, payments, notifications)

·

Engage citizens directly in service design and

delivery

·

Give citizens the technology tools that enable

them to create public value themselves

·

Give citizens ownership and control of their

personal data - and make all non-personal government data freely open for reuse

and innovation by citizens and third parties

·

Ensure that your service transformation plans

are integrated with an effective digital inclusion strategy to build access to

and demand for e-services across society

·

Recognise that other market players (in the

private, voluntary and community sectors) will have a significant influence on

citizen attitudes and behaviour - so build partnerships which enable the market

and others to work with you to deliver jointly-owned objectives.

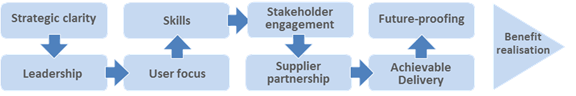

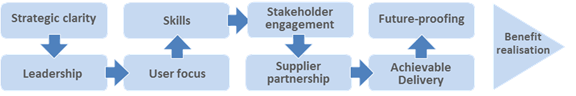

Figure 2: The nine Critical Success Factors

These nine factors are covered in Component

2 of the TGF.

Component 2: Critical Success Factors

Conformant

Transformational Government programs manage and measure these Critical Success

Factors throughout the life of the program.

·

All-of-Government view: Transformational government cannot be pursued on a

project-by-project or agency-specific basis but requires a whole-of-government

view, connecting up relevant activities in different agencies at different

levels of government within and between countries.

·

Clear vision:

all program stakeholders have a common, agreed and comprehensive view of what

the program is seeking to achieve. In particular, we do not spend money on

technology before identifying the key organizational and business changes

needed to deliver our vision.

·

Strong business case: we know what outcomes we want to achieve, have base-lined where we

are now, and know how we will measure success.

·

Focus on results: although we have a vision of where we want to go, and a set of

principles by which we will move forwards, we do not over-plan. Instead, our

strategy focuses on taking concrete, practical steps in the short to medium

term, rather than continually describing the long-term vision.

·

Sustained support: political leaders and senior management are committed to the

program for the long term. This is particularly relevant given the realities of

changing political leadership and underlines the need for continuity across

those changes.

·

Leadership skills: our program leaders have the skills needed to drive ICT-enabled business

transformation, and have access to external support

·

Collaborative governance: leaders from all parts of our and other organizations involved in

the program are motivated for it to succeed, and are engaged in clear and

collaborative governance mechanisms to manage any risks and issues.

·

A holistic view of the customer: we understand who the customers for our services are - not just

for individual services - but across the Government as a whole. We know our

customers, both internal and external, are different - and understand their

needs on a segmented basis.

·

Citizen-centric delivery: citizens can access all our services through a

"one-stop" service. This is available over multiple channels and that

respond to different needs, but we use web-based services to join it all up and

reduce infrastructure duplication, and we encourage customers into lower cost

channels where possible and compatible with citizen needs (such as

accessibility).

·

Citizen empowerment: we engage citizens directly in service design and delivery, and

provide them with technology tools that enable them to create public value

themselves.

·

Stakeholder communication: all our stakeholders - users, suppliers, delivery partners

elsewhere in the public, private and voluntary sector, politicians, the media,

etc. - have a clear understanding of our program and how they can engage with

it.

·

Cross-sectoral partnership: other market players (in the private, voluntary and community

sectors) often have much greater influence on citizen attitudes and behaviour

than government - so our strategy aims to build partnerships which enable the

market to deliver our objectives.

·

Skills mapping:

we know that the mix of business change, product and marketing management,

program management, and technology skills needed to deliver transformational

change does not already exist in our organisation. We have mapped out the

skills we need, and have a clear strategy for acquiring and maintaining them.

·

Skills integration: we have effective mechanisms in place to maximize value from the

skills available in all parts of our delivery team, bringing together internal

and external skills into an integrated team.

·

Smart supplier selection: we select suppliers based on long-term value for money rather than

price, and in particular based on our degree of confidence that the chosen

suppliers will secure delivery of the expected business benefits.

·

Supplier integration: we will manage the relationship with strategic suppliers at top

management level, and ensure effective client/supplier integration into an

effective program delivery team with shared management information systems.

·

Interoperability: Wherever possible we will use interoperable, open standards which are

well supported in the market-place.

·

Web-centric delivery: we will use SOA principles in order to support all of our customer

interactions, from face-to-face interactions by frontline staff to online

self-service interactions

·

Agility: we

will deploy technology using common building blocks which can be re-used to

enable flexible and adaptive use of technology to react quickly to changing

customer needs and demands.

·

Shared services: key building blocks will be managed as government-wide resources -

in particular common data sets (e.g. name, address); common citizen

applications (e.g. authentication, payments, notifications); and core ICT

infrastructure.

·

Phased implementation: we will avoid a "big bang" approach to implementation,

reliant on significant levels of simultaneous technological and organizational

change. Instead, we will develop a phased delivery roadmap which:

-

works with citizens and businesses to identify

a set of services which will bring quick user value, in order to start building

a user base

-

prioritise those services which can be

delivered quickly, at low cost, and low risk using standard (rather than

bespoke) solutions

-

works first with early adopters within the

Government organisation to create exemplars and internal champions for change

-

learns from experience, and then drives forward

longer term transformations.

·

Continuous improvement: we expect not to get everything right first time, but have systems

which enable us to understand the current position, plan, move quickly, and

learn from experience

·

Risk management: we need clarity and insight into the consequences of

transformation and mechanisms to assess risk and handle monitoring, recovery

and roll-back

·

Benefit realisation strategy: we have a clear strategy to ensure that all the intended benefits

from our Transformation Program are delivered in practice, built around the

three pillars of benefit mapping, benefit tracking and benefit delivery.

Component 3: Delivery Processes

Delivering the principles outlined in Component 1,

in line with the Critical Success Factors detailed in Component 2, involves

re-inventing every stage of the service delivery process. The Transformational

Government Framework identifies four main delivery processes, each of

which must be managed in a government-wide and citizen-centric way in order to

deliver effective transformation:

·

Business Management

·

Customer Management

·

Channel Management

·

Technology Management

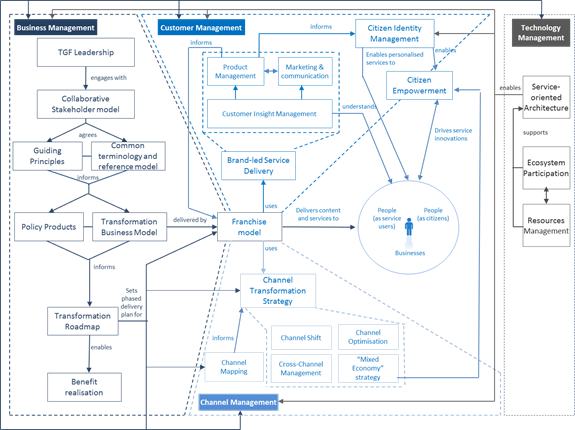

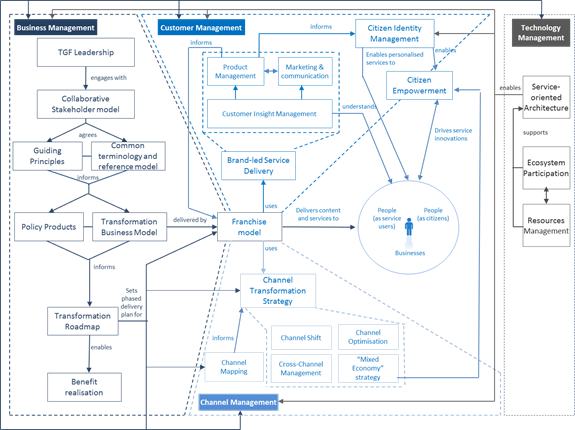

A high-level map of these delivery

processes and how their constituent elements interact is illustrated in summary

below. The following sections then look in more detail at each of the four

delivery processes, setting out the best practices which should be followed in

order to ensure conformance with the Transformational Government Framework.

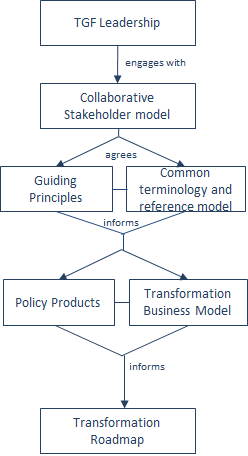

Figure 3: Relationships

between the four Delivery Processes for Transformational Government

Business

Management Framework

The Transformational Government Framework identifies six key aspects of

business management which must be tackled at the whole-of-government level:

Figure 4: Overview of the Business Management Framework

·

Transformational Government leadership: the key people and governance structures needed to develop and

implement a Transformational Government program;

·

A collaborative Stakeholder Governance Model:

the process by which all key stakeholders are identified, engaged and

buy-in to the transformation program;

·

A common terminology and Reference Model:

ensuring that all stakeholders have a clear, consistent and common understanding

of the key concepts involved in Transformational Government; how these concepts

relate to each other; how they can be formally modelled; and how such models

can be leveraged and integrated into new and existing information

architectures;

·

A Transformation Business Model: a new

virtual business layer within government, focused round the needs of citizens

and businesses (the “Franchise Marketplace”), which enables the existing

silo-based structure of government to collaborate effectively in understanding

and meeting user needs;

·

The development and management of Policy

Products: these documents formally define government-wide goals for

achieving government transformation and thus constitute the documented

commitment of any conformant agency to the transformational process;

·

A Transformation Delivery Roadmap:

giving a four to five year view of how the program will be delivered, with

explicit recognition of priorities and trade-offs between different elements of

the program.

|

Any conformant implementation of the TGF

Business Management Framework:

|

|

MUST have Leadership which

involves:

|

|

-

Clear accountability at both the political and

administrative levels

|

|

-

Deployment of formal program management

disciplines

|

|

-

A clearly identified mix of leadership skills

|

|

-

Engagement of a broad-based leadership team

across the wider government.

|

|

MUST have a Collaborative

Stakeholder Governance Model

|

|

MUST have an agreed and shared

terminology and reference model

|

|

MUST have a Transformation Business

Model

|

|

SHOULD use the Franchise

Marketplace Model

|

|

MUST use the Policy Product Map

to identify all necessary Policy Products

|

|

MUST have a phased Transformation

Roadmap

|

Further guidance on how

to implement this process is given in Part III (a) of the Primer.

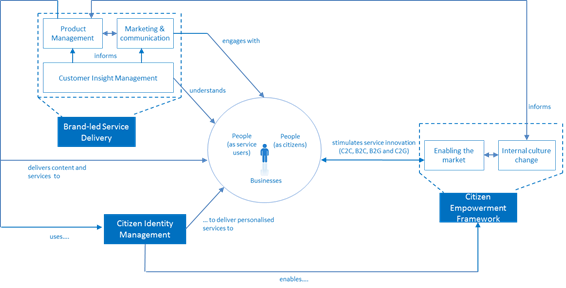

There are three key parts to the TGF Customer

Management Framework:

·

Brand-led Service Delivery: a user-focused framework for ensuring that:

-

Detailed insight is gathered into

citizen and business needs

-

This insight informs a brand-led product

management process covering all stages of government service design and

delivery

-

The brand values for Transformational

Government then drive all aspects of marketing and communications for

government services;

·

Identity Management: the business architecture, technical

architecture, and citizen-centric identity model needed to enable secure and

joined-up services which citizens and businesses will trust and engage with;

and

·

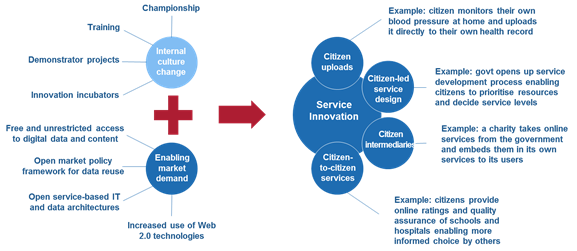

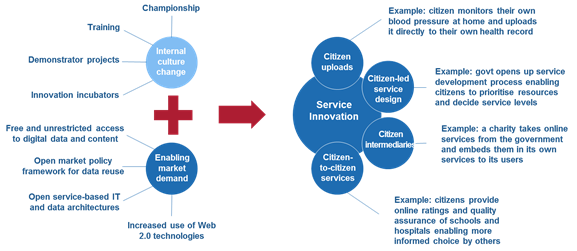

Citizen Empowerment: the internal cultural changes and external market-enabling actions

which enable governments to engage with citizens and businesses as active

co-creators of public services, rather than their passive recipients.

Figure 5: Overview

of the Customer Management Framework

|

Any conformant implementation of the TGF

Customer Management Framework:

|

|

MUST have a Brand-led Service

Delivery Strategy, which is agreed and managed at a whole-of-government

level and which addresses:

|

|

-

Customer Insight;

|

|

-

Product Management;

|

|

-

Marketing and communication;

|

|

MUST have a Citizen Identity

Management Framework, which:

|

|

-

uses a federated business model;

|

|

-

uses a service-oriented IT architecture;

|

|

-

is citizen-centric, giving citizens control,

choice and transparency over personal data;

|

|

MUST have a Citizen Empowerment

Framework, which encourages and enables service innovation in the

Citizen-to-Citizen, Business-to-Citizen, and Citizen-to-Government sectors.

|

Further guidance

on how to implement this process is given in Part III (b) of this TGF Primer.

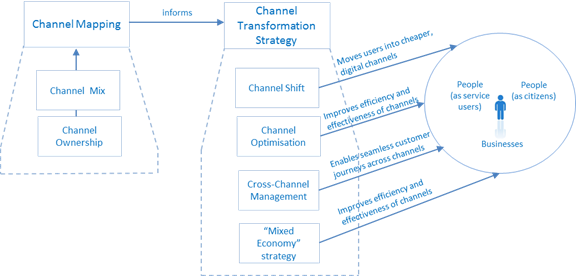

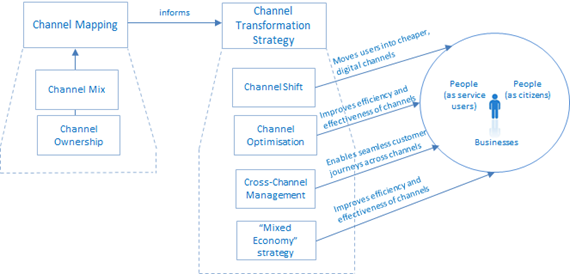

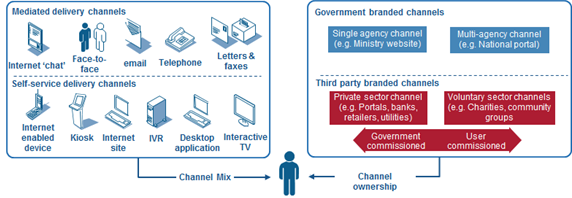

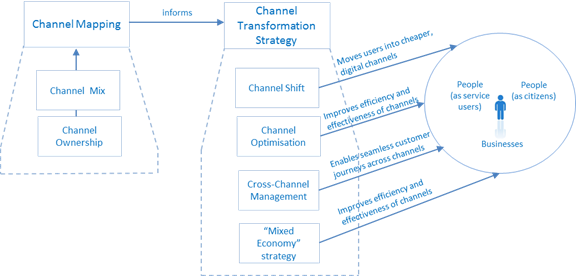

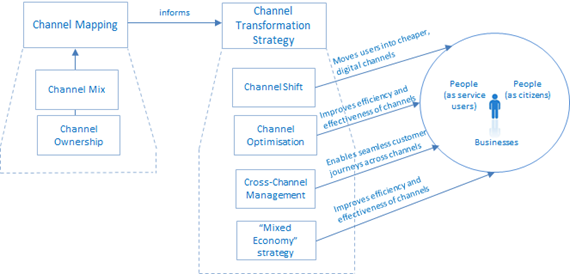

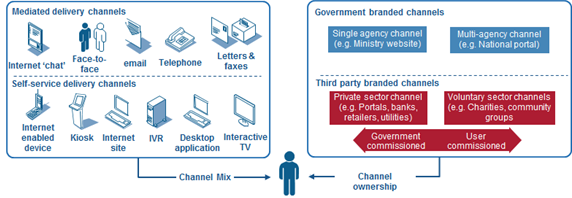

The two key parts of the Channel Management

Framework are:

·

Channel Mapping: a clear audit of what channels are currently used to deliver

government services. The TGF Channel Mapping approach includes an analysis of

these channels across two key dimensions: which delivery channels are being

used (‘channel mix’) and who owns them (‘channel ownership’).

·

Channel Transformation Strategy: building a new channel management approach centred around the

needs and behaviour of citizens and businesses. The key concerns of such an

approach include:

-

Channel Optimization;

-

Channel Shift;

-

Cross-Channel Management; and

-

development of a “Mixed Economy” in service

provision through private and voluntary sector intermediaries.

Figure 6: Overview of the

Channel Management Framework

|

Any conformant implementation of the Channel

Management Framework:

|

|

MUST have a clear mapping

of existing channels, and their cost structures

|

|

MUST have a Channel

Transformation Strategy which addresses the following elements:

|

|

-

Shifting service users into lower cost,

digital channels;

|

|

-

Optimising the cost and performance of each

channel, including through use of benchmarking;

|

|

-

Improving cross-channel management, with the

aim of providing a seamless user experience across different channels;

|

|

-

Developing a thriving mixed economy in the

delivery of government services by private and voluntary sector

intermediaries.

|

Further guidance on how to

implement this process is given in Part III (c) of this TGF Primer.

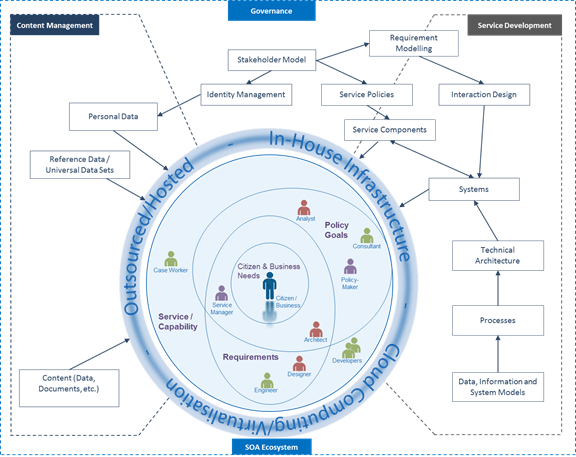

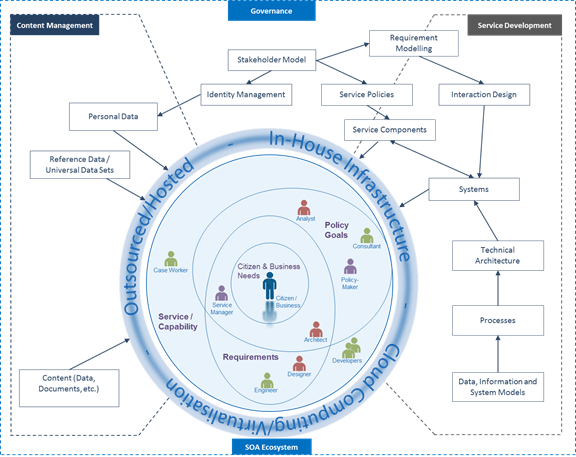

The elements of the TGF Technology Management

Framework are as follows:

·

Resources Management: the explicit

identification and management of all information and technology resources;

·

Ecosystem Participation: a clear model and

understanding of the stakeholders, actors and systems that comprise the overall

service ecosystem and their relationships to each other;

·

Realisation and governance of ICT systems based

on SOA principles

Figure 7: Overview

of the Technology Management Framework

|

Any conformant implementation of the Technology

Management Framework:

|

|

MUST manage

information and ICT system resources as distinct, valued assets including

issues related to the Identification, ownership, stewardship and usage

policies for each asset type;

|

|

MUST explicitly model the stakeholders, actors and systems that comprise the overall

service ecosystem and their relationships to each other

|

|

SHOULD maintain and

update the stakeholder model on a regular basis

|

|

MUST use the OASIS

‘Reference Model for SOA’ as the primary source for core concepts and

definitions of the SOA paradigm, including

|

|

-

A clear understanding of the goals,

motivations and requirements that any SOA-based system is intended to

address;

|

|

-

Identifiable boundaries of ownership of all

components (and identity of the components themselves) in any SOA ecosystem;

|

|

-

Discrete service realisation and re-use that

provides a capability to perform some work on behalf of another party;

|

|

-

The specification of any capability that is

offered for use by another party with clear service descriptions and

contracts

|

|

SHOULD consider the

OASIS ‘SOA Reference Architecture Framework’ when designing specific

SOA-based systems

|

Further guidance on how to

implement this process is given in Part III (d) of this TGF Primer.

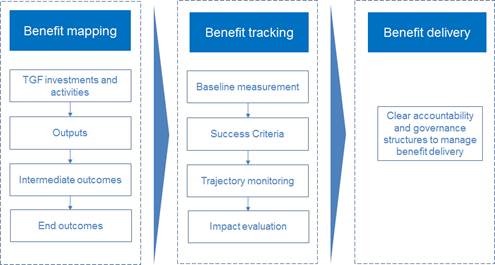

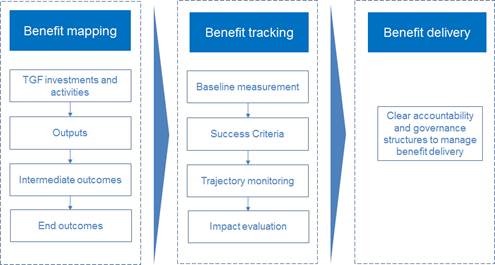

Component 4:

Benefit Realisation Strategy

The three parts of the TGF Benefit Realisation

Strategy are:

·

Benefit Mapping: which sets out all the intended outcomes from the transformation

program and gives visibility of how the outputs from specific activities and

investments in the program flow through to deliver those outcomes;

·

Benefit Tracking: which takes this a step further by baselining current performance

against the target output and outcomes, defining “smart” success criteria for

future performance, and tracking progress against planned delivery trajectories

aimed at achieving these success criteria; and

·

Benefit Delivery: which ensures that governance arrangements are in place to ensure

continued benefits after the initial transformation program is implemented.

The relationship between these parts and

conformance criteria for this element of the TGF are shown below.

Figure 8: Overview of the Benefit Realisation Strategy

|

Any conformant implementation of the Benefit

Realisation Strategy:

|

|

MUST clearly identify and quantify the impacts and outcomes that

implementation of the TGF aims to achieve

|

|

SHOULD ensure clear line-of-sight between every investment and

activity in the programme, the immediate outputs these produce, and the final

targeted outcomes

|

|

MUST establish clear and quantified baselines for the current performance

of target outputs and outcomes

|

|

MUST set measurable success criteria

|

|

SHOULD track progress against planned delivery trajectories for

each of the targeted outputs and outcomes

|

|

MUST establish clear accountability and governance structures to

manage benefit delivery

|

The Business Management Framework of the

TGF includes formal terminology and a reference model in order to ensure that

all stakeholders have a clear, consistent and common understanding of the key

concepts involved in Transformational Government; how these concepts relate to

each other; how they can be formally modelled; and how such models can be

leveraged and integrated into new and existing information architectures.

This enables any conformant agency to use a

common terminology without ambiguity and be sure that these terms are used

consistently throughout all work.

Some key concepts are already introduced

below. Further guidance on how the terminology is composed and how a reference

model may be used is given in Part III (a) of this Primer.

TGF Leadership, Stakeholders, Administrations and

Agencies

Leadership

Key people and governance structures needed to develop and implement

a Transformational Government program

Stakeholder

Any claimant inside or outside an organisation who have a vested

interest in any problem and/or its solution

Stakeholder Governance Model

Model and process in which key stakeholders are identified, engaged

and buy-in to the transformation program

Transformation Business Model

Delivery Roadmap

A detailed multi-year plan for the delivery of an overall

cross-government vision for service transformation

Transformational Government

A managed, citizen-centred, process of ICT-enabled change in the

public sector

Policy formulation and Policy Products

Goal

A broadly stated, unmeasured but desired outcome. Not to be confused

with an Objective

Need

A general statement expressed by a stakeholder of something that is

required. Not to be confused with a Requirement

Objective

A specific, measurable and achievable outcome that a participant

seeks to achieve

Policy Product

A document that has been formally adopted

on a government-wide basis and aimed at helping achieve one or other goal of

citizen service transformation

Requirement

A formal statement of a desired result

that, if achieved, will satisfy a need

Service delivery and the Franchise Marketplace Model

Accessibility

A policy prescription that aims at ensuring that people with

disabilities and the elderly can use public services with the same service

levels as all other citizens.

Channel

A particular means and/or path of delivery of a service to a

customer

Customer Franchise

A collaborative organisation created by

the government with the purpose of: understanding the needs of a specific

customer segment for government services (such as, for example, parents,

motorists, disabled people, land and property); championing the needs of that

segment within government; aggregating content and transactions for that

segment from across government and beyond; and delivering that content and

services as part of the wider Franchise Marketplace.

Franchise Marketplace

The virtual business infrastructure within which Customer Franchises

collaborate with each other and other stakeholders to deliver user-centric,

trusted and interoperable content and transactions to citizens and businesses.

The Franchise Marketplace is the business model recommended by the TGF for best

delivering the TGF Guiding Principle of “Build services around customer needs,

not organisational structure”.

Delegate

Some person or agent acting with authority on behalf of another

person.

Inclusion

A policy prescription that aims at allowing everyone to take full

advantage of the opportunities offered by new technologies to overcome social

and economic disadvantages and exclusion.

SOA and Technology Infrastructure

Ecosystem

A set of ICT systems and stakeholders together with the environment

and context within which they all operate

Interoperability

The ability of disparate and diverse organisations to interact

towards mutually beneficial and agreed common goals, involving the sharing of

information and knowledge between the organisations, through the business

processes they support, by means of the exchange of data between their respective

ICT systems.

Security

The set of mechanisms for ensuring and enhancing trust and

confidence in a system.

Service-Orientation, Service-Oriented

A paradigm for organizing and utilizing distributed capabilities

that may be under the control of different ownership domains.

System

A collection of components organized to

accomplish a specific function or set of functions

A consolidated view of the conformance

criteria described in the TGF is given below. Any conformant implementation of

this Framework:

1.

MUST use the Guiding

Principles set out in Component 1 of the TGF

2.

MUST have delivery processes for business

management, customer management, channel management and technology management which address the best practices described in Component 2 of the

TGF. Specifically, this means:

a) A

Business Management Framework which:

·

MUST have Leadership which involves:

Clear

accountability at both the political and administrative levels;

-

Deployment of formal program management

disciplines;

-

A clearly identified mix of leadership skills;

-

Engagement of a broad-based leadership team

across the wider government.

·

MUST have a Collaborative

Stakeholder Governance Model

·

MUST have an

agreed and common terminology and reference model

·

MUST have a Transformation

Business Model

·

SHOULD use the Franchise

Marketplace Model

·

MUST use the Policy

Product Map as a tool to help identify Policy Products needed within the

relevant government

·

MUST have a phased Transformation Roadmap

b) A

Customer Management Framework which:

·

MUST have a

Brand-led Service Delivery Strategy, which is agreed and managed at a

whole-of-government level and which addresses:

Customer

Insight

Product

Management

-

Marketing and communication

·

MUST have a Citizen

Identity Management Framework, which:

Uses a

federated business model

Uses a

service-oriented architecture (as part of the wider SOA described in the TGF

Technology Management Framework)

-

Is citizen-centric, giving citizens control,

choice and transparency over personal data

·

MUST have a Citizen

Empowerment Framework, which encourages and enables service innovation in

the Citizen-to-Citizen, Business-to-Citizen, Citizen-to-Government, and

Business-to-Government sectors

c) A

Channel Management Framework which:

·

MUST have a

clear mapping of existing channels, and their cost structures

·

MUST have a Channel Transformation Strategy

which addresses the following elements:

Shifting

service users into lower cost, digital channels

Optimising

the cost and performance of each channel, including through use of benchmarking

Improving

cross-channel management, with the aim of providing a seamless user experience

across different channels

-

Developing a thriving mixed economy in the

delivery of government services by private and voluntary sector intermediaries.

d) A

Technology Management Framework which:

·

MUST manage

information and ICT system resources as distinct, valued assets including

issues related to the Identification, ownership, stewardship and usage policies

for each asset type;

·

MUST explicitly

model the stakeholders, actors and systems that

comprise the overall service ecosystem and their relationships to each other

·

SHOULD maintain

and update the stakeholder model on a regular basis

·

MUST use the

OASIS ‘Reference Model for SOA’ as the primary source for core concepts and

definitions of the SOA paradigm, including

-

A clear understanding of the goals, motivations

and requirements that any SOA-based system is intended to address;

-

Identifiable boundaries of ownership of all

components (and identity of the components themselves) in any SOA ecosystem;

-

Discrete service realisation and re-use that

provides a capability to perform some work on behalf of another party;

-

The specification of any capability that is

offered for use by another party with clear service

descriptions and contracts

3.

MUST measure and manage the Critical

Success Factors outlined in Component 3 of the TGF

4.

SHOULD seek regular, independent review

of performance against these Critical Success

Factors

5.

MUST have a Benefit Realisation Strategy which addresses the areas of benefit mapping, benefit tracking and

benefit delivery as described in Component 4 of the TGF

In terms of the primary users identified for the

TGF in Part I:

·

A conformant government will be able to

demonstrate and document that it is engaged in a Transformation Program which

complies with all these criteria.

·

A conformant private-sector organisation will

be able to demonstrate and document that it provides products and services

which help governments to comply with all these criteria.

This part of the TGF Primer sets out some initial

guidance to help TGF users understand and implement the TGF, focusing in

particular on:

·

The TGF Business Management Framework

·

The TGF Customer Management Framework

·

The TGF Channel Management Framework

·

The TGF Technology Management Framework

·

TGF Terminology.

We envisage issuing further guidance over

time, but this initial set of guidance notes is intended to give a deeper view

of the context for these major elements of the TGF, and to highlight best

practice approaches to its implementation.

The TGF Business

Management Framework is in four main sections:

·

Context

·

Overview of key components in the TGF Business

Management Framework

·

Detailed description of and guidance on the key

components

For largely historical

reasons, governments are generally organised around individually accountable

vertical silos (for example, tax, health, transport) with clear demarcations

between central, regional, and local government. Even within a particular tier

of government, several organisations can have responsibility for different

aspects of the same person, same asset or same process. Yet citizen and

business needs cut across these demarcations. In moving to a customer-centric

approach, it is vital to redress this fragmented approach to business

management, and to put in place business management processes which operate at

the whole-of-government level.

The Transformational

Government Framework identifies six key aspects of business management which

need to be tackled in this way:

·

Transformational Government leadership: the key people and governance structures needed to develop and implement

a Transformational Government program

·

A collaborative Stakeholder Governance

Model: the process by which all key stakeholders are identified, engaged

and buy-in to the transformation program, including to the Guiding Principles

described in Component 1 of the TGF

·

A common terminology and reference

architecture: ensuring that all stakeholders have a clear, consistent and

common understanding of the key concepts involved in Transformational

Government and how these inter-relate

·

A Transformation Business Model: a new

virtual business layer within government, focused round the needs of citizens

and businesses, which enables the existing silo-based structure of government

to collaborate effectively in understanding and meeting user needs

·

The development and management of Policy

Products that constitute the documented commitment to the transformational

process of any conformant agency

·

A Transformation Delivery Roadmap:

giving a four to five year view of how the program will be delivered, with

explicit recognition of priorities and trade-offs between different elements of

the program.

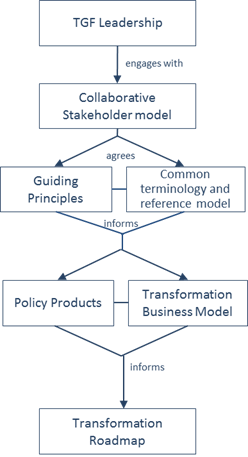

A high level view of the logical

relationships between these components is illustrated below.

Figure 9: Key components of the Business Management Framework

Transformation programs require sustained

leadership over a period of years.

There is no “ideal” leadership structure for a

transformation program: the optimal positioning of the leadership team will

depend on the context of each specific government. However, global experience

suggests the following factors are vital to address in whichever way is most

appropriate for the specific context:

·

A clear focus of accountability: at both the political and administrative levels there should be an

explicit functional responsibility for the Transformation Program. These

functions should be occupied by individuals with sufficient authority to

command the resources and mobilise the support necessary to fulfil this

mission.

·

Deployment of formal program management

disciplines: to deliver effective‑Government-wide transformation, it

is vital to use a formalised program management approach, such as PRINCE 2.

·

Ensuring the right skills mix in the

leadership team. Effective leadership of a Transformation Program requires

the senior accountable leaders to have access to a mix of key skills in the

leadership team which they build around them, including: strategy development

skills, stakeholder engagement skills, marketing skills, commercial skills and

technology management skills. Deployment of a formal competency framework such

as SFIA can be helpful in identifying and building the right skill sets.

·

Building a broad-based leadership team

across the wider government. It is not essential that all Ministers and senior

management are committed to the transformation program from the outset. Indeed,

a key feature of an effective roadmap for transformation is that it nurtures

and grows support for the strategy through the implementation process. However,

it is important that the program is seen not simply as a centralised or

top-down initiative. Sharing leadership roles with senior colleagues across the

Government organisation is therefore important. Further detail on this is set

out in the section below on a collaborative stakeholder model.

Development and delivery of an effective Transformational

Government program requires engagement with a very wide range of stakeholders,

not only across the whole of government but also with the private sector,

voluntary and community sectors as well as with business and citizen users of

public services. A significant effort is needed to include all stakeholders in

the governance of the Transformational Government program at an appropriate and

effective level.

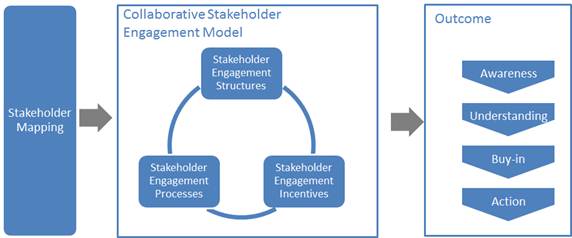

Key elements are set out below that a

conformant TGF program will need to address in developing its Collaborative

Stakeholder Governance Model, if it is to engage successfully with stakeholders

and align them effectively behind shared objectives. Each of these elements is

then discussed in more detail.

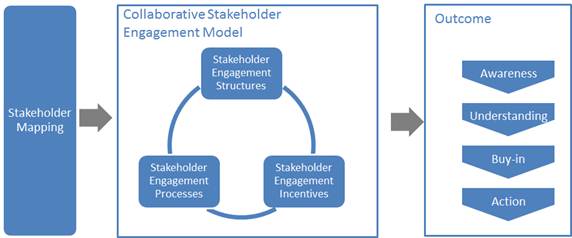

Figure 10: Overview

of Collaborative Stakeholder Governance

Stakeholder Mapping

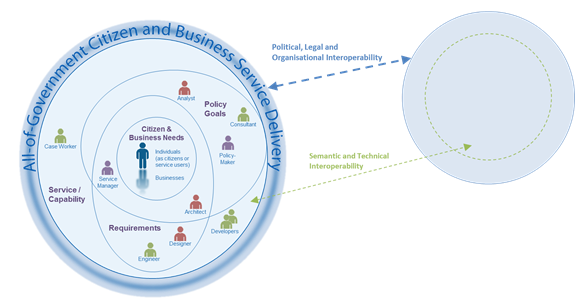

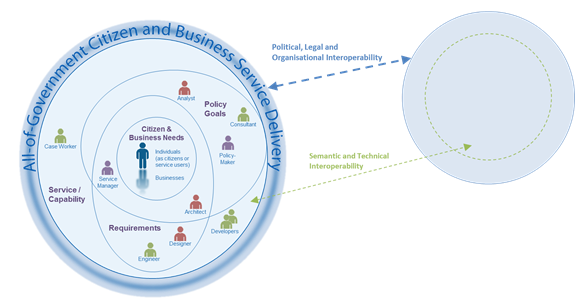

It is vital to describe and map the

complete landscape of relevant stakeholders. The

Transformational Government Framework puts the individual – whether as a

citizen or as someone acting within a business or other role – at the centre:

Figure 11: Landscape of some key stakeholders

This view deliberately and completely avoids the

rather generic concept of ‘User’ that is dominant in traditional IT stakeholder

engagement models, preferring rather to identify the different interests and

concerns that are at stake (the mauve labels) and the key groups of

stakeholders (the different people icons) in the development of any service.

The figure is by no means complete nor the

only ‘valid’ view. It seeks instead to illustrate that the process of

transformation requires reappraisal of the current set-up and assessment of

what needs to change.

By clearly separating out key stakeholder groups

and starting to understand and articulate their specific concerns as

stakeholders (any individual’s role may vary according to context:

in one situation, a person is a parent; in another, a policy-maker; or another,

a service provider), we can start to understand how stakeholders relate (in

different roles): to each other; to various administrations and services

involved; to policy drivers and constraints; and how these all come together in

a coherent ecosystem supported by a Transformational Government Framework. In

this view,

·

A service (or ICT capability made

available as a service) is understood as responding to a set of requirements

and policy goals (some of which overlap) – stakeholders concerned at this level

include, for example, case workers in a public administration or developers who

have worked with them in delivering a specific service;

·

Requirements

encapsulate and formalise vaguely stated goals and needs of citizens and

businesses and take on board the policy goals of the political sponsor or

champion – stakeholders at this level include, for example, managers of public

service who can articulate the needs of their respective services, the

information and systems architects who capture those needs as formal

requirements that engineers can work with to develop services;

·

Policy Goals

capture the high-level concerns and priorities of the political authorities and

continually assess how these goals reflect key citizen and business concerns –

stakeholders include policy makers and senior management as well as consultants

and analysts involved in helping identify technology and administrative trends

that can be used to leverage those goals; and finally;

·

Citizen and Business Needs that,

ultimately, can only be fully understood by the people concerned themselves –

nonetheless stakeholders at this level can also include citizen or business

associations, consumer and other interest groups who engage with policy makers

to advance the interests of certain groups with distinct needs and are able to

articulate those needs in ways that can be used by analysts and consultants.

The various ellipses in the diagram above

are deliberately not concentric circles. This is to underline that the process

of establishing a service or capability is not a linear one going from needs,

goals and requirements. In reality stages are often inter-related.

The mapping of stakeholders and their

principal concerns at a generic level is used as a key input to the TGF

reference model outlined in the next section and that needs to be validated

within any TGF program. It is valuable as a tool for encouraging collaborative

governance as it renders explicit many of the relationships and concerns that

are often left implicit but nonetheless impact on an organisation’s ability to

reflect stakeholders’ concerns.

The Stakeholder Engagement Model

However, it is not enough simply to map and

understand stakeholder relationships and concerns. An effective TGF program

will also address the three other dimensions of the model illustrated above:

·

Stakeholder Engagement Structures: the organisational arrangements put in place to lead the

transformation programme, e.g.:

central unit(s)

governance boards

-

industry partnership board

·

Stakeholder Engagement Processes: the processes and work flows through which the TGF Leadership and

the different TGF Stakeholders interact, e.g.:

reporting and accountability

processes

risk management processes

issue escalation processes

consultation processes

-

collaborative product development processes.

·

Stakeholder Incentives: the set of levers available to drive change through these

governance structures and processes. These will vary by government, but

typical levers being deployed include:

central mandates

political leadership

administrative championship

personal performance incentives for

government officials

-

alignment between public policy objectives and

the commercial objectives of private sector partners.

There is no one right model for doing this

successfully, but any conformant TGF program needs to make sure that it has

used the framework above to define its own Collaborative Stakeholder Engagement

Model which explicitly articulates all of these elements: a comprehensive

stakeholder map, coupled with the structures, processes and incentives needed

to deliver full understanding and buy-in to the program, plus effective

stakeholder action in support of it.

Collaboration between TGF Programs

The model clearly focuses attention within

any specific TGF program. However (and increasingly) collaboration is required

also between governments and, by implication, between TGF programs.

In the figure below, we see that

collaboration between TGF programs is favoured at the political, legal and

organisational levels and only later, if and when necessary, at the more

‘tightly-coupled’ semantic and technical levels.

Figure 12: Collaboration

between TGF programs through different levels of Interoperability

This approach is also consistent with the

SOA paradigm for service development – not only are requirements defined and

services offered independently of any underlying technology or infrastructure

but also one TGF program can be seen (and may need to be seen) as a ‘service

provider’ to another TGF program’s ‘service request’. For example, a business

wishing to establish itself in a second country may need to provide

authenticated information and credentials managed by government or business in

the first country.

A further advantage of this approach is

that it becomes easier to identify and manage high level government

requirements for services: whether in the choice of ICT standards that may need

to be used to address a particular technology issue or determining the criteria

for awarding public procurement contracts, this approach allows a

‘loose-coupling’ at the level of clearly defined high-level policy needs rather

than the more tightly-coupled and often brittle approach of specifying

particular technologies, software or systems.

In any change program of this breadth and complexity,

it is vital that all stakeholders have a common understanding of the key

concepts involved and how they interrelate, and have a common language to

describe these in.

We therefore recommend that a

TGF-conformant transformation program should seek to agree with stakeholders a

common Terminology and Transformation Reference Model.

Why have a terminology and reference model?

In everyday life, we use terms

– ‘citizen’, ‘need’, ‘service’ – as common, often implicitly accepted labels

for concepts. The concept is the abstract mental idea (which

should be universal and language independent) to which the term gives a

material expression in a specific language. Particularly in an international

environment such as global standardization initiatives, the distinction is

important as it is common concepts that we wish to work with, not common terms.

This distinction also helps avoid common

modelling pitfalls. Terms that may seem similar or the same across two or more

languages may actually refer to different concepts; or a single term in one

language could be understood to refer to more than one concept which another

language expresses with discrete terms: For example, the

English term ‘service’ can refer to different concepts - an

organisational unit (such as ‘Passport Service’) or something that is performed

by one for another (such as ‘a dry cleaning service’), whereas discrete terms

are used for the discrete concepts in German (‘Dienst’ or ‘Dienstleistung’). As

the TGF is intended for use anywhere in the world, it is important to ensure

that (ideally) global concepts can be transposed and translated and thus

understood in other languages: we therefore need to associate an explicit

definition with each concept as we do in a dictionary. The TGF uses the structure

and methodology of an existing international standard to create its terminology

Concepts do not exist in isolation,

however. It is the broader understanding of the relationships between concepts

that give those concepts fuller meaning and allow us to model our world, our

business activities, our stakeholders, etc. in a way that increases the chance

that our digital systems are an accurate reflection of our work. In information science, an ontology is a formal representation of

knowledge as a set of concepts within a domain, and the relationships between

those concepts. It can be used to describe the domain (the coverage should be

sufficiently comprehensive to include all concepts relevant to the domain) and

to reason about the domain.

The TGF does not include a formal ontology

but is sufficiently clear in its concepts, definitions and relationships

between concepts that the Framework will use consistently as an internally

coherent set. It does include however a “reference model” that is clear enough

that subsequent ontology development is possible if so desired.

The TGF Primer already includes formal

definitions of key concepts used throughout the Framework and a complete

terminology and reference model – that formalizes the concepts and the

relationships between them – is prepared as a separate deliverable.

Weaknesses of current models

A central task of the TGF leadership and

collaborative stakeholder model is to develop a new and effective business

model which enables the machinery of government to deliver citizen-centric

services in practice.

It is failure to address this requirement

for a new business model which, arguably, has been the greatest weakness of

most traditional e‑Government programmes. For the most part, the transition

to e‑Government has involved overlaying technology onto the existing

business model of government: a business model based around unconnected silos -

in which policy-making, budgets, accountability, decision-making and service

delivery are all embedded within a vertically-integrated delivery chain based

around specific government functions. The experience of governments around the

world over the last two decades is that this simply does not work.

So what is the new business model which is

required to deliver citizen service transformation? Many attempts have been

made by governments to introduce greater cross-government coordination, but

largely these have been "bolted on" to the underlying business model,

and hence experience only limited success.

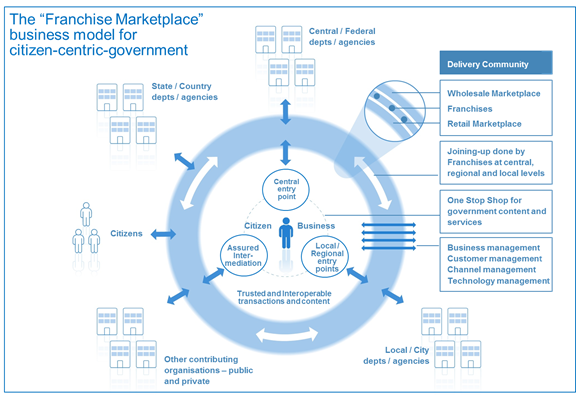

The Franchise Marketplace Model

This Framework recommends implementation of a business model which

permits the joining-up of services from all parts of government and external

stakeholders in a way that makes sense to citizens and businesses, yet without

attempting to restructure the participating parts of government. Conceptually,

this leads to a model where the existing structure of government continues to

act as a supplier of services, but intermediated by a "virtual"

business infrastructure based around customer needs. A top-level view of such a

virtual, market-based approach to citizen service transformation is set out in

the figure below:

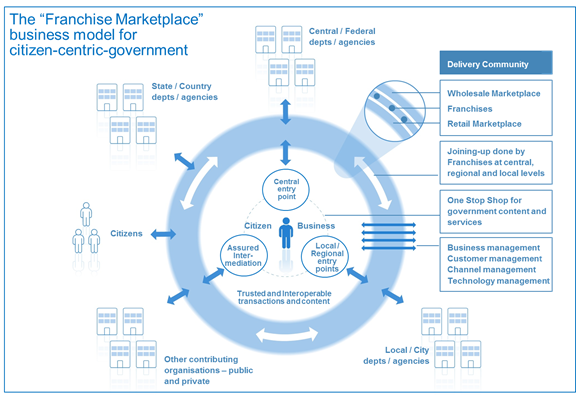

Figure 13: Overview of the Franchise Marketplace

Key features of this business model are:

·

The model puts into place a number of agile

cross-government virtual "franchise businesses" based around customer

segments (such as, for example, parents, motorists, disabled people). These

franchises are responsible for gaining full understanding of their customers'

needs so that they can deliver quickly and adapt to changing requirements over

time in order to deliver more customer centric services - which in turn, is

proven to drive higher service take-up and greater customer satisfaction.

·

Franchises provide a risk-averse operational

structure that enables functionally-organised government agencies at national,

regional and local to work together in a customer-focused "Delivery

Community". They do this by :

-

Enabling government to create a

"virtual" delivery structure focused on customer needs

-

Operating across the existing structure of

Government (because they are led by one of the existing "silos") and

resourced by organisations that have close links with the relevant customer

segment including, possibly, some outside of government

-

Dividing the task into manageable chunks

-

Removing a single point of failure

-

Working to a new and precisely-defined

operating model so as to ensure consistency

-

Working across and beyond government to manage

the key risks to citizen-centric service delivery

-

Acting as change agents inside‑Government

departments / agencies.

·

The model enables a "mixed economy"

of service provision:

-

firstly, by providing a clear market framework

within which private and voluntary sector service providers can repackage

public sector content and services; and

-

secondly by deploying ‘Web 2.0’ type approaches

across government that promote re-use and ‘mash-ups’ of existing content and

services, to make this simpler and cheaper at a technical level.

·

The whole model is capable of being delivered

using Cloud Computing

This Franchise model represents an

important break-through in the shift from a traditional e‑Government

approach towards citizen service transformation. Certainly, the model as a

whole or key elements of it has been adopted successfully in governments as

diverse as the UK, Hong Kong, Croatia, Abu Dhabi and Australia (where it has

been adopted by both the South Australia and Queensland governments).

It is clearly possible that alternate

models may develop in future. But however the Transformational Government

agenda develops, every government will need to find some sort of new business

model along these lines, rather than continue simply to overlay technology onto

an old silo-based business model built for an un-networked world.

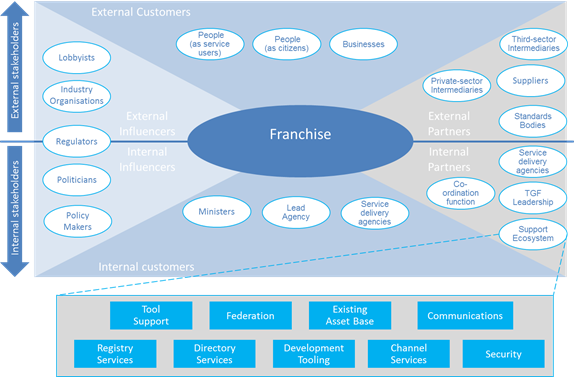

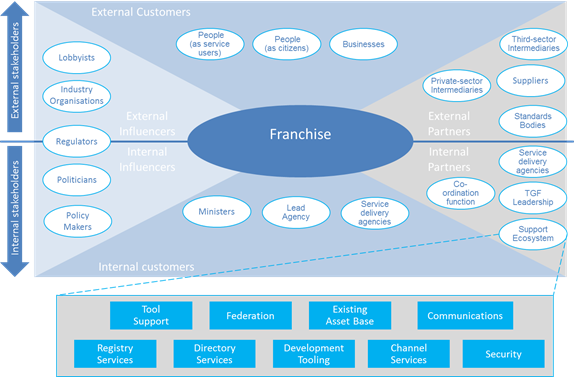

A number of relationships need to be managed by a

franchise to enable it to develop, maintain and deliver transformational

citizen-centric services. These represent different viewpoints that can be

broadly classified as:

·

Customers:

Those citizens and businesses to whom the franchise delivers content and

services, plus those internal stakeholders to whom the franchise provides a

service within the government.

·

Partners:

Those who are actors in the normal operation and delivery of the service, both

internally and externally to the government.

·

Influencers: those

who have a political, business or altruistic interest in the service and the

part that it plays in broader government, business and social scenarios.

·

Internal Customers: Those who work with the franchise to develop and maintain the

service.

Figure 14: Relationships in the Franchise Marketplace

The Franchise

The franchise is based around a customer

segment. It may contain bodies drawn from central, regional, and state

government and others that contribute to serving that segment.

It MUST have a lead organisation that

ensures its interests are represented to other franchises and bodies. It MUST

also have sponsoring organisations that with a responsibility for the full

range of service perspectives across the segment.

The franchise is responsible for ensuring

that all relationships with external bodies are managed and for the provision

of supporting assets necessary to allow organisations within the franchise and

working with it to discharge their responsibilities in an open, consultative

and transparent manner.

Despite the importance of the franchise

concept, it is not intended to add unnecessary bureaucracy – rather, it is

intended to provide a lightweight framework within which participants can work

naturally and cooperatively.

Customers

Customers are the most important actors in

operational services as the services MUST address their needs and those of the

people that they represent.

Thus, as well as being users, it is

essential that they are consulted during the proposal stage for all services.

Once operational, this group SHOULD to be involved in customer satisfaction

exercises and the development of any service enhancements to ensure that their

needs continue to be met.

It is vital that Franchises identify their

internal government customers and apply similar customer research and customer

satisfaction measurement to these internal customer relationships as well as to

external ones.

Partners

Many partners will be involved in helping the

Franchise effectively to deliver the requirements of its customer segment. The

partnership may involve:

·

working with the franchise to develop and

maintain the service

·

providing the supporting assets which give a

technical underpinning for this and other services.

The supporting assets provide the technical

underpinning for project delivery. Where they are publically owned, it is

intended that they will provide light-touch governance and facilities

(primarily technical) to support franchises and inter-working between them and

with standards bodies.

It is essential that they ensure the

provision and availability of assets that are universal (i.e. fundamental items

that are required by all public sector organisations) or common (i.e. assets

used across multiple franchises).

Tooling SHOULD to be provided with the aim

of supporting all stakeholders and facilitating their collaboration.

Influencers

The influencers are those who identify, and

possibly mandate, the need for a service. Accordingly, it is vital that they

are able to steer developments within and across franchises. They also have a

responsibility to ensure that all stakeholders are aligned and are

organisationally capable of discharging their responsibilities.

We define a "Policy Product" as:

any document which has been formally adopted on a government-wide basis in

order to help achieve the goals of citizen service transformation. These

documents vary in nature (from statutory documents with legal force, through

mandated policies, to informal guidance and best practice) and in length (some

may be very lengthy documents; others just a few paragraphs of text). Policy

Products are important drivers of change within government: first because the

process of producing them, if managed effectively, can help ensure strategic

clarity and stakeholder buy-in; and second because they then become vital

communication and management tools.

Over recent years, several governments have

published a wide range of Policy Products as part of their work on

Interoperability Frameworks and Enterprise Architectures, and other governments

are therefore able to draw on these as reference models when developing their

own Policy Products. However, we believe that the set of Policy Products

required to ensure that a holistic, government -wide vision for transformation

can be delivered is much broader than is currently being addressed in most

Interoperability Frameworks and Enterprise Architectures.

A TGF-conformant transformation program will use the matrix shown

below to create a map of the Policy Products that are needed to deliver the

program effectively. This matrix maps the four delivery processes described in

Component 2 of the TGF (Business Management, Customer Management, Channel Management

and service-oriented Technology Management) against the five interoperability

domains identified in what is currently the broadest of Interoperability

Frameworks - the European Interoperability Framework (EIF): technical,

semantic, organisational, legal and policy interoperability. While the EIF

framework is conceptually complete, by mapping it against these core delivery

processes, a much clearer sense can be gained of the actions which are needed.

|

The TGF

Policy Product Map

|

Political Interoperability

|

Legal Interoperability

|

Organisational

Interoperability

|

Semantic Interoperability

|

Technical

Interoperability

|

|

Business Management

|

Strategic Business Case for

overall Programme

|

Legal vires for inter-agency

collaboration

|

Benefits Realisation Plan

|

Business Process Model

|

Technology roadmap

|

|

Customer Management

|

Identity Management Strategy

|

Privacy, data protection and data

security legislation

|

Federated trust model for cross-agency

identity management

|

Common data standards

|

Single sign-on architecture

|

|

Channel Management

|

Intermediaries Policy

|

Pro-competitive regulatory framework

for the telecoms sector

|

Channel Management guidelines

|

Web accessibility guidelines

|

Presentation architecture

|

|

Technology Management

|

Information Security policy

|

Procurement legislation

|

Service level agreements

|

Physical data model

|

Interoperability Framework

|

Figure 15: A Policy Product Map completed with examples of individual policy

products. Each cell in the matrix may contain one or more policy products

depending on the outcome of relevant analysis

A full analysis of the Policy Products which we recommend are

typically needed to deliver an effective and holistic transformation program

will be included in a separate Committee Note “Tools and Models for the

Business Management Framework”. Although the detailed Policy Products in that

note are advisory and not all of them may be needed, any conformant

transformation program MUST use the overall framework and matrix of the Policy

Product Map in order to conduct at minimum a gap analysis aimed at identifying

the key Policy Products needed for that government, taking the Committee Note

into account as guidance.

Finally, it is essential that the vision,

strategy, business model and policies for citizen service transformation are

translated into an effective Transformation Roadmap.

Since everything can clearly not be done at

once, it is vital to map out which elements of the transformation programme

need to be started immediately, which can be done later, and in what order.

There is no one-size-fits all strategy which governments can use, since

strategy needs to be tailored to the unique circumstances of each government's

situation.

However, all governments face the same

strategic trade-offs: needing to ensure clear line-of-sight between all aspects

of programme activity and the end outcomes which the Government is seeking to

achieve, and to balance quick wins with the key steps needed to drive longer

term transformation.

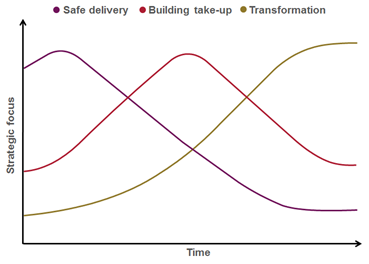

In the early days of the Transformational

Government program, we recommend that the major strategic focus should be on safe

delivery - that is, prioritising high benefit actions which help to

accelerate belief and confidence across the Government and the wider

stakeholder community that ICT-enabled change is possible and beneficial - but

which can be delivered with very low levels of risk. As the programme develops,

and an increasing number of services become available, the strategic focus can

move towards building take-up: that is, building demand for online

services and creating a critical mass of users. Once that critical mass starts

to appear, the strategic focus can start to shift towards fuller transformation:

in other words, to start driving out some of the more significant

transformational benefits that high levels of service take-up enables, for

example in terms of reducing the cost of government service delivery.

|

|

|

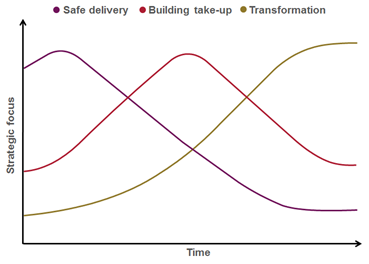

As the diagram below makes clear, these strategic foci are

not mutually exclusive, but overlap. Crucially, in the Safe Delivery phase

there will also be some vital steps needed in order to pave the way for longer

term transformation, particularly in respect of establishing the business case

for transformation, and embedding the strategy in effective governance

processes. But the diagram shows how the strategic weight between each

consideration should shift over time.

Figure 16: Roadmap priorities over

time

Guided by the strategic trade-off framework

described above, experience shows that a phased approach is the most

successful. Typically, an effective Delivery Roadmap will cover five main

phases.

The preparation and planning needed to develop a

tailored Delivery Roadmap for the Government, to ensure that the business case

for transformation is fully articulated, and that all key stakeholders are

on-board. Key outputs from this phase should include:

·

Transformation vision: a high level document

setting out the agreed future model for transformation of our client

organisation and its re-engineered business processes

·

Strategic business case: the key costs and

benefits associated with the transformation programme

·

Delivery roadmap: a multi-year transformation

plan, covering, among other things:

-

A change management plan (including

communication and training plans)

-

Central capability building and governance

processes

-

A sourcing strategy

-

A strategy for moving towards a service

oriented ICT architecture

-

A risk management strategy

-

A high level benefit realisation plan, setting

out the actions needed to ensure full downstream delivery of the intended benefits

from the transformation programme.

In this first phase of delivery, the focus is on

building the maximum of momentum behind the Roadmap for the minimum of delivery

risk. This means focusing in particular on three things:

·

some early quick wins to demonstrate progress

and early benefits, for a minimum of delivery risk and using little or no

technology expenditure

·

embedding the Roadmap in governance structures

and processes which will be needed to inform all future investments, notably

the frameworks of enterprise architecture, customer service standards and

issue/risk management that will be required

·

selecting effective delivery partners.

In this

phase, some of the more significant investments start coming on stream - for

example, the first version of the major "one-stop" citizen-facing

delivery platforms, and the first wave of transformation projects from

"champion" or "early adopter" agencies within the

Government

In this phase, the focus shifts towards

driving take-up of the initial services, expanding the initial one-stop service

over more channels, learning from user feedback, and using that feedback to

specify changes to the business and technology architectures being developed as

longer term, strategic solutions

Finally, the program looks to build out the broader range of

e-transformation projects, drive forward the migration of all major

citizen-facing services towards the new one-stop channels, and complete the

transition to the full strategic IT platform needed to guarantee future agility

as business and customer priorities change.

The TGF Customer

Management Framework is in three main sections:

·

Context

·

Overview of key components in the TGF Customer

Management Framework

·

Detailed description of and guidance on the key

components

The first of the Guiding

Principles identified in Component 1 of the TGF is:

“Develop

a detailed and segmented understanding of your citizen and business customers:

·

Own the

customer at the whole-of-government level;

·

Don't

assume you know what users of your services think - research, research,

research;

·

Invest

in developing a real-time, event-level understanding of citizen and business

interactions with government”

Putting these principles into practice involves

taking a holistic, market-driven approach to every step of the service design

and delivery process. This in turn often requires new skills and management

practices to be brought into government. The TGF Customer Management Framework

draws together best practice on how to do this.

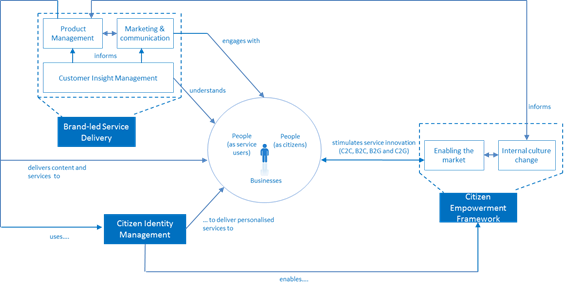

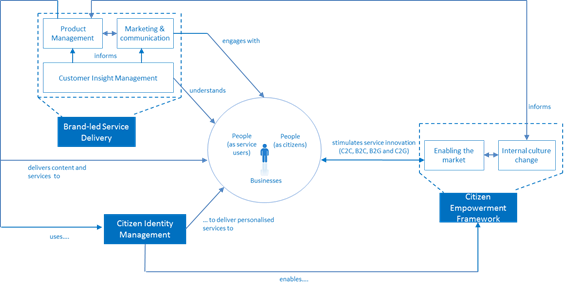

There are three key

components of the TGF Customer Management Framework:

·

Brand-led Service Delivery

·

Identity Management

·

Citizen Empowerment

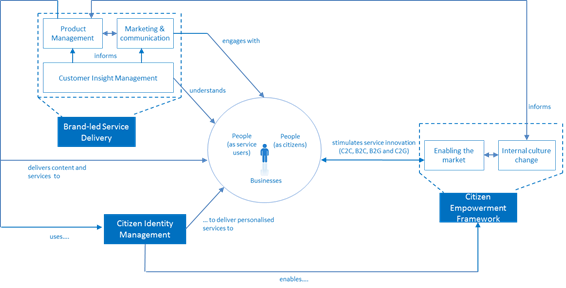

A high level view of the logical

relationships between these components is illustrated below.

Figure 17: Overview

of the Customer Management Framework

Marketing is critical to effective citizen

service transformation, yet is something at which government traditionally does

not excel. Often, marketing is fundamentally misunderstood within government -

as being equivalent to advertising or perhaps, more broadly, as being

equivalent to communication.

Properly understood, however, marketing is the

process of:

·

Understanding the target market for government

services in all its breadth and complexity

·

Learning what is needed in order to meet

citizen needs

·

Developing an offer for citizens and businesses

that they will engage with

·

Establishing a clear set of brand values for

that offer - a set of underpinning statements that adequately describe what the

product or service will deliver and how

·

Delivering that offer though appropriate

channels, in a way which fully delivers on the brand values

·

Generating awareness about the offer

·

Creating desire/demand for the offer

·

Reminding people

·

Changing the offer in the light of experience

This is the process that a brand-led

consumer product company such as Proctor and Gamble or Virgin would go through

when developing a new product. However, it is not typically how governments

manage their own service development, and governments generally lack the skills

to do it. Moreover, the challenge faced by governments is significantly more

complex than any private sector company, given the greater range and complexity

of services and governments need to provide a universal service rather than

pick and choose its customers. Yet if governments are to succeed in the

ambition of shifting service delivery decisively away from traditional channels

to lower-cost digital channels, then these marketing challenges have to be met.

And given the fact that a) citizen needs

cut across organisational boundaries in government and b) the skills for

delivering an effective brand-led marketing approach to service transformation

will inevitably be in short supply, it is important that these challenges are

addressed at a government-wide level.

A TGF-conformant Transformation Program

will establish government-wide processes for managing the three core elements

of the TGF Brand-led Service Delivery Framework illustrated below:

Figure 18: Brand-led Service Delivery Framework

·

Citizen insight

·

Brand-led product management

·

Marketing communications

Citizen insight must inform all aspects of

the process, and involves a comprehensive programme of qualitative and

quantitative research to understand and segment the customer base for

government services. The learnings from this need to be fed into a brand-led product

management process - not as a one-off input of initial research, but through a

continuous process of iterative design and customer testing. A key output from

this will be a set of brand values for the service, which then need to drive

all aspects of service delivery, and marketing communications for the service.

This is an iterative process of continuous

improvement, not a linear one. Continuous citizen insight research is needed to

ensure that both the service delivery experience and the marcoms activity

remain aligned with the brand values, through successive phases of release

deployment. As the service is implemented, across a range of channels, best

practice management information systems can be deployed to ensure that the

Government now has real-time, event-level management information about the

experience of all customers - which in turn provides a powerful feedback loop

into further innovation in the service design.

Often, this will require the Government to

bring in specialist resources, because typically it may face significant gaps

in terms of the people and skills needed to manage brand-led product

development and marketing cycles of this nature.

Identity management is a key enabler, yet

something with which most governments struggle. At the heart of that struggle

is often a failure to put the citizen at the centre of government's thinking

about identity.

A wide range of agencies, standards bodies

and advocacy groups are deeply involved in many aspects of this work, from technical

models for privacy management (such as the OASIS PMRM technical committee) through to the

business, legal and social issues around online identity assurance (such as

promoted by Open Identity Exchange, OIX). It is not the purpose of the Transformational Government

Framework to address the details of identity management or recommend specific

policies or approaches but rather to give high-level guidance on the main

issues that a conformant program should seek to address.

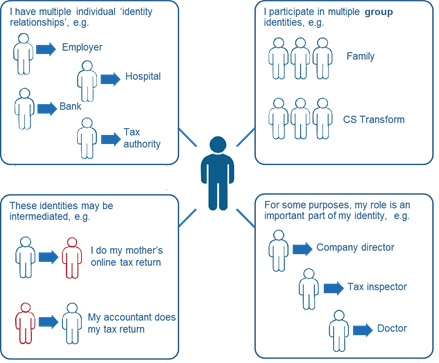

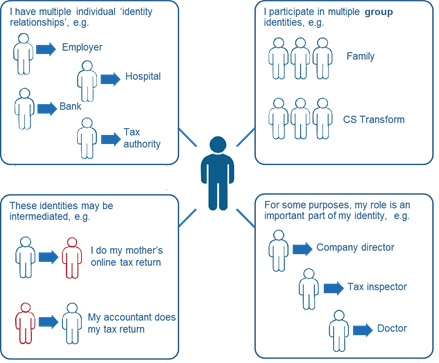

Identity is a complex, and by definition

deeply personal, concept. As the following figure illustrates, a single citizen

in fact has multiple, overlapping "identities".

Figure 19: Complexity of identities

Each identity may be associated with

different rights and permissions, even different addresses. These identities

overlap, but in some cases the citizen may want to keep them separate in order

to protect his or her privacy. At other times, the citizen may want them to be

joined up, and be frustrated at constantly having to furnish government with

the same information over and over again.

Governments have often struggled to manage

this complexity. Typically, identity is defined separately in relation to each

silo-based government service. Even countries which have traditionally had the

simplicity of a single citizen identifier (such as Finland, where there has

been a single population register since 1634), have tended to build up separate

and inconsistent business processes for identity verification. Although the

advent of e‑Government held out the promise of significant simplification

of identity management - bringing service improvement gains for the citizen and

efficiency savings for the Government - significant barriers remain. These

include legal barriers that have grown up over centuries of piecemeal

approaches taken by public administrations (as well as, more recently, also by

the private sector) and put in place often to protect individuals from the

effects of equally piecemeal processes. As such the impact of any changes must

be considered very carefully.

Many of the tools which governments have

put in place to guarantee security in the online world (passwords, PINs,

digital signatures etc), have in practice acted as barriers to take-up of

online services. And attempts to join up databases to enable cross-government

efficiencies and service improvements have often been met with mistrust and

suspicion by citizens.

Increasingly, however, a set of best

practices is emerging around the world which we believe represents a way

forward for citizen service transformation, which is broadly applicable across

a very wide range of governments.

Key aspects of this are:

Firstly, a business architecture for

identity management which is based on federation between a wide range of

trusted organisations (the Government, banks, employers etc), and a clear model

for cross-trust between these organisations.

Secondly, a technology architecture to

support this which does not rely on monolithic and potentially vulnerable large

databases, but which, in line with the SOA paradigm, uses Internet-based

gateway services to act as a broker between the different databases and IT

systems of participants in the federated trust model.

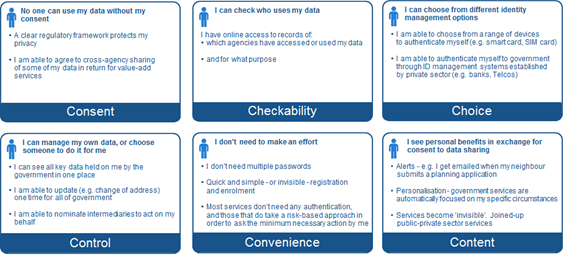

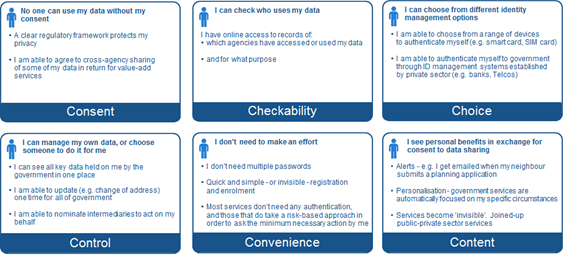

Thirdly - and perhaps most importantly - a

citizen service model for identity management which places citizens themselves

directly in control of their own data, able to manage their own relationship

with government – whether on their own behalf as citizens or in another